By Mattie Green

When reading Dr Faustus’ conversation with Mephastophilis about astrology, it immediately reminded me of one of the biggest scientific controversies of all time: Galileo’s proof of the Heliocentric model. It made me wonder if Marlowe wrote some of the play as a commentary of Galileo’s discoveries. Everything seemed to add up to that being the case (Faust getting questions about astrology answered by a demon, references to the Catholic approved Geocentric model, etc.) except for one very important detail: Marlowe’s Dr Faustus was first performed in 1592, and it wasn’t until after 1600 that Galileo’s research became known to the Roman Catholic Church. So why does the story of Dr. Faustus sound so similar to Galil eo’s trial?

eo’s trial?

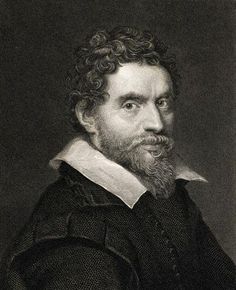

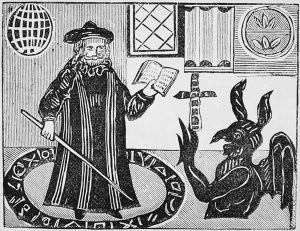

It starts with a man, one Johann Georg Faust (aka John Faustus, Georgius Faustus Helmstet, Georgius Sabellicus, Georgius Helmstetter… well, you get the point… Faust was a man of many names). This man was the, shall we say, inspiration for the book The History of the Damnable Life, and Deserved Death of Dr. John Faustus, which was then adapted into The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus by Marlowe. The real life Faust is believed to have gone to Heidelberg University from 1483 to 1487, and traveled Germany for the next 30 years as a physician, philosopher, professor, alchemist, magician, and astrologer (though he also became well known as a trickster and fraud, and was even denounced by the Church as a “blasphemer in league with the devil”). His death was dated to around 1540, and it was rumored that he died during an alchemical experiment gone wrong, which led to the myth that the devil had come to collect him. These rumors spread, and by around 1570 Faust was somewhat of a legend in Germany.

And so The Faustbook was born, er, written in 1587, and translated into The History the Damnable Life, and Deserved Death of Dr. John Faustus about a year later. Marlowe adapted it into play form soon after, and that, too, was extremely popular.

However, the Dr. Faustus’ character was adapted as well, and ended up being much different from the man he was based on. In the play, he seems like an agreeable fellow, except he badly misinterprets a passage from the Bible and comes to believe that he will go to Hell no matter what. I found this change in the character extremely interesting. Why would Marlowe go to the trouble of making Faust more likable when the audience would probably already know Faust messed up… big time?

The main reason I could think of was to create a hope of redemption for the character… similar to the scholars telling Faustus to repent to God and get out of going to Hell. Faust could have been redeemed, but he held onto his misinterpretation of the Bible, and that led him to his fate. It acted as a warning that misinterpreting the text could be a deadly mistake.

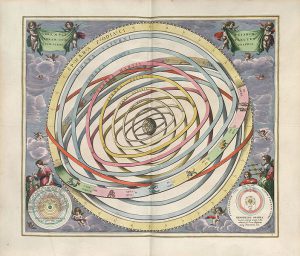

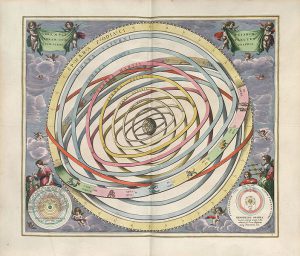

Prior to Galileo’s discoveries, it was widely believed that the entire universe rotated around Earth (the Geocentric model, above). The Church played a large role in the acceptance of this model, as the Bible itself was believed to contain evidence of the earth being the center of everything. Throughout the Bible there are references to “Earth standing still”, which, at the time, the Church took quite literally, instead of how we say “the sun sets or rises” instead of the Earth turning. Even the Dr. Faustus in the play believes in the Geocentric model,

“Come Mephastophilis, let us dispute again,

And reason of divine astrology.

Speak, are there many spheres above the moon?

Are celestial bodies but one globe,

As is the substance of this centric earth?…

But tell me, have they all one motion, both

situ et tempore [in position and time]?…

But tell me,

hath every sphere a dominion or intelligentia?”

All of Dr. Faustus’ questions to Mephastophilis about astrology relate to geocentric model ideas: that all planets and stars are one big globe, with earth at the center, revolving around the earth together, or even being moved or guided by angels. The most interesting thing about their conversation is the fact that Mephastophilis seems to be avoiding the questions and giving half-hearted answers, which Dr. Faustus catches on to: “These slender questions Wagner can decide: Hath Mephastophilis no greater skill?”. This scene seems to be a demonstration of sorts that the already accepted Geocentric model is more accurate than anything a demon could tell you, like only the Church has the true answers…even to astrology.

Which brings us back to Galileo.

When Galileo started to discuss his astrological findings and published his book, Sidereous Nuncius, the Church basically saw it as an attack on the Bible, going against the literal meanings of the words written. Galileo wasn’t the first to suggest a Heliocentric model, but, with the help of his trusty refracting telescope, he discovered Venus has phases and Jupiter has moons of its own, which were highly indicative of the Heliocentric model being correct. In 1616, the Inquisition declared Heliocentrism to be heretical, banning all books that supported it, and ordering Galileo to back off the topic entirely. However, in 1632, Galileo published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, which was a big hit. Since it largely supported Heliocentrism, the Inquisition tried Galileo and sentenced him to “indefinite imprisonment”, so he basically lived under house arrest for the rest of his life.

So, though I thought originally that The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus might have been an indirect commentary on the Galileo controversy, demonstrating the “evil” of astrology and science, it was written as a parody of the real Faust’s life. Overall, the greatest similarity between The History of Dr. Faustus and the Galileo Trial was that both Dr. Faustus and the Church misinterpreted the Bible which, in Dr. Faustus’ case, led to his death, and, in the Church’s case, led to the banning of the Heliocentric model and condemnation of Galileo. It wasn’t until 1822, when it was pretty well known that earth wasn’t the center of the universe, that the Church lifted the ban on Galileo’s books, and not until 1992 that the Vatican made a public apology, clearing Galileo’s name.

Citations

“By Placing the Sun at the Center of the Solar System”. History of Astronomy. Web. 05 Nov. 2016. <http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast121/lectures/lec02.html>

“Catholic Church Apologizes to Galileo”. Baskent.edu. N.p., 14 Sep. 2008. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <http://www.baskent.edu.tr/~tkaracay/etudio/agora/news/Galileo.html>

“The Galileo Controversy”. Catholic Answers. N.p., 10 Aug. 2004. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <http://www.catholic.com/tracts/the-galileo-controversy>

“The Magician, the Heretic, and the Playwright: Texts and Contexts”. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. N.p., N.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <https://www.wwnorton.com/college/ english/nael/16century/topic_1/faustbk.htm>

“What Galileo Actually Proved and Disproved”. The New York Times. N.p., 17 Nov. 1992. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.<http://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/17/opinion/l-what-galileo-actually- proved-and-disproved-595492.html>

Zweerink, Jeff, Dr. “Understanding the Galileo Trial.” RTB 30. N.p., 13 Oct. 2010. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <http://www.reasons.org/articles/understanding-the-galileo-trial>

Image Citations

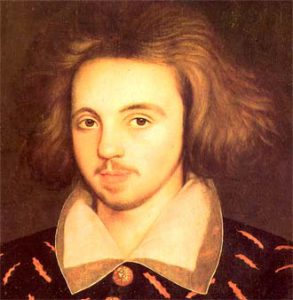

Galileo Galilei. Digital image. The Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. N.p., 13 Feb. 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <https://santacroceinflorence.wordpress.com>.

Johann Georg Faust. Digital image. Alchetron. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <http://alchetron.com/Johann-Georg-Faust-1057835-W>.

Old Geocentric Model. Digital Image. MHSP. 27 Jul. 2011. Web. 5 Nov. 2016. <http://milehighsanityproject.com>

ack and fell in love with a lovely girl by the name of Anne More. Of course this is where his luck begins to change for the worse. He elopes with her, but is later arrested and thrown in jail along with his love. A minister marries them officially there but the father of the bride refuses to accept it and therefore refuses to hand over her dowry. While married he had many children and it is not with their life, but their death that Donne’s obsession was revealed. With his wife he had twelve children but just over half of them survived, driving Donne into an ever deepening despair, pondering suicide as the escape from his misery, “I flatter myself with this hope that I am dying too, for I cannot waste faster than by such griefs” -John Donne. It was in the throes of this despair that he wrote Biathanatos, his defense of suicide, almost an attempt to absolve himself of what he might do despite the strict Catholic teachings against it. Donne tried to support his view by claiming that Christ committed suicide by voluntarily going to the cross, and therefore in the effort of all Christians to be Christ-like, suicide is acceptable. Of course it must be worth noting that by this point his Catholic upbringing failed him completely and he made the switch to the Church of England.

ack and fell in love with a lovely girl by the name of Anne More. Of course this is where his luck begins to change for the worse. He elopes with her, but is later arrested and thrown in jail along with his love. A minister marries them officially there but the father of the bride refuses to accept it and therefore refuses to hand over her dowry. While married he had many children and it is not with their life, but their death that Donne’s obsession was revealed. With his wife he had twelve children but just over half of them survived, driving Donne into an ever deepening despair, pondering suicide as the escape from his misery, “I flatter myself with this hope that I am dying too, for I cannot waste faster than by such griefs” -John Donne. It was in the throes of this despair that he wrote Biathanatos, his defense of suicide, almost an attempt to absolve himself of what he might do despite the strict Catholic teachings against it. Donne tried to support his view by claiming that Christ committed suicide by voluntarily going to the cross, and therefore in the effort of all Christians to be Christ-like, suicide is acceptable. Of course it must be worth noting that by this point his Catholic upbringing failed him completely and he made the switch to the Church of England.

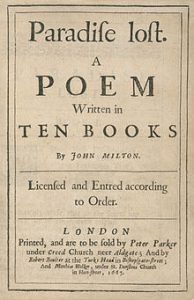

in loss of eyesight. Milton was completely blind by the year 1652. However, the precise cause of his blindness is unknown. We can only speculate. However, an alternative to how Milton lost his sight is that he worked so tirelessly for the Puritan and Oliver Cromwell cause he wrote himself blind. Milton wrote a series of pamphlets advocating for radical politics, some of his better-known topics being divorce and freedom of speech. GOOD THING these ideas are no longer radical. As Milton spent so much of his time defending his beliefs of divorce, freedom of speech, and populism he steadily lost his eyesight until he was totally blind. But truthfully, it could have just been glaucoma.

in loss of eyesight. Milton was completely blind by the year 1652. However, the precise cause of his blindness is unknown. We can only speculate. However, an alternative to how Milton lost his sight is that he worked so tirelessly for the Puritan and Oliver Cromwell cause he wrote himself blind. Milton wrote a series of pamphlets advocating for radical politics, some of his better-known topics being divorce and freedom of speech. GOOD THING these ideas are no longer radical. As Milton spent so much of his time defending his beliefs of divorce, freedom of speech, and populism he steadily lost his eyesight until he was totally blind. But truthfully, it could have just been glaucoma. . At this time Brail hadn’t even been invented but Milton still wrote. (How impressive.) Of course he had help from aids, most notably Andrew Marvell. Many of his greatest pieces were published after his blindness, including Paradise Lost. He is also noted for speaking out about his blindness and even writing poetry about his loss of sight.

. At this time Brail hadn’t even been invented but Milton still wrote. (How impressive.) Of course he had help from aids, most notably Andrew Marvell. Many of his greatest pieces were published after his blindness, including Paradise Lost. He is also noted for speaking out about his blindness and even writing poetry about his loss of sight. So, keep John Milton in mind next time you’ve sat in front of the computer for hours on end straining your eyes. It might affect your sight more than you know.

So, keep John Milton in mind next time you’ve sat in front of the computer for hours on end straining your eyes. It might affect your sight more than you know.