by: Tequilla Richardson

Reflective Introduction

Special education is a very broad and diverse field that encompasses teaching for a wide array of disabilities, ranging from physical impairments to neurological disorders. The field of special education has grown tremendously since its initial appearance in 1975, creating room for newly improved teaching techniques to be integrated into the classroom. A more positive attitude has developed towards special education, as many schools now integrate special education students into their general education classrooms (otherwise known as inclusion). Yet, most importantly, special education students have solid protection in place to respect their disabilities and also provide equality amongst other students.

Abstract

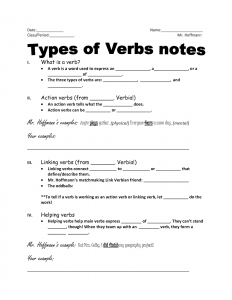

Within this project, I intend to demonstrate that guided notes are an effective method to incorporate into a classroom. I intend to prove myself through consulting various professional journals and research studies, as well as referencing a special education course I excelled during the spring 2016 semester. I found the topic of guided notes interesting because they are such a simple, yet powerful tool. Moreover, guided notes are applicable to all age and grade levels: elementary, middle, and high school. In my opinion, guided notes are so valuable because they can be coupled with other learning techniques within all subjects/topics. Overall, this topic is extremely important and relevant because special education students are often overlooked. In essence, I will present a brief introduction to guided notes followed by tips for appropriate (and successful) usage. To add validity, I have researched several studies conducted within various classrooms further attesting to the effectiveness of guided notes. To conclude, I will include my personal experience with guided notes.

The term special education has come to include hundreds of disorders and disabilities. Through special education services, students now previously overlooked and/or ridiculed have access to equal services and treatment. In the last few decades, there has been a huge push towards incorporating these students into general education classrooms, a move termed inclusion. In an effort to provide equality within inclusive classrooms, more and more teachers are turning to various learning techniques for students. One of the most popular techniques is guided notes; guided notes are handouts provided by a teacher that outline key concepts and information. Guided notes are indeed effective tools to utilize within the classroom because they promote equal access to material while also enhancing student learning by organizing information; in addition, guided notes help further the overall vision of special education by promoting inclusion for both educators and students.

Guided notes are best implemented in traditional classroom settings (i.e. lecture-based). When paired with lectures, guided notes provide students with the most important information, while also retaining their attention. Guided notes leave blank spaces for students to fill in during the lesson’s progression, prompting active student listening/participation (Heward 1). Most importantly, guided notes can be revisited for future studying, a necessity for all students. The basic idea behind guided notes is quality over quantity, helping to prevent students from being overwhelmed with information. All students are provided the same sheet and expected to fill in the same information using sentence clues and other resources such as textbooks, classmates and/or media and video supplements. Guided notes work so well in traditional, inclusive classrooms because no student feels singled out, primarily special education students. If special education students are separated from their general education peers, they can feel discouraged or underappreciated.

When determining how to implement guided notes into a classroom, the most important step is to carefully monitor each student. Educators are responsible for knowing students’ strengths, weaknesses, and any accommodations needed. In order to maintain classroom balance and include all students, guided notes help bring everyone to the same level by providing uniform information. Upon determining the need for guided notes, teachers should choose the most important information from the lesson/text, in order to: prevent overloading students with information, retain students’ attention span (including students with ADD/ADHD), and also choose information that can connect to other topics of the course, either in review or the foreshadowing future lessons. Students learn best when they feel connected to the presented material and see a correlation with the final assessment required at the lesson’s conclusion.

As the lesson progresses, teachers should inform students of their responsibility to actively attend to the lecture and/or video and to fill in information as it arises during class discussion. To make special education students more comfortable, teachers can fill in the note-taking sheet at the same time if needed. If the lecture involves a video or other digital media, the teacher can stop the video when needed to allow students time to fill in their guided notes handout. At the lesson’s conclusion, the teacher can check for students’ completion and accuracy of the handout with an assessment. The most effective assessment is students’ independent practice, which typically occurs as a quiz. Quizzes are a quick way for teachers to evaluate students’ comprehension and see if further alteration of the guided notes handout is needed. Quizzes can come in a written version, oral examination, or as a ticket-out-the-door assignment in which students jot down salient information from the lesson after reading through the guided notes handout and listening during the teacher’s instruction. In part, guided notes are so successful because they are easy to implement and lead into other assignments such as quizzes to verify student comprehension. Their implementation is especially useful within an inclusive classroom because they help teachers to judge their effectiveness based upon assessment performance. Afterwards, the teacher should also allow the opportunity for students to provide feedback for future improvement with a post-assessment. When students feel their input is valued, they are more receptive to their teacher and the presented material.

Guided notes are versatile, meaning they are efficient study tools for all types of students, both disability and non-disability, across all grade levels (elementary, middle, and high). Particularly, guided notes work well with students who have a writing impairment or difficulty focusing their attention during a lecture; however, guided notes can also aid those with a visual and/or hearing impairment. Those with an intellectual disability are particularly receptive to guided notes because these supports help with metacognition and organization. Within his Ohio State University fast facts sheet, William Heward notes, “The listening, language, and/or motor skill deficits of some students with disabilities make it difficult for them to identify important lecture content and write it down correctly and quickly enough during a lecture. While writing one concept in his notebook, the student with learning disabilities might miss the next two points” (Hughes & Suritsky, 1994). Thus, guided notes help supplement students having to write as much information so quickly; virtually, students are not as pressured to write every piece of information and in turn feel more relaxed and engaged with the material. Heward goes on to state: “Course content is often presented via lecture in unorganized and uneven fashion. This makes it difficult for students to determine the most important aspects of the lecture (i.e., What’s going to be on the exam?)” (Heward 2). Through his argument, Heward remarks upon the organized, succinct layout of guided notes.

Several research studies have been conducted to test guided notes’ effectiveness. These studies range in target audience, length, and selected disabilities. One study conducted in an elementary science classroom analyzed the impact of guided notes for three students with intellectual disability and autism. Within “The Additive Effects of Scripted Lessons Plus Guided Notes on Science Quiz Scores of Students with Intellectual Disability and Autism”, Bree A. Jimenez, Ya-yu Lo, and Alicia F. Saunders note:

The Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of 2004 and the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001 emphasized that students with disabilities should have the same opportunities to learn and be held to the high standards as their nondisabled, same-age peers by accessing and participating in the general education curriculum” (231).

The authors’ familiarization with imperative special education legislation adds to the validity of their research on guided notes. The authors revolve their argument in support of guided notes solely because of federally enforced legislation. In the study, the three students were administered three different quizzes (covering three different units) individually by the special education teacher. The special education teacher first began with a traditional lecture format. The same teacher then provided the three students with guided notes. The guided notes served as a reinforcement of important concepts from the lesson, while also allowing all students equal access to the same information. Overall, the three students’ quiz scores improved upon using guided notes. The author’s point is further emphasized: even special education-classified students deserve a fair, equal education and when provided such, can excel at high rates.

Guided notes were also implemented in a high school classroom. In this study, the authors (Karen H. Larwin, Daniel Dawson, Matthew Erickson, and David A. Larwin) also address the relevance of special education legislation in terms of employing guided notes. In “Impact of Guided Notes on Achievement in K-12 and Special Education Students”, they note:

The right to a free, appropriate public education (FAPE) and an education in the least restrictive environment (LRE) are two of six guiding principles of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that drive special education practice. Implicit in these principles is the right of all students with disabilities, regardless of their severity, to have an opportunity for meaningful access to the general education curriculum (Wood, 2005, p.7) (K. Larwin, D. Larwin, Dawson and Erickson 108).

This “opportunity” the authors mention above is fostered by their guided notes research. Essentially, guided notes operate as an attempt “to provide students with disabilities the appropriate accommodations and modifications to the general education curriculum…teachers strive to find resources and supports to help these students be successful” (K. Larwin, D. Larwin, Dawson and Erickson 108). The 26 students in the study are all diagnosed with learning disabilities and/or emotional-behavioral disorders. In the study, the authors conclude that the guided notes benefit all of the students. The authors write, “guided notes in the form of written cues to promote the use of meta-cognitive skills were provided to help students identify lecture topics, link topic to prior learning, summarize, and reflect on key points throughout the lecture” (K. Larwin, D. Larwin, Dawson and Erickson 110). The authors reference Joseph Boyle in maintaining that “teachers can improve note-taking skills of students with mild disabilities by either modifying their presentation during lectures or teaching students how to use note-taking techniques to students” (Boyle 110). They later add, “Students with disabilities are often unable to identify the important information to note; are unable to write fast enough to keep up with the lecturer; and, even when they do record notes, are frequently unable to make sense of their notes after the lecture, mostly because their notes are illegible” (K. Larwin, D. Larwin, Dawson and Erickson 110). If students’ notes are unorganized, they will have difficulty on assessments. The authors again reference Boyle with: “difficulties with note-taking presents a major problem for students’ success in the general education classroom, especially in content area classes, where instructors often use their notes to develop tests, which in turn serves as the basis for grades” (Boyle 110). Reverting back to earlier ideas, guided notes helped these students to retain information learned and also practice their note-taking for successful test performance. Overall, the 26 students in this experimental group saw significant improvements in their testing, as opposed to the students who did not participate in the research study (whom were given free range in their note-taking).

In another case, guided notes were used within a collegiate classroom. In the study, “Effects of Guided Notes on Enhancing College Students’ Lecture Note-Taking Quality and Learning Performance”, the authors (Pin Chen, Timothy Teo, and Mingming Zhou) note, “According to Peper and Mayer (1986), the process of taking note helps make students’ attention more selective, forces students to organize ideas, and helps them relate material to existing knowledge, thus facilitating learning” (Heward 1) as her reasoning for conducting the guided notes study. In this case, guided notes were used not only as equal-information providers, but also as an incentive for students to practice note-taking. Note-taking is a concept that many students struggle with, which makes guided notes that much more valuable. In his Ohio State University fast facts sheet, William Heward quotes, “Many college students do not know how to take effective notes. Although various strategies and formats for effective notetaking have been identified (e.g., Saski, Swicegood, & Carter, 1983), notetaking is seldom taught to students” (Heward 2). Thus, it is helpful that guided notes are traditionally fill-in-the-blank and encompass the most important pieces of information. When Heward is asked whether guided notes make a college-level course too easy, he responds: “To complete their guided notes students must actively respond—by looking, listening, thinking, and writing about critical content—throughout the lecture. We make it too easy for students when we teach in ways that let them sit passively during class” (Heward 3). Heward’s words help shun skepticism of guided notes by highlighting a significant aspect: guided notes help get students actively connected with classroom material by coercing them to pay attention and actually write down information, as opposed to just sitting and listening to a teacher lecture nonstop. In this, students are not just “spoon-fed” all information and instead, engage in learning discovery by gathering information piece-by-piece. Basically, the college students’ classroom performance improved because the quality of their notes developed rather than the quantity (Chen, Teo and Zhou 2).

Guided notes are so remarkable in my opinion because of my personal experience with them. Although I do not remember having special education students within my classes, I can still attest to the impact guided notes created. For my pupils who had trouble focusing their attention or lagged behind, guided notes provided that cushion of support that they needed. Guided notes are traditionally fill-in-the-blank and cover the most important information of a lecture or video. For students like me, guided notes allow us to remain engaged by filling in information along the way. I have always been the type of student who grasps information quickly and naturally retains information. Still, there were times when I struggled in retaining more difficult concepts and guided notes provided an easy template for me to study. I can remember utilizing guided notes the most within my social studies courses because of the huge range of dates and historical events. In essence, guided notes served as reinforcement for information we already grasped. Thus, having this review better prepped us for quizzes and other forms of assessment, while bringing our classmates up to speed.

In conclusion, guided notes have a very impressive success and approval rate. They are quick, simple tools to integrate into a classroom, as well as any scholastic subject. Guided notes have an important function within all sorts of classroom, but especially within inclusive classrooms. Tons of research is available in support of guided notes because they are used for both general and special education students note-taking. In essence, guided notes are popular because they demonstrate that equal opportunity and performance are crucial indicators of a classroom’s success.

Works Cited

- Chen, Pin-Hwa. “Effects of Guided Notes on Enhancing College Students’ Lecture Note-Taking Quality and Learning Performance.” (2016): n. pag. Web. 6 July 2016. http://link.springer.com.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/article/10.1007%2Fs12144-016-9459-6

- Heward, William L. “Guided Notes: Improving the Effectiveness of Your Lectures.” Ohio State University Fast Facts Sheet (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 11 July 2016. http://ada.osu.edu/resources/fastfacts/Guided-Notes-Fact-Sheet.pdf

- Jimenez, B. A., & Saunders, A. F. (2012). The additive effects of scripted lessons plus guided notes on science quiz scores of students with intellectual disability and autism [Abstract]. The Journal of Special Education, 47(4), 1-14. Retrieved July 6, 2016, from http://sed.sagepub.com.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/content/47/4/231.full.pdf+html

- Information, P. U., Technology, & Reid, P. (n.d.). Guided Notes. Retrieved July 6, 2016, from https://www.itap.purdue.edu/learning/innovate/hdiseries/notetaking/guided.html

- Inclusion Strategies for Secondary Classrooms: Keys for Struggling Learners (2010) https://www.itap.purdue.edu/learning/innovate/hdiseries/notetaking/guided.html

- Larwin, Karen H., Daniel Dawson, Matthew Erickson, and David A. Larwin. “Impact of Guided Notes on Achievement K-12 and Special Education Students.” International Journal of Special Education 27.3 (2012): 108-17. Web. 14 July 2016. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1001064.pdf