What was often mistaken for a small Sunday afternoon book club at the Victorian house on 31 Inman Street in Massachusetts, actually turned into a major cultural movement. Who would’ve thought that from this a boom in African-American poetry known as the Dark Room Collective would come about.

This boom did not focus on the negative aspects of African-American history, but more on the up-lifting side. The group didn’t whine, they didn’t so much want to argue, or to focus on the hard times in their heritage, but they wanted to show the world the imagination that can be gained from their history.

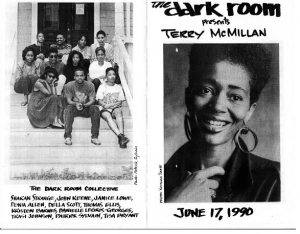

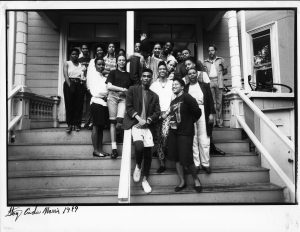

Picture this: every Sunday the house of Thomas Sayers Ellis and Sharan Strange was transformed into a studio, or a type of performance. Many say that no one even knew who lived there and who didn’t at times as the crowds grew more and more each week. As time went on, the series began to extend to musical performances, art shows and even workshops for writers of color in the community. The reading series was started with a simple purpose, for black writers to embrace their heritage and to be proud of it. The overarching mission of the Collective was to form a community of established and emerging African-American writers

Soon enough word got out, and the series blew up! From thrown together to an organized group, the Dark Room Collective was now composed of a melting pot of races, ethnicities and ages. Eventually, the group had to find a new home that would fit the entire family. The group relocated to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston when it outgrew the living room in Cambridge. In 1994, the group packed up and moved again to relocate to the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre at Boston University.

The Dark Room Collective stopped after a decade or so, however, some of its members in their 40s, had gone on to become famous literary figures winning major prizes. One example is Natasha Trethewey, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her book in 2006, “Native Guard,” and is the nation’s poet laureate. Other famous poets from dark room collective: Tracy K. Smith won the Pulitzer for “Life on Mars” in 2012, writers Kevin Young, Carl Phillips and Major Jackson have all been recognized as prolific and influential voices in American poetry.

In a way, the Dark Room Collective was a collaborative way for writers to say, “Let’s celebrate saying, ‘Hell yeah! This is our heritage, and this is how we can tell the world!’” In a New York Times article by Jeff Gordinier he quoted Mr. Adrian Matejka, who is part of a poetic organization that came out of the Dark Room Collective. Matejka described the Dark Room Collective as a “shift out of the ‘I’m a black man in America and it’s hard’ mode” into “the idea of ‘you are who you are, so that’s always going to be part of the poem,’ ” with “a lot more room for the sublime experience of language.”

More poems by Tracy K. Smith: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/55520

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/56376

BY KEVIN YOUNG

More poems by Kevin Young: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/58069

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/49763

Resources:

“A Brief Guide to the Dark Room Collective.” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, 9 May 2004, www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/brief-guide-dark-room-collective.

Gordinier, Jeff. “The Dark Room Collective: Where Black Poetry Took Wing.” New York Times, 27 May 2014, www.nytimes.com/2014/05/27/arts/the-dark-room-collective-where-black-poetry-took-wing.html?_r=0.

“The Dark Room Collective, Then and Now.” Poets and Writers, www.pw.org/content/the_dark_room_collective_then_and_now.