DNA has been used as a form of evidence for years and is now accepted as one of the more reliable ways of connecting a person with a crime. However, recently police have begun using familial DNA to identify suspects without having an exact match for their DNA. This brings with it several legal and ethical issues, which we’ll talk about.

What has past testing looked like?

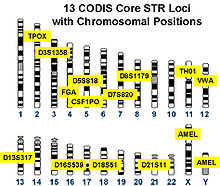

- The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) is software to store DNA from convicted felons and use it to identify whether any of that stored DNA matches an unknown sample.

- They match alleles at 13 specified locations in the samples and depending on the strength of the tests, it must match a certain number of the locations.

- A typical test used to identify a suspect is at the strongest level, where all 13 must match.1

What is Familial DNA Search?

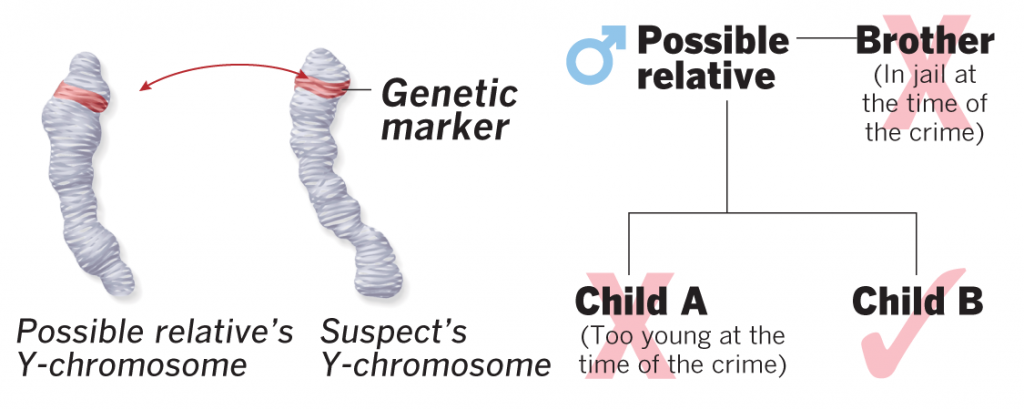

- A familiar DNA search uses a different software to list the likely candidates for close family relations and ranks them, then using lineage testing to confirm close candidates.

- This is different than partial matching, which simply identifies candidates who only meet a certain level of matches STRs without using lineage testing.

- Y-STR testing, one form of lineage testing, looks specifically alleles on the Y-chromosome which allows you to look at fraternal connection. This highlights one of the current drawbacks of familial searching, which is that it currently can only identify male relations.1

When is familial DNA testing used?

- Familial DNA is used only as a last resort when no other DNA testing has worked thus far. It also has typically only been used for major cases.2

- Familial DNA is also an expensive option for labs—Y-STR testing is currently not regularly used in normal testing, so the additional tests must be purchased for familial DNA. Additionally, much of the current software is slow, making the process use up valuable time and resources, and must be purchased or developed in house by a jurisdiction.3

What are some of the concerns about Familial DNA?

- The first major concern about familial DNA searches is that it violates your 4th amendment privacy rights. While many accept that upon being convicted for a crime, you give up some of your privacy rights which allow for collection of criminal DNA, it is not widely accepted that those rights apply to your family. By using criminal DNA to conduct familial DNA searches, you are infringing on the rights of family members.

- The next major concern is that familial DNA is discriminatory, since there is a larger pool of samples for African Americans since they are more likely to be incarcerated and have DNA samples collected. This would make it easier to find matches for African American suspects versus other races.2

Familial DNA searches could make DNA searches for criminals vastly more effective, with one study seeing a 40% increase in the likelihood of finding a relative for an unknown DNA sample through this method versus finding a direct match through traditional methods.4 However, I believe that we have not had the technology advances or worked through the legal implications of familial DNA searches enough to widely implement this process.

Our current methods don’t offer any equivalent for Y-STR testing which would help identify female relations, so we currently must rely on partial matches only. Additionally, fourth and fourteenth amendment rights are at stake, and we need to have a national discussion on how to protect those rights before implementing familial DNA searches widely. Still, in the famous cases which have already used this method, including the Grim Sleeper case, it is already clear that is certainly has the potential to find new, so far unidentified subjects to some of the most puzzling cold cases still open today.

1. National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Understanding Familial DNA Searching: Policies, Procedures, and Potential Impact, Summary Overview. 251043. August 2017. By Sara Debus-Sherrill and Michael B. Field.

2. National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Study of Familial DNA Searching Policies and Practice: Case Study Brief Series. 251081. August 2017. By Michael B. Field, Saniya Seera, Christina Ngyuen, and Sara Debus-Sherrill.

3. National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Study of Familial DNA Searching Policies and Practices: Cost Simulation Tool User Guide. 251045. August 2017. By Avi Bhati and Sara Debus-Sherrill.

4. Frederick R. Bieber, Charles H. Brenner, & David Lazer. (2006). Finding Criminals through DNA of Their Relatives. Science, 312(5778), 1315.