In the early 1980s, a group of sociologists at Mines ParisTech developed a new approach to their field. They sought, simply, to account for those pesky inanimate objects that sociology had long ignored. Actor-Network Theory posited that “social ties” between people were not a self-sufficient force in maintaining our social fabrics. As Bruno Latour, one of ANT’s founders, explains, “social ties” can only exist in real-world interactions between people—people who are invariably using some kind of object—clothes, telephones, maps (Latour, pp. 64-65). “Groups are made, agencies are explored, and objects play a role” (Latour, 87). Objects have agency too.

ANT set the foundation for a veritable wave of socio-cartographic inquiry in the early aughts. In 2005, Barry Brown and Eric Laurier published one such study. They find that map consultation, in these situations, becomes a locus for the socialized organization of the entire trip. For example, the passenger with the map might say to the driver, “We could check out the Museum dedicated to the history of corn one block down, or we could go to this cool old pub that’s 30 minutes out of the way.” Here, the map-holder is invoking a host of social dynamics far beyond describing spatial relations; she calls on preference, divisions of labor and the hierarchies therein, negotiations of the future. Or, at a red light, by saying “Killin was…” and then pointing to a place on the map already passed, she combines bodily gesture with signification of map-object to fill in for speech while offering the driver a space to respond. This, the authors argue, is but one way that map consultation can be “bound up with the ongoing maintenance of friendship,” among a host of other social ties (Brown and Laurier, p. 27).

Brown and Laurier’s article gave me the framework to understand 43’s remediation of maps in a more complete way. I could see more clearly the social relationship between me, 43, and Robin Price: map reader, map, and cartographer, respectively. My initial experience of performing 43—the way it subverted my expectations and prompted me to seek out all of its nooks and crannies—was a valid effect of this artists’ book’s innate materiality. The socialized relationship between artist and reader—my faith in a deeper meaning to be uncovered—was as much a part of how 43 functioned as the map forms printed on its (one, very long) page. And by incorporating the tactility of maps—the ways they lay and spring, the ways they can be unfolded—she further defamiliarizes the book form. These features forced me to reconsider what I do with my hands as I read even the most typical paperback—what my expectations are as I turn their pages. In these ways, 43 prompts its readers to answer de Certeau’s call: to investigate those mundane, unconscious actions for a deeper meaning.

And I would be remiss to ignore the social structures that brought me to this book in the first place; I am pursuing a graduate degree at a state school so that I can secure a financially, socially, and intellectually rewarding career. It was all of this that pointed me toward what I am exploring now. All of this that led me to the pièce de résistance of my semester’s research: The Sovereign Map by Christian Jacob.

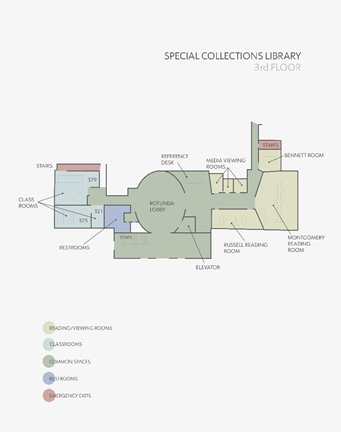

I was equipped with google maps when I started walking south from UGA’s North Campus, which I know like the back of my hand. Having circumnavigated the Main Library’s third floor—realizing there were no “GA” racks—I took a closer look at my screenshot of the shelfmark. “Location: Science 3rd Floor” (emphasis mine). I’d never been to the Science Library. I cut my losses, vaguely anxious about entering this new space. But the Gil-Find summary of The Sovereign Map was too enticing, and with Google Maps to chart the course, the dictates of graduate-level coursework billowing my sails, I set off.

The book is a tome: over 400 pages of “Theoretical Approaches in Cartography throughout History,” as its subtitle promises. There was no way I could read the whole thing on top of all of my other coursework. But—using that nifty little navigational device that we know and love: the table of contents (thanks, early print culture!)—I was able to pick out a few promising chapter titles.

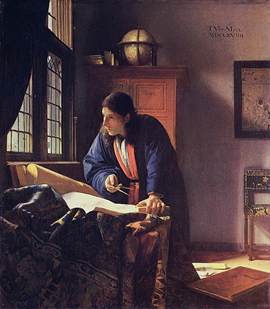

In “The Atlas: A Book of Maps,” Jacob examines this particular genre of book/map synthesis. This is where I was introduced to the concept of the “cartographical gaze,” or the ways that maps control the way we look at them and at the world around us by offering us potent symbolism through their materialized representations. If the world map presents us with a god’s eye view of our environment, but lacks the representative detail of large-scale local maps, then atlases split the difference. These books, indebted to print technology in their accumulation of so many localized maps, form a summative whole that have inspired much imagination and armchair travel.

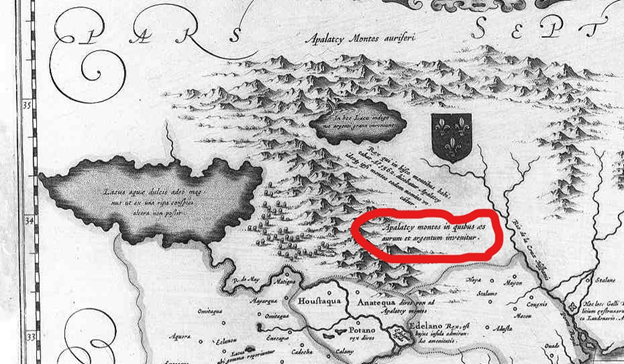

Then, in “The Map and its Legends,” Jacob waxes for 26 pages on this nifty little navigational device. Legends, these days, are those little charts in the corner of maps that indicate which lexicalized concepts a viewer ought to assign to certain shape, colors, or symbols. But this wasn’t always the case. In fact, they originated as syntactical observations in cartographically empty spaces—features like the one indicated in the image above, which, translated from Latin, reads, “Appalachian Mountains in which copper gold and silver can be found.” Their shift, then, to a word-graphic equivalence, as well as to a space outside the map proper (see, again, room-type color coding in Hargrett map below), has had profound effects on the legend’s functionality: its manipulation of the viewer’s cartographic gaze and their reception of the map’s symbolism. In the legend’s transit, it has achieved a greater semblance of cartographic objectivity. It promotes a particular kind of cognitive cross-reference within a single map. In doing so, it prompts the viewer to apply their own understanding of a lexical concept to a stable, material image. This, in the end, is ostensibly less biased than a declarative statement from the mapmaker.

It’s hard not to keep writing about the other theoretical approaches to map-function that Jacob offers. The ways that they shed light on 43’s remediation and functionality. But I’m already close to running long and losing your attention (if I haven’t already), dear reader. Suffice for now that maps are markedly social objects, and they have a complicated history of forms and features that affect how they function in the world.

Click through, at your leisure, to read my final blog post (coming Dec. 6), where I will have space to expand further and you can see exactly why exactly I bring up these two Sovereign Map insights, in particular.

Works Consulted

Brown, Barry and Eric Laurier. “Maps and Journeys: An Ethno-methodological Investigation.”

Cartographica, vol. 40, no. 3, Fall 2005, p. 17-33.

De Certeau, Michel. “Reading as Poaching.” The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven

Randall, University of California Press, 1984, pp. 165-176.

Jacob, Christian. The Sovereign Map. The University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Price, Robin. 43, According to Robin Price, with Annotated Bibliography. 2007. Robin Price. Rare

Books Vault, Special Collections Library, University of Georgia.

Header image: “Maps” opening, showcasing the view of 43‘s bottom-layer accordion that such a position allows