It’s funny how the earth never opens up and swallows you when you want it to.

Xander Harris, Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Nothing says “Hello, Hellmouth” like a trip to Sunnydale in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Joss Whedon’s beloved television series sees teen Buffy navigating two kinds of worlds: the “real” one we all know and the supernatural one, both full of their own special monsters. Sunnydale sits on a Hellmouth, a hotspot of demonic activity, which is to blame for all that goes bump in the night (and the day and every plane of existence in between). While the term “Hellmouth” has been popularized largely thanks to Whedon, he is not the only one to use it. Activision’s video game, Destiny, has a Hellmouth on the Moon, where an insect-like enemy called the Hive threatens the human race of the future.

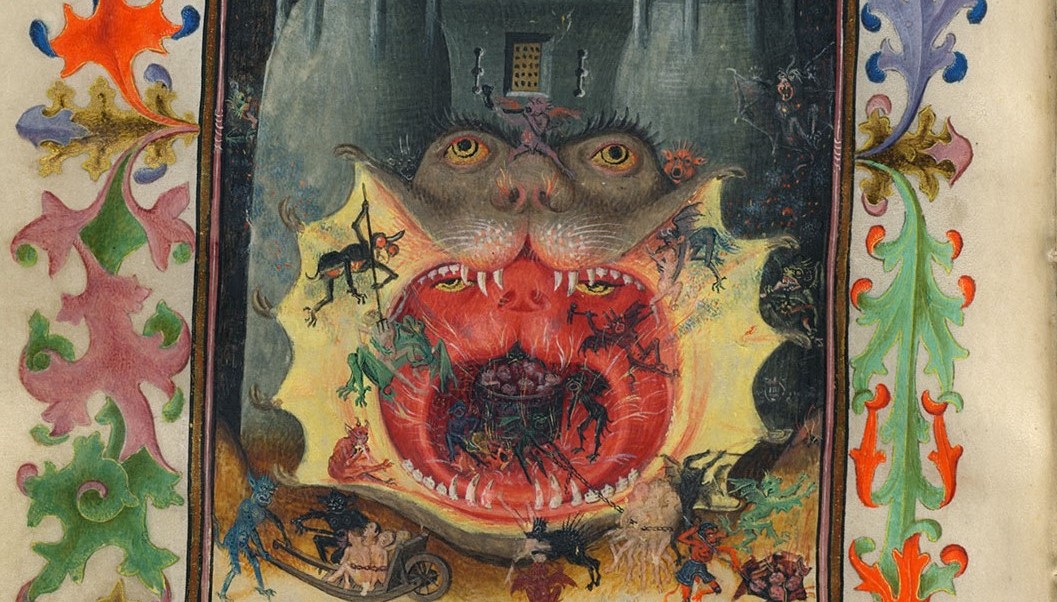

Interestingly enough, these two very different entertainment media utilize a similar idea: an inimical force that opposes the human race from within the earth. Buffy’s Hellmouth connects to the surface via the sewer systems under the city. Destiny’s is a an actual hole in the surface of the Moon. Buffy and Destiny depict the literal Hellmouth, meaning that they do not try to obscure their function as physical connections to a hellscape setting. To connect to the course, Buffy and Destiny depict the physical Hellmouth that medieval Books of Hours do all the time. Just to get a sneak peek of what’s to come, take a look at this beauty! Doesn’t it have some nice pearly whites?

Medieval Hellmouth 1. Cropped image of MS M.917/945, p. 180–f. 97r in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. Cropped to show Hellmouth only.

While using the literal Hellmouth is a common trope in science fiction and fantasy entertainment (as indicated by Buffy and Destiny), there are some entertainment media that employ the Hellmouth in unexpected, unique ways. One of the most influential stories of our age, The Lord of the Rings is not a place you’d expect a Hellmouth to crop up. After all, J.R.R. Tolkien did not call anything a “Hellmouth.” The final book of the trilogy, The Return of the King, however, has one scene in “The Passing of the Grey Company” that does indicate the presence of a Hellmouth. Tolkien was a medievalist and a Roman Catholic, and most of his creative work stems from his time as a professor at Oxford, where he taught medieval languages and literature (Chance 2, 4). He was probably aware of the idea of the Hellmouth, although I cannot say for sure, but he appears to veil it within a cave in the mountain Dwimorberg, where hostile Oathbreakers are bound by broken promises. At the core of this plot point, there is something sinister hiding beneath the earth.

Whether it is explicitly called “Hellmouth,” as in Buffy or Destiny, or is suggested to be a kind of hell, as in The Return of the King, there is a foundational idea connected between the three. Why does this idea of an underground, evil place for the condemned sound so familiar? Where did it come from? Helpful hint: look closer at the name “Hellmouth.”

Textual Depictions of Hell

Some biblical verses indicate that hell is a physical place; they describe it as a “fiery lake” (Revelation 19:20, 20:13-14, 21:8) or a “realm of the dead” (Psalm 9:17; Acts 2:27; Proverbs 15:24). It is designed for the punishment of sins, and it functions as a (physically and morbidly) dark deterrent of immoral behavior (an understatement when we actually see what these places supposedly looked like).

The deep-rooted fear of eternal damnation was prevalent within the religious thoughts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Bernstein, The Formation of Hell 84), and it is a fear that continues well into this day for many people, myself included. This was also the case for medieval persons, who clung to the Office of the Dead in their Books of Hours. There is a fascination with what occurs in the afterlife, and journeys into the hellscape are attempts to understand the afterlife within narrative settings. Alan Bernstein describes the ability to physically descend into and ascend out of a hellscape as the “porous death” (The Formation of Hell 84). We see this clearly in Buffy, Destiny, and sometimes in The Lord of the Rings. It’s not a clear cut-and-dry separation of the living and the dead in these cases, but the dead cannot come back to the surface and the living cannot stay long in the harsh environment of the underworld.

This is where Jesus comes in for Christians. After his Passion and death, Jesus descends into the underworld to release souls and bring an end to sin. There is an important distinction, however, that we must consider. Jesus does not go to hell but to the “neutral underworld” (Bernstein, Hell and Its Rivals 14; Nixon), to release just souls. These just souls are the persons who died before Jesus’ sacrifice and who went into a kind of limbo while waiting for salvation. Purgatory is hell with an expiration date; souls who go to Purgatory are those who died after Jesus’ Crucifixion but need purification before they can enter Heaven. Souls in hell proper, however, are damned for all eternity, and these souls were persons so evil in life, they have no chance for redemption.

Textual depictions of hell appear to have inspired medieval illuminators, who included the Hellmouth in their manuscripts. Now that we understand hell’s physicality, we now can look all the pleasant images of what the average medieval person thought hell to be.

The Medieval Hellmouth

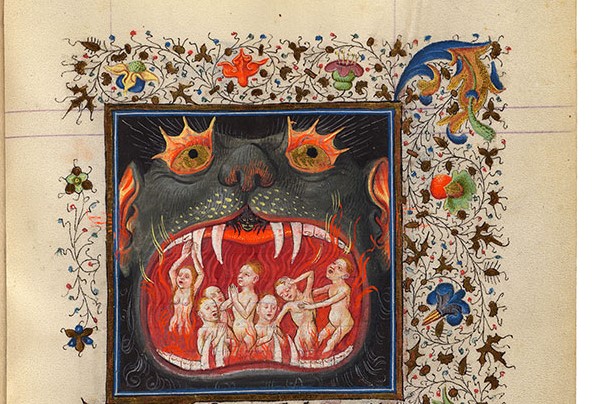

Medieval Hellmouth 2: Cropped image of ff. 168v-189r in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. Cropped to show fol. 168v only.

In medieval depictions of hell, the Hellmouth is a literal mouth, gaping jaws and pointy teeth and all. They appeared throughout the Middle Ages, and their detail is “more imaginative and wonderfully gruesome in their decoration” (Ray). And boy, do they deliver. In Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.917/945 (also known as The Hours of Catherine of Cleves), a manuscript produced in the 1440s, there are three impressive Hellmouths. Demons drag naked souls towards the Hellmouths in chains and wheelbarrows — certainly not a pleasant vacation spot. The outer Hellmouth in the forefront is actually sucking the demons and souls into an inner Hellmouth (Hellmouth-ception), and in the darkest center at the back of the inner one’s throat, there are souls huddled together in a cauldron. We see in vivid detail the fires and darkness here and a formidable fortress behind the first/second Hellmouths’ heads.

This full-page illumination on fol. 168v opens the Office of the Dead, which was used to help reduce one’s time in Purgatory (Raymond and Clemens 217). After looking at some of these Hellmouths, it was understandable why Catherine of Cleves was so worried. This illumination’s placement at the front of the Office suggests that she reflected on the Hellmouth as a very scary encouragement to pray for those trapped in Purgatory (Nixon). On a serious note, it is a frightening image, and to imagine a loved one in a situation like this, where he or she is being tortured even for a small amount of time, is a devastating and crippling thought. This probably incentivized Catherine and other users of Books of Hours to pray fervently for their loved ones (for more interesting information on the Office of the Dead, see Lucas Vaughn’s post).

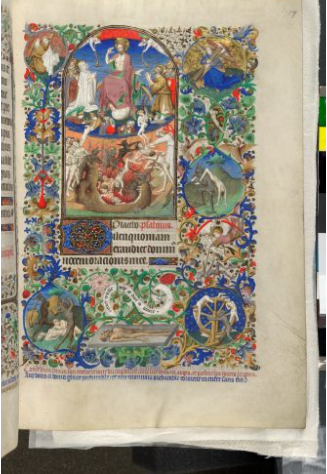

Medieval Hellmouth 3: British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 157r.

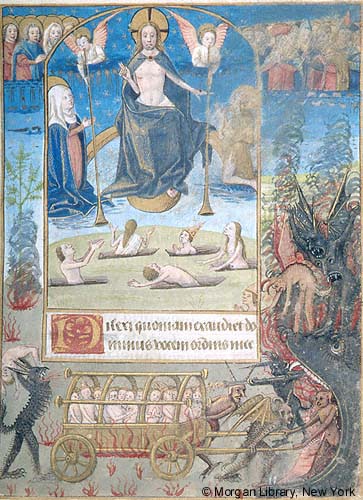

Another couple of medieval images show the Hellmouth: one from Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.1001, which was illuminated in 1475, and a second from British Library, Add. MS 18850 (the Bedford Hours), which was illuminated between 1410-1430. This means they were produced within fifty years either way of the Catherine of Cleves Hellmouth, again hinting at that deep-rooted fear of punishment in the afterlife.

MS M.1001’s and Add MS 18850’s Hellmouths show the two-pronged purpose of these illuminations: “to glorify Paradise and gore-ify Hell” (Ray). This helpful little rhyme explains the two-pronged purpose well; if hell is so bad, you better hope you’re getting into heaven. Jesus, at the top of both of them, resurrects the souls of the just while the demons literally cart or drag the damned to their eternal punishment. And a bit of a discouraging observation on my part, there are more souls going to hell than rising up to Heaven, a clear bid to make one think about the afterlife.

Medieval Hellmouth 4: Morgan Library & Museum, MS. M.1001, fol. 109r.

Unlike Catherine of Cleves’ Hellmouth and Add MS 18850, Morgan Library MS M.1001’s looks more like a cave because of its orientation from the side. We cannot see the inside, which leaves it up to the imagination to wonder what kind of horror awaits in the belly of the beast. In Catherine’s Hellmouth, we look straight down the throat of the monster, so we’re aware that it is some kind of animal. This also allows for the drama of the two Hellmouths and for the final goodbye to the damned burning away in the cauldron. In MS M.1001, the imagination can run rampant, which in some ways is more horrifyingly impactful on people who see the image because we are allowed to come up for worse tortures for the damned than the illuminator. From looking at MS M. 1001, we can see how the physical landscape of a cave-like place plays an important role in our modern depictions of hell; we’ve never truly shaken off the fear of deep, dark places below the earth, which makes them perfect for unfathomable danger and punishment. Inspired by the Hellmouth, modern authors utilize the idea of it to make their settings scarier, realer, and darker. At this point, I can turn to analyzing how depictions of the medieval Hellmouth influences have influenced J.R.R. Tolkien.

The Hellmouth of Middle-Earth

I live and breathe for finding ways that history and ancient fiction have influenced our writings today. I share this enjoyment of the past with other modern authors. These authors, too, look to the past to root their adventures in mythology and believability, and in many ways, apply the mythology of this world to their own universes. We see this clearly in Tolkien’s trilogy. Aragorn’s descent into the hellscape of the Haunted Mountain is actually prophesied by Malbeth the Seer (Tolkien, The Return of the King 54), much like Jesus’ own Passion and death is prophesied in the Old Testament.

To give a brief overview of the plot, Tolkien takes similar ideas of Christ’s Harrowing of Hell: Aragorn descends into the cave, calls forth the dead, and leads them out of the Dwimorberg, the Haunted Mountain. He gives the Oathbreakers a second chance to fulfill their oaths to fight alongside Gondor against Sauron, and once they have done so, he releases them from their eternal punishment inflicted by Isildur (Tolkien, The Return of the King 153). Isildur was a King of Gondor and Aragorn’s ancestor, so via bloodline, Aragorn is able to command and release the Oathbreakers from their curse. It was this plotline that made me realize that Middle-Earth has its own Hellmouth, although it is not as blatantly obvious as the ones in Buffy and Destiny.

The eternal punishment that the Oathbreakers experience correlates to a “purgatorial wasteland” (Sinex 159); they have a chance to be saved, but their separation from peace in the afterlife is enough to be a punishment in itself. It is only through a Christological king and judge, Aragorn, that they can find peace (Padley and Padley 87). Tolkien even describes the cave itself in Hellmouth-like imagery:

The horses would not pass the threatening stone, until the riders dismounted and led them about. And so they came at last deep into the glen; and there stood a sheer wall of rock, and in the wall the Dark Door gaped before them like the mouth of night.

The Return of the King 59; my emphasis

Because it is a “Dark Door,” the entrance to the Paths of the Dead requires there to be a separation between the living and the dead while allowing for the porous death (Bernstein, The Formation of Hell 84). “Night” also roughly equates to the endless sleep of “Death,” again echoing the idea of the “realm of the dead.” And, of course, there is the most obvious connection to the Hellmouth: “the mouth of night.” There is a lot of fear and dread within the language of this description, and the reactions of the men and animals to the cave entrance reflects the same fear of the afterlife that pervades medieval thinking.

IMDb. “Image 224 of 324. Viggo Mortensen in The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003).”

The medieval had a profound impact on Tolkien. In regards to the Oathbreakers, he appears to be influenced by the twelfth-century Latin narrative of the Exercitus mortuorum, or the Armies of the Dead, who wander aimlessly in the hopes of salvation (Sinex 156). While the Oathbreakers do not wander far outside of the cave, they roam through time, banished from rest until a prophesied savior rescues them. This correlates more to the idea of souls trapped in Purgatory, depicted in MS M.1001 and Add MS 18850, rather than the idea of the damned souls being permanently punished in hell. The Oathbreakers, as an Exercitus mortuorum, have potential for redemption, just like the souls in Purgatory that Catherine of Cleves prays for in her Office of the Dead.

Because the Oathbreakers are mostly confined to an underground space, they dwell within a Hellmouth. Rather than thinking of the cave as being a mini-Hellmouth or an incidental underground trapping, I believe that the plot about the Oathbreakers indicates that this is an actual Hellmouth. Roughly analogous to sin, the promise to fight alongside Gondor was broken, and the Men of the Mountain actually are worshipping Sauron. When Isildur confronts them and sees that they refuse to fulfill their oaths, he curses them, and out of fear, the Men flee and do not come to the aid of Sauron during the first war against him. These Men fall to the temptations of a Dark Lord, a devil-like entity who leads them astray. They certainly don’t appear to be evil people, and they are reminiscent of ordinary people who cave into sin. Their ultimate removal from their imprisonment by Aragorn, the prophesied savior figure, also lends to the idea that they are in a purgatorial Hellmouth.

The one key difference between the story of the Oathbreakers and those trapped in Purgatory is that the Oathbreakers, in order to prove their loyalty to Gondor, must fight again. The souls in Purgatory are trapped there (hurried out by prayers from the Office of the Dead) until Jesus calls them out. I suppose in a similar way, souls in Purgatory and the Oathbreakers have to be kindled in the fires of a crucible in order to prove themselves worthy of the compassion of their respective King.

There is undoubtedly an influence of the old on the new; we see it everywhere. Biblical narratives, such as the Passion and Resurrection, live on well into the stories that we have today, and the primeval fear of death and the unknown is something we will never fully reconcile, simply because we don’t know what lies on the other side of it. We’d like to think that there is something good waiting for us after death, but if there is the chance for evil, we feel trapped in, as if we ourselves are in a cave. Still, we have hope, and like the light of Eärendil, “It will shine still brighter when night is about [us]… a light to [us] in dark places, when all other lights go out” (Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring 393).

IMDb. “Image 235 of 324. Viggo Mortensen in The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003).”

Works Cited

Bernstein, Alan E. Hell and Its Rivals: Death and Retribution among Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Early Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 2017.

–. The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian Worlds. Cornell University Press, 1993.

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Cornell University Press, 2007.

Destiny. Console version, Activision, 2014.

Nixon, J. Peter. “Visions of hell: Depictions of hell in art.” U.S. Catholic, vol. 76, no. 11, Nov. 2011, U.S. Catholic, uscatholic.org/culture/art-and-reviews/2011/10/visions-hell-depictions-hell-art. Accessed 8 December 2018.

Padley, Jonathan and Kenneth Padley. “‘From Mirrored Truth the Likeness of the True’: J.R.R. Tolkien and Reflections of Jesus Christ in Middle-Earth.” English, vol. 59, no. 224, Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 70-92. doi:10.1093/english/efp032. Accessed 9 December 2018.

Ray, Alison. “Highway to Hell.” British Library, 18 October 2017, The British Library Board, blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2017/10/highway-to-hell.html. Accessed 8 December 2018.

Sinex, Margaret A. “‘Oathbreakers, why have ye come?’ Tolkien’s ‘Passing of the Grey Company’ and the twelfth-century Exercitus mortuorum.” Tolkien the Medievalist, ed. Jane Chance, Routledge, 2003, pp. 155-168.

“Teacher’s Pet.” Buffy the Vampire Slayer, season 1, episode 4, Twentieth Century Fox, 24 March 1997.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellow of the Ring. 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, 1993.

–. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, 1993.