What is Verdigris?

It’s funny when a color won’t stay one color.

Verdigris was the first green my group, Team Green, chose to make for our pigment-making project. Not for no reason: verdigris is incredibly beautiful, and before the 19th century, was the most vibrant green available!¹ So, we had a lot to research from verdigris’ long history before we tried to make it. What we found was more surprising–and less green–than we anticipated.

Verdigris is a synthetic, vibrant turquoise-green made by corroding copper through exposure to acid and air over time, a process known as oxidation (think the Statue of Liberty on acid–literally). Though beautiful and bright, verdigris can be difficult to find on manuscripts today due to one unique property: it can change color over time.

A Rainbow of Verdigris

In the first month or so after application, verdigris darkens from a blue-green to green. After this, under certain conditions, the corrosivity of the oxidized copper can degrade the surface or turn it brown over time. Researchers are still not entirely sure why this happens, as this process has yet to be studied closely. It may be due to environmental conditions, such as levels of illumination.² Here is an example of corroded brown verdigris from a 12th-century manuscript:

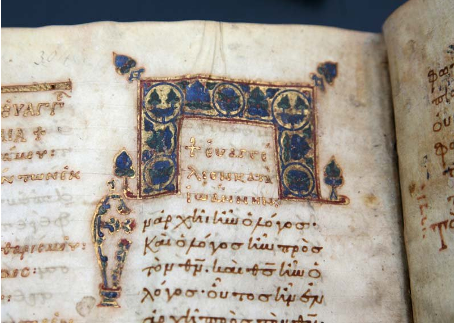

The temperamental nature of verdigris is what sets it apart from other medieval greens. Medieval illuminators were very aware of this: treatises of the time warn against mixing verdigris with other pigments because it would tarnish them, or turn them brown, too. According to a treatise by Jehan le Begue from the 15th century, verdigris is “acrid and corrosive, so that it destroys and corrodes other colors if it is put over them.”³ A green strike-through is often visible on the reverse of the page where the pigment has begun to bleed through.⁴ However, untarnished verdigris is still found in manuscripts today. In these cases, illuminators may have made changes to the recipe to stabilize the pigment, like tempering it with the juice of an herb instead of using vinegar. Here is an example of verdigris from the Fitzwilliam Museum that has become flakier over time, but kept its original color.

Our project was constrained to one semester, so there’s no way of knowing how our own verdigris could change in the future–but we witnessed some unexpected color results nonetheless.

The Recipe

Having learned all about it, it was time to make some verdigris. We followed a medieval verdigris recipe found on the Traveling Scriptorium website.

Like a lot of medieval recipes, this one needed some adjusting for our modern context: for example, it recommends that we put the copper and acid in the ground for six months, which would regulate the temperature over a long period of time. However, we elected to skip this step and hoped a week would be enough time to make a modest, but testable, amount of pigment. (Thanks to air conditioning, we don’t have to bury stuff in the ground to keep it at a consistent temperature anymore. Go figure.)

The Process

The basic ingredients for this recipe are copper sheets, vinegar, a lidded jar, and a metal file. On the first day, we got everything in order to begin the oxidation process.

First, we poured a thin vinegar layer into our two glass jars. Next, we placed plastic white lids perforated with small holes at the bottom of each jar. These act as little platforms for the copper sheets. (If the copper was submerged in the vinegar, no verdigris could form from lack of oxygen.)

We divided the three copper sheets between two jars. Because we were curious whether surface texture changes the corrosion of the material, we sanded two of them and placed them in the same jar and left the remaining one unsanded (spoiler: it had no effect). The most important step was sealing the jars to begin the oxidation.

And that was all it took! The next step was to sit back and let the oxidation process do its thing.

One of my teammates took the jars home to babysit them in her apartment. After about a week, the copper strips were almost completely blue-green: verdigris!

The next step was to simply scrape the green off the surface with a file. It took a while to scrape it all off, and each strip yielded less pigment than we expected. But the bright hue of the powder rescued us from real disappointment.

The process was so easy that we repeated it several times with the same result: not a lot of pigment, but all a gorgeous turquoise color. We enjoyed how automatic the process was–we get why it was popular with stressed-out medieval illuminators.

At the end of our several oxidation cycles, we finally had enough verdigris powder to paint with!

To make paint, we added a little scraped verdigris to a few drops of egg glair–a common medieval binder made from whipped and separated egg whites–and mixed them together. We eyeballed the amounts of each to get a paint-like consistency.

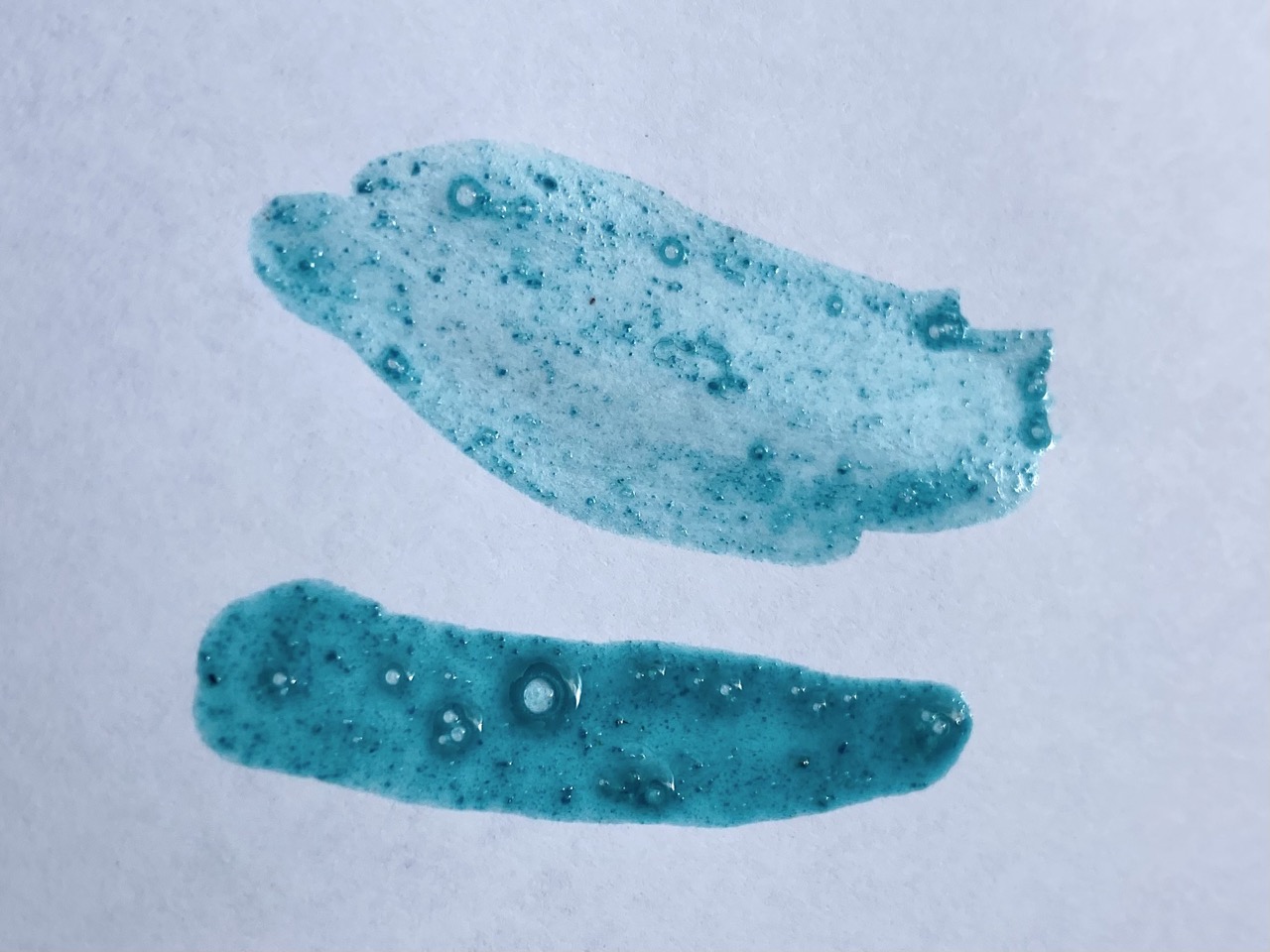

This was when verdigris’ temperamentality showed its face: the color we created was a lot bluer than expected! Because it typically turns greener with time, we expected that the color could start to look a bit more like we expected, but disappointingly, it stayed the same blue the whole class period. Who knew a medieval pigment could be so moody?

Though unexpected in color, our verdigris was still vibrant and beautiful, upholding its claim as ‘the most vibrant green’ of the medieval period. Note how especially glamorous it looks next to the swampy green earth pigment we also made (which you can check out here). Definitely the movie star of the bunch.

Closing Thought on Verdigris

Verdigris was still our easiest pigment to make and produced my personal favorite result–so shiny! The cyclical and almost automatic nature of the process made it enjoyable, and turning the pigment to paint was simple.

The only pitfall in making this color was, well, the color. Despite having all the right ingredients, we still couldn’t get quite the green we expected. We don’t know why this happened, but upon reflection, something we could’ve tried was using egg yolk instead of egg glair as a binder. We suspect the yellow of the yolk could have mixed with the blue hue and made something greener–but our theory sadly remains untested, again due to time constraints. One also has to wonder whether skipping the six-month-burial impacted this unexpected change in results.

But considering everything we know about verdigris, maybe a change in color isn’t so unexpected after all. Its corrosive temperamentality is, as we said, what sets verdigris apart from other medieval greens. We learned more about the pigment by following its color changes than anything else. So, even though our green wasn’t exactly green, we walked away from this experiment having experienced the color-changing star power of verdigris, the medieval mood ring.

Footnotes

¹ Kühn, Hermann. “Verdigris and Copper Resinate” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics (Cambridge University Press: 1986), 132.

² Kühn, Hermann. “Verdigris and Copper Resinate” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, 137.

³ Merrifield, Mary P. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to XVIIIth Centuries on the Arts of Painting, in Oil, Miniature, Mosaic, and on Glass; of Gilding, Dyeing, and the Preparation of Colours and Artificial Gems; Preceded by a General Introduction; with Translations, Prefaces, and Notes. 2 vols. London: J. Murray, 1849.

⁴ Panayotova, Stella, et al. Colour: The Art & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts, Harvey Miller Publishers, 2016.

Works Consulted

Clarke, Mark. The Art of All Colours : Mediaeval Recipe Books for Painters and Illuminators. Archetype Publications, 2001.

Kühn, Hermann. “Verdigris and Copper Resinate” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2. Washington, DC, Cambridge Cambridgeshire: National Gallery of Art ; Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Merrifield, Mary P. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to XVIIIth Centuries on the Arts of Painting, in Oil, Miniature, Mosaic, and on Glass; of Gilding, Dyeing, and the Preparation of Colours and Artificial Gems; Preceded by a General Introduction; with Translations, Prefaces, and Notes. 2 vols. London: J. Murray, 1849.

Panayotova, Stella, et al. Colour: The Art & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts / Edited by Stella Panayotova ; with the Assistance of Deirdre Jackson & Paola Ricciardi. Edited by Stella Panayotova et al., Harvey Miller Publishers, 2016

“Verdigris.” Pigments through the Ages – Overview – Verdigris, http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/verdigris.html.

“Verdigris.” Traveling Scriptorium, https://travelingscriptorium.com/2013/01/17/verdigris/.

Credits

Authors: Charlsie Wemple and Maggie Yarbrough

Featured Image: strokes of Team Green’s verdigris on paper