In the past fifty years, my family Bible was not used as a means for reading or studying scripture, but to store family records and recall the names and dates of birth of those who had already passed on. Before venturing into the book with an academic lens, I believed the marriage, birth, and death records to be the product of a handy family member, one who had a knack for jotting down events and keeping written memorabilia. I soon discovered that family Bibles, such as the one in my own family, were much more than a book full of scripture. They were recognized as a place of safekeeping for important and sometimes official records. What began as a form of entertainment when I was a child, sitting at the dining room table with my father and grandmother examining a dusty book, turned into a deep dive in the history of the American family Bible.

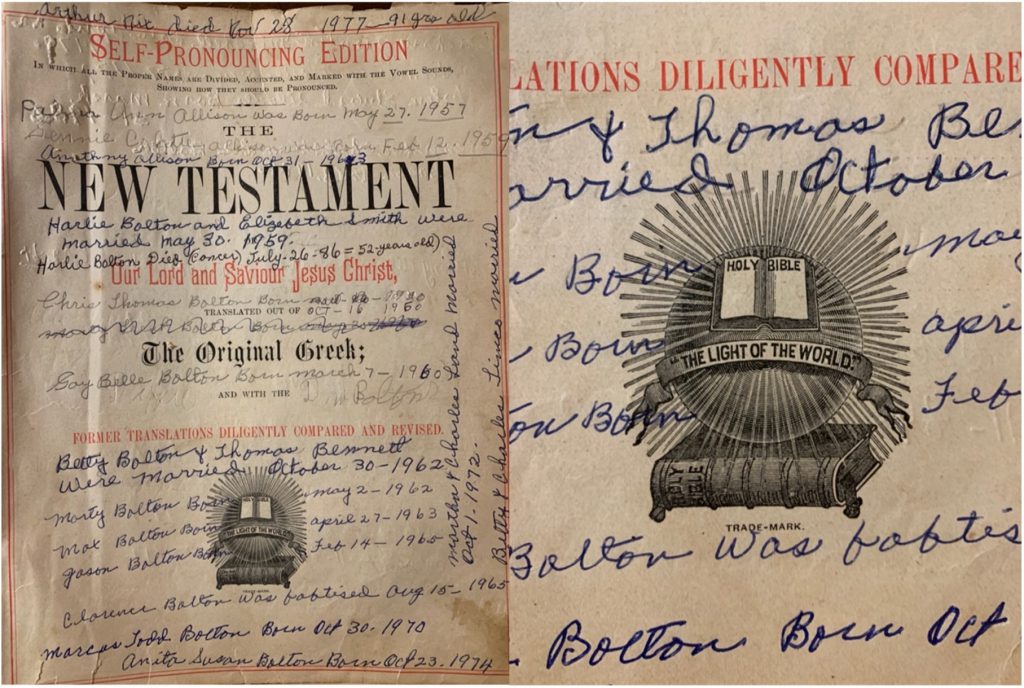

Before I jump ahead of myself, let us walk back to rural Georgia in the late 1800s, specifically to the counties located just north of Atlanta. Unlike our modern system of placing orders through an online server or through a mail-order catalog, many families in rural towns were visited by “a traveling Bible salesman” who offered them the option of Bible customization (Briley 9). Salesmen would offer families different choices in outer properties, including the cover and spine of the Bible, and a variety of inner pages offered by the publisher (Briley 9). These door-to-door Bibles can be denoted by the trademark symbol located on the title pages. The “Light of the World” trademark, as seen on the title page in the family Bible below, marks the book as a Holman Family Bible (Briley 9). Holman Bibles, while ordered through the Bible salesmen, were printed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Briley 9).

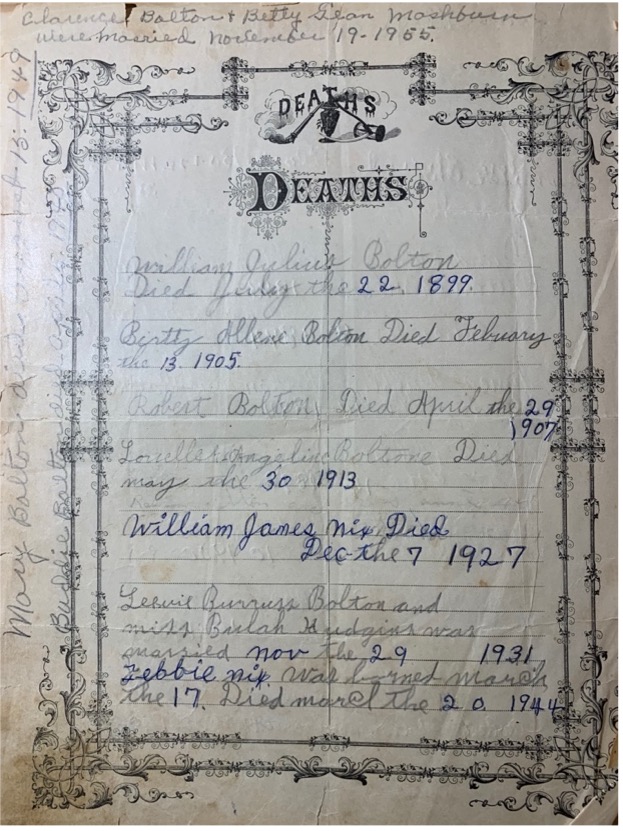

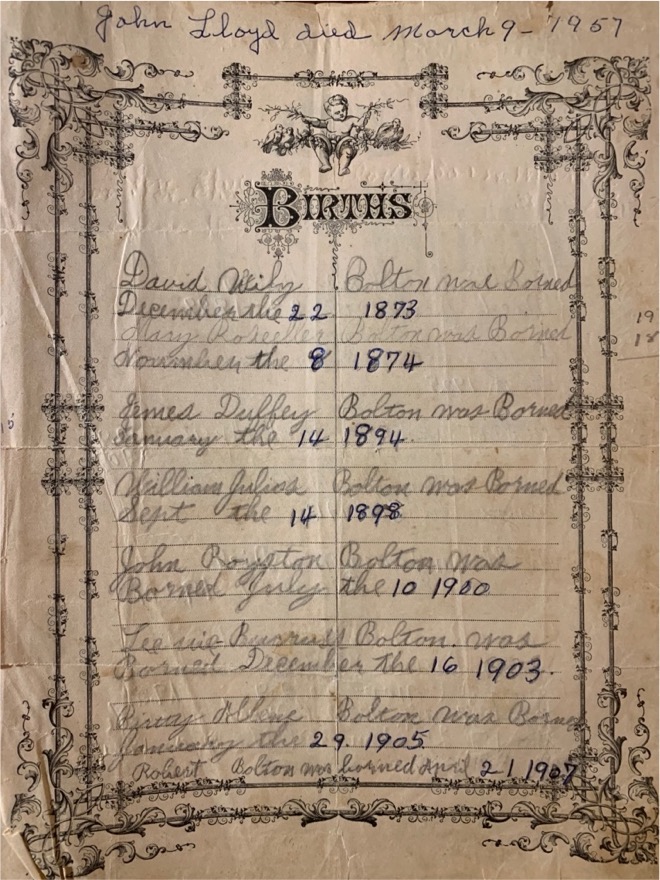

This specific Bible, called “The Old Family Bible” by my relatives, shows its weariness from cover to cover and everywhere in between. Many of the original opening pages are missing, most likely lost between its many owners. In its current condition, the Old Family Bible begins with the Book of Genesis and works its way through the end of the New Testament. In between the Old and New Testament there is a collection of pages with extensive family records. Some pages are structured in the form of birth or marriage records, while others have been transformed from intended title pages to detailed lists of names. These lists compile relatives from the late nineteenth century through the twentieth century. This abundance of written history is where my academic interest in the Bible began to spike.

My grandmother always treated the pages of writing in the Old Family Bible with the utmost care. While it may have been because of the Bible’s age or brittle nature, I now wonder if those in the generation before her knew that the records were significant beyond their direct familial affiliation. In fact, “for most literate Americans during the early nineteenth century, family Bibles were the standard way of keeping a family record” (Landrum 126). While northern states moved in the direction of using birth records as “identity documentation” before southern states, American birth certificates were not used as identification on a large scale until the early twentieth century (Landrum 125). Pages, like those pictured below, were printed into family Bibles from their production. Because these pages were recognized historical documents, family Bibles of this kind were not mere mechanisms for biblical study. These Bibles were also purposed to allow families the ability to create and maintain their own genealogical records.

Continuing forward with my research, I began to wonder about the significance of this recording process and the autonomy that came as a result. This specific Bible, which is established as a “self-pronouncing” edition, places a great deal of authority in the hands of the owner (Self-Pronouncing Bible). Not only is this family Bible structured to prompt its owners to become one of its authors through the written records, but the Bible communicates to readers how its scriptures should be spoken. Also noting the location of the self-pronouncing title is important, as it falls before the beginning of the New Testament. While the New Testament is frequently presented on paper, “These collected writings did not arise as scripture on inked pages…Rather, the contents of the New Testament originated as oral stories” (Rhoads 157). Therefore, because “Bible reading was a daily activity for many families,” the self-pronouncing nature of the Bible accented the authority the household figure had to educate the family through oral practice (“Family Bibles”).

It is difficult to go back in time and picture the Old Family Bible as I once did: a cool book that my grandmother would pull out on special occasions. While I still love gently flipping through the pages and searching up my family history, my mind wanders to new ideas of authority and religious jurisdiction. This Bible calls to a space in time where written documents in a family book could stand alone in court, which is something that is difficult to fathom today. The pages also represent a shift in the old tradition of studying the written word, perhaps prompting readers to engage in oral tradition. Those who purchased it and those who followed the practice of record keeping all placed their faith in a book that would outlive them by years. Maybe they knew it’s not people who live to tell our stories, but the books that live beside us.

References

Briley, Harry. Old Family Bibles. E-book, Livermore Heritage Guild, 2018.

“Family Bibles.” Houston Baptist University, Dec. 2015, https://hbu.edu/museums/dunham-bible-museum/tour-of-the-museum/bible-in-america/family-bibles/.

Landrum, Shane. “From Family Bibles to Birth Certificates: Young People, Proof of Age, and American Political Cultures, 1820–1915.” Age in America: The Colonial Era to the Present, edited by Corinne T. Field, and Nicholas L. Syrett, New York University Press, 2015, 124-147.

Rhoads, David. “Biblical Performance Criticism: Performance as Research.” Oral Tradition, vol. 25, no. 1, Mar. 2010, pp. 157–198.

The Bible. Self-Pronouncing Edition. Light of the World.

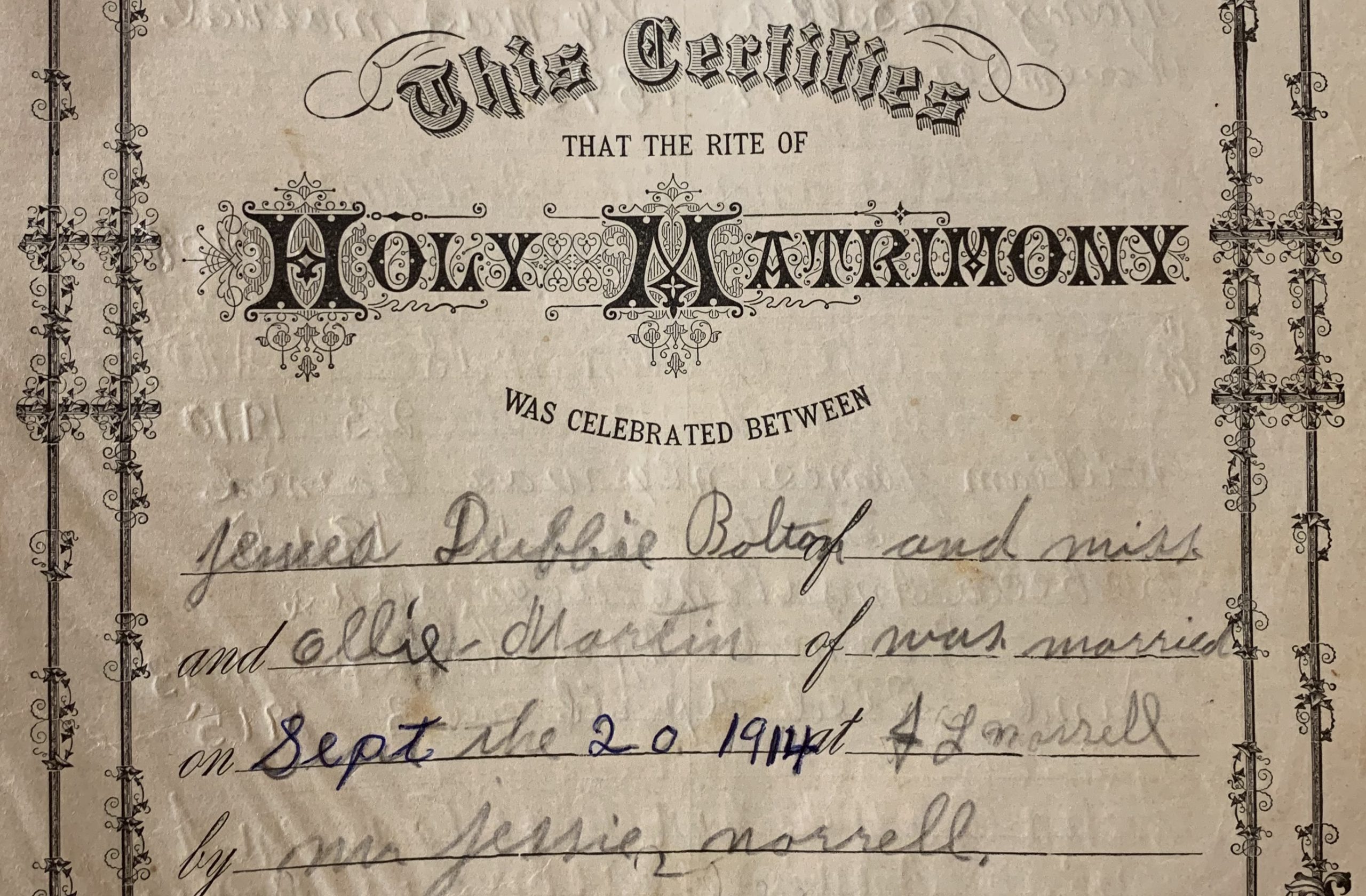

Featured Image: The handwritten marriage record is located between the Old and New Testament in the family Bible. Photo by Lindsey Allison. (The Bible. Self-Pronouncing Edition. Light of the World.)