This post contains images depicting sex and various stages of nudity.

I know I said in the last post that Issue #3 of Wimmen’s Comix #3 has “calls for audience participation, experiments with form, passive-aggressive jabs at other feminist media producers, satire, autobiography, sex, abortion, board games, castration, and even spaceships!”—but in order to fully understand the significance of all that, I should probably start with a brief elaboration on hypermediacy and how that relates to the comics form.

“Hypermediacy” is one of those terms that appears super academic and complicated, but once you hear the definition, you realize you’ve been seeing examples of it for years. In its most basic sense, hypermediacy is when a work of art knowingly calls attention to its own medium—a 4th Wall Break not just as a character, but as parts or even the entire work winking towards the camera. A fun example I grew up with would be this clip from Cartoon Network’s show Chowder, wherein the characters running out of money means they also run out of money for animation. Suddenly the entire presentation of the work changes from vibrant and wacky 2D animation to a live-action scene of the real voice actors sitting in the studio, confused and stressed, before cutting to a scene of them outside starting a car wash to earn cash.

When Dwight Schultz, the voice actor for the character Mung Daal (aka, the blue one), declares that they “have enough money to get the animation back,” the medium switches mid-sentence back to said animation, and the plot of the episode continues on.

As Richard Grusin writes, “In every manifestation, hypermediacy makes us aware of the medium or media and (in sometimes subtle and sometimes obvious ways) reminds us of our desire for immediacy”—in other words, the desire for a sense of unbroken realism within a piece of art (34). The voice actors starting a car wash to “save the show” and return Chowder to its previous animated state dramatizes this desire and underscores how, even when watching an obviously fantastical piece of media, the audience can nevertheless “believe” in the reality of the story being presented, “suspending our disbelief” rather than consciously thinking of the potentially numerous human beings behind its production.

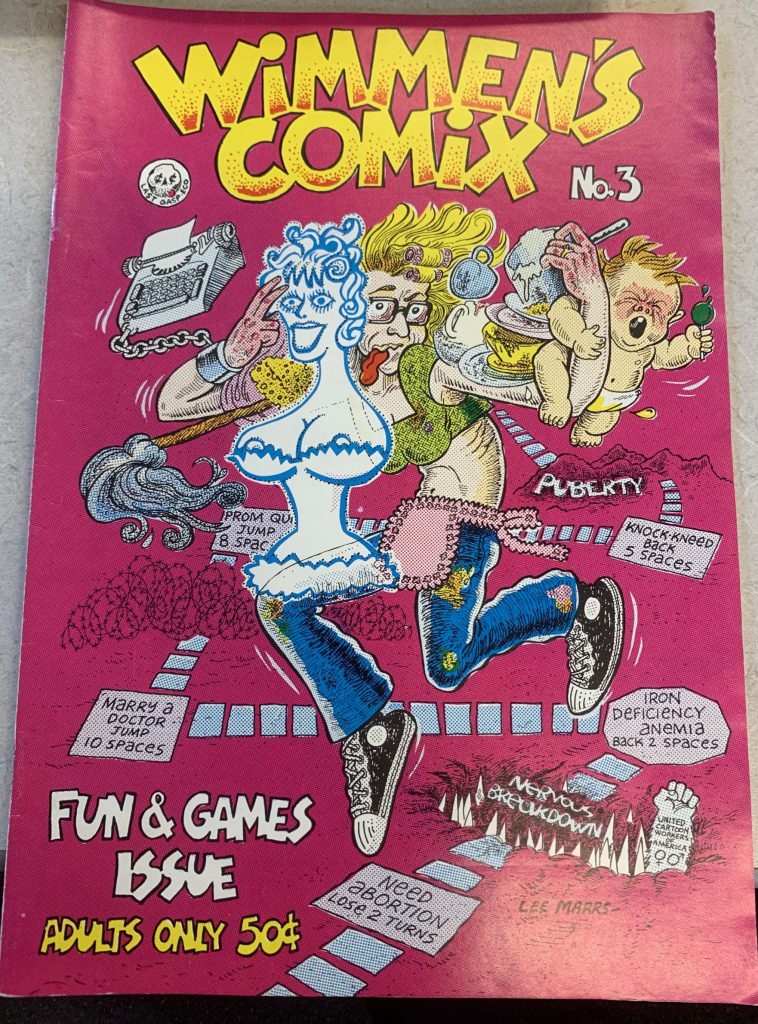

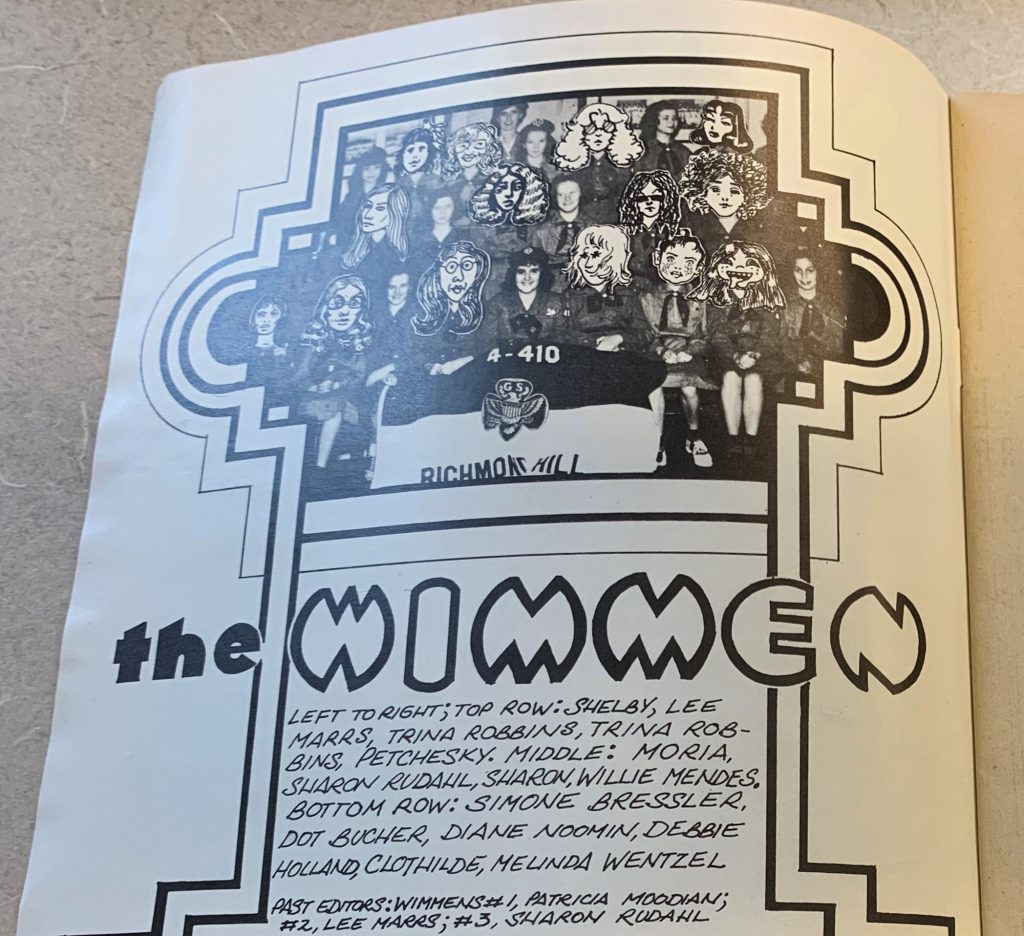

As mentioned in my last post, Wimmen’s Comix #3, the “Fun & Games Issue,” is a 175 mm-by-252 mm anthology comic book published by Last Gasp Eco-funnies in 1973, with 13 contributors dispersed over 16 leaves of thin, black-and-white newspaper. Most issues of Wimmen’s Comix open with a group portrait of the editorial team drawn onto the inside front cover, but in “Fun & Games,” this portrait takes the form of a group photo with each editor’s face drawn over with a self-caricature.

Although the reader can’t fully see the uneven texturing that the original collage-photo would have had, the visual difference gives enough for us to replicate it mentally. Further, the drawing over of faces suggests that these cartoon versions are more representative of this comix’s project than the editors’ real faces.

(Other comics in Issue #3 also utilize the reverse of this technique by pasting photographs into their drawn narratives, although one such example is a pretty graphic surgical castration, so you can thank me for not showing it to you.)

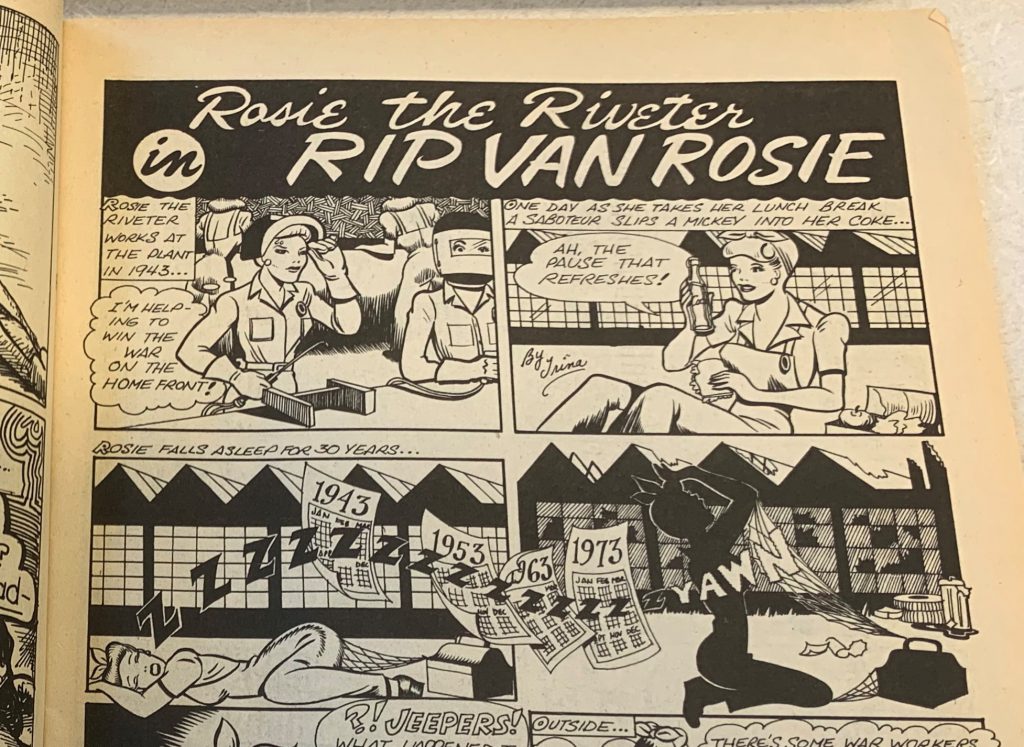

As Hillary Chute points out, “The early newspaper comics [in the United States]. . .were formally experimental” while also fully inhabiting their “popular, reproducible status” (75). Even as far back as the early 1900s, cartoonists such as Winsor McCay, author of Little Nemo in Slumberland, were experimenting with their comics’ panelization. While not every comic in Wimmen’s Comix Issue #3 is obviously experimental and hypermediated, almost every one plays with the form of comics in some manner, particularly through panels. For example, the second comic in Issue #3, “Rosie the Riveter in Rip Van Rosie” by Trina Robbins, manipulates panels to condense Rosie’s 30-year power-nap into only two panels:

Although the first two scenes had been neatly contained by their panels’ borders, suddenly the sleeping Rosie rests half-in and half-out of the third panel, her body dipping into the scene immediately underneath her. Calendar pages fly out of one box-shaped panel and into one without borders at all, signifying the drastic shift in time and—as Rosie and the reader will both soon learn—culture that has taken place between these images.

I titled this post “You Need To Have A 4th Wall to Break It” because, unlike many forms of media, the issues of Wimmen’s Comix don’t have a truly unified logic of “immediacy” or overarching narrative cohesion. Narrative and structural cohesion certainly can exist in individual stories, but the stories are so short you only barely have time to get a feel for their “logic” before it’s already over. Further, even as you’re reading, you’re rarely not catching a glimpse of an entirely different comic in an entirely different art style out of the corner of your eye. Comics, then, force the reader to “keep coming back to the surface” of the page—as Grusin writes, “in the logic of hypermediacy, the artist. . .strives to make the viewer acknowledge the medium as a medium and to delight in that acknowledgment” (41-42).

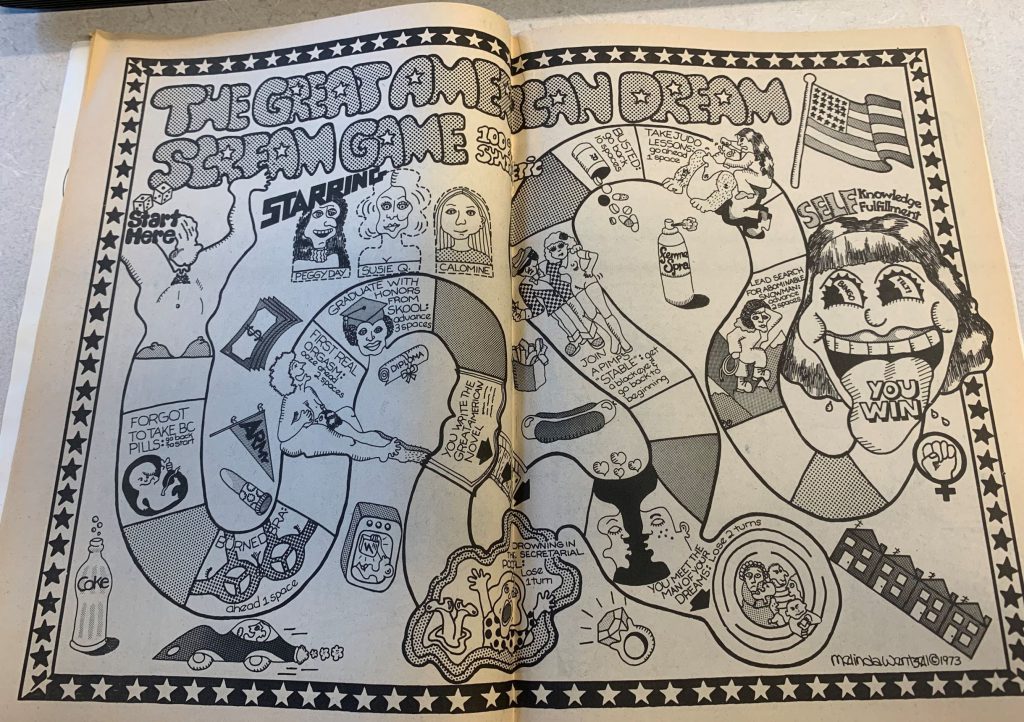

These “delights” take many forms: splash pages that form a satirical board game or pinball machine, requiring the reader to turn the whole book on its side; calls for any male readers to send in pictures of their junk or “match” the sexual preferences listed in the pinball game to their respective editor; and even a feedback form on the inside back cover that asks such irreverent questions as “I am sexually aroused by [ ] middleaged anteaters [ ] vacuum cleaners [ ] large bananas [ ] electric pencil sharpeners” (D.K. Holland & Melinda Wentzell).

You, as an audience member, are never not aware of what you’re reading and that you are reading. The salacious fake ads and contests, constantly changing art styles and layouts, and hybridization of images and words all require constant interpretation. Yet despite the comics’ short lengths, unlike with a traditional text, you can also spend all the time you need on any one panel. If you wanted to, you could even cut out the tiny pieces and try and play Melinda Wentzell’s “The Great American Dream Scream Game” for yourself.

While these fun, form-breaking elements turn real sources of stress and anxiety—such as “drowning in the secretarial whirlpool” or becoming trapped as a housewife—into dark comedy, the inclusion of real photographs further encourages that we re-center our readings in the realities these comix comment on.

So that’s what the comix do, Art TM-wise. How was it received?

As Lee Marrs, a long-standing member of the Wimmen’s Comix editorial team (and the artist behind this issue’s lovely cover) once noted in an interview, not all feminists agreed with the material presented in these comic books. “the women’s movement in the beginning didn’t have any sense of humor in itself, which is sad but typical. [. . .] We got totally rejected by the women’s movement for the most part” (Kirtley 274-275). The “Fun and Games” issue even directly calls out the feminist magazine Ms., criticizing its team for refusing to run Wimmen’s ads while simultaneously employing zero women on their own art team. In the final post, I’ll explore this reaction and dig deeper into how these comix used their production and participatory elements to create their own specific kind of feminism.

*****

Works Cited

Chute, Hillary. “Time, Space, and Picture Writing in Modern Comics.” Disaster Drawn : Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016, pp. 69–110. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=cat06564a&AN=uga.9945894953902959&site=eds-live&custid=uga1.

Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin. Remediation : Understanding New Media. The MIT Press, 1999. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=nlebk&AN=9351&site=eds-live&custid=uga1.

Kirtley, Susan. “‘A Word to You Feminist Women’: The Parallel Legacies of Feminism and Underground Comics.” The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel, edited by Jan Baetens et al., Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 269–85. MLA International Bibliography, EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=mzh&AN=2018050118&site=eds-live&custid=uga1.

Women’s comic book collection, ms4091, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, The University of Georgia Libraries.