Jack Caiaccio

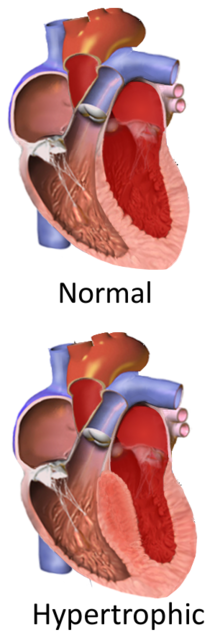

Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy is a rare heart condition where the heart muscle thickens, blocking blood flow to the body. The muscle thickening typically occurs in an area of the heart known as the interventricular spectrum, which separates the two lower chambers of the heart. In some patients this muscle thickening can lead to abnormally sounding heart beats, which can obviously be detected. In other cases, however, there may be no visible or audible symptoms, just slowed blood flow, which can be very serious. Regardless, the thickening of the muscles in the heart obstructs the flow of blood into and out of the heart, which can be fatal. The prognosis for individuals affected with FHC is relatively benign- those affected may live for years without any symptoms or issues. A study by Thoraxcentre in The Netherlands has shown that, “HCM has a relatively benign prognosis (1% cardiac annual mortality) that is 2-4 times less than previously thought.” According to the US National Library of Medicine, Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects an estimated 1 in 500 people worldwide. It is the most common genetic heart disease in the United States.” It is a gene that is autosomal dominant, so both parents must be at least carriers for the offspring to have a chance of having Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Autosomal means that the FHC gene is located on a non-sex chromosome, so both male and female offspring have an equal likelihood of receiving a copy. Dominant means exactly what is seems- it only takes one copy of the gene mutation to cause the disease. Therefore, when an offspring receives genes from its parents, it only takes one mutation in the MYH7 gene, or any other gene linked to FHC, to cause Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. There are close to ten genes with variations that could leave the patient affected by FHC. The most prevalent mutation is in the MYH7 gene, which is associated with about 35% of FHC cases.

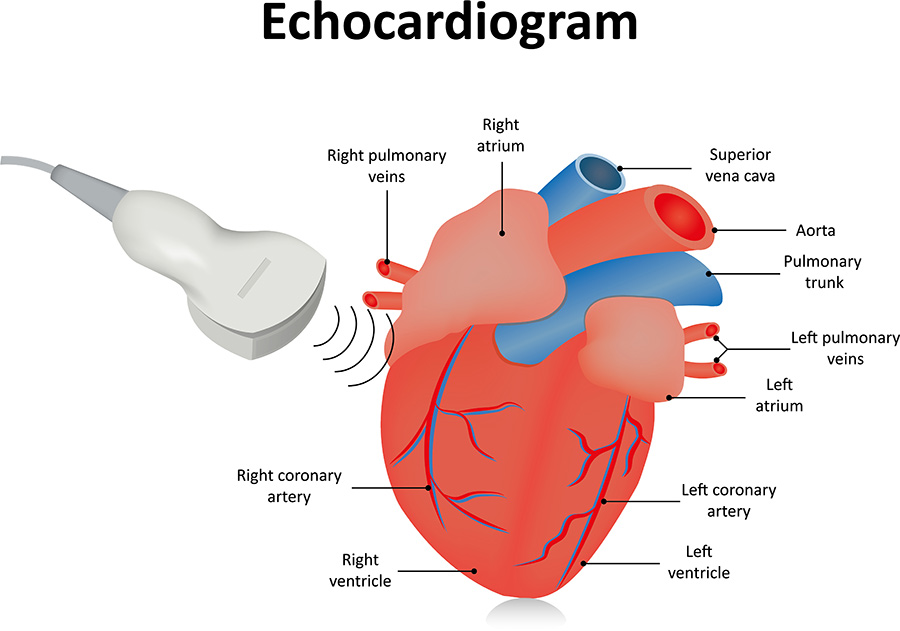

In order to identify Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, it is imperative to get tested. Testing can be especially important in athletes and highly active people, because they are the ones that are physically exerting themselves the most, and their heart rates are, on average, higher. When an athlete is playing a sport, such as basketball, their heart rate is high, and their heart is having to work harder in order to get oxygen-rich blood to the body. If muscle is thickened, it is more difficult for the heart to distribute blood to the body. At higher heart rates, the heart can become overworked and blood may cease flowing and clot, which can be fatal. The most effective way to test for FHC is through an Echocardiogram, which is an imaging test where a doctor can see if the heart muscle is abnormally thick. Genetic Testing is not the most effective way to test, as results may not provide any definitive answer. One reason for this, according to the Mayo Clinic, is that, “Only about 50 percent of families with HCM have a currently detectable mutation, and some insurance companies may not cover genetic testing.” I would recommend some form of monitor testing, something that allows doctors to see if the heart muscles are enlarged or not. It can cost up to two thousand dollars for an echocardiogram, and no options that test the heart are cheap. Without insurance, you may still need to pay the entire cost by yourself. With insurance that does in fact cover an Echocardiogram, there will still be a co-pay of up to one thousand dollars. Even genetic testing would be expensive to test for all the gene mutations associated with FHC.

Before getting tested for Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, it is important to know as much as possible about possible issues or limitations with the test. For example, there are about ten genes with variations, and some only account for a small increase in risk. Even with that mutation, it is still very possible that the patient will not have FHC. Also, there could be an undetected variation that the patient has that is not known to cause FHC, but it could because it just has not been associated to it yet.

There are many other possible repercussions to being tested for potential FHC. One is the possibility of your genetic information being sold to outside companies. Your genetic privacy is very important, and it could be a big problem if your information is sold. The company 23andMe is an online platform where you mail in a sample and get your results within a couple of weeks. According to the website, “Everyone deserves a secure, private place to explore and understand their genetics. At 23andMe, we put you in control of deciding what information you want to learn and what information you want to share.” There are also some potential downsides of being genetically tested for Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, mainly because only about half of the people who have FHC in their genetic makeup have a detectable gene that will show they have it. In addition, it is very difficult to live knowing you have Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, as you must exercise extreme caution whenever doing any physical activity. Treatment can help, and knowing about the disease could be lifesaving, especially for college athletes. College athletes, in particular, should know if they have FHC, because it could be lifesaving. It is important for all athletes to be tested, but I believe it should be required for collegiate athletes in the United States.

When being tested for Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, it is important to be educated and ask the right questions to the experts. It depends on the gene in question, but since FHC is autosomal dominant, if a parent has tested positive, then there is a good chance a child will also test positive, about fifty percent. According to the National Library of Medicine, “This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.” It also states that, “In most cases, an affected person has one parent with the condition.” If they test positive, they should consult with the doctor and ask about possible treatments to help with the condition and about what they should do regarding physical activity. If they test negative, they should still be careful about physical activity or maybe even get a second test if possible, because of how much of a toss-up genetic testing is for FHC. I would tell my doctor anything I know, because they probably know more than I do and could help me out in my lifestyle changes. If they test positive, I would recommend screenings like the echocardiogram, because it can be far more definitive than the genetic testing can be, and the doctor can tell you the level of severity at the given time. A positive test should result in significant changes to the affected person’s life. They should be very careful when doing any physical activity, and they should limit their exertion.

In conclusion, Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy is a very serious heart condition that is genetic. People who have it in their genetic history should definitely get tested. I would recommend first getting an echocardiogram, to test the heart valves and muscles associated with FHC. If they are in fact swollen or enlarged, then I would recommend the genetic testing for FHC. Even though the results are inconclusive, you may be able to conclude more after echocardiogram results have come back. For example, if you know that heart muscles have thickened, you could pair that information with your genetic testing in order to develop the most conclusive results possible. It is very important to detect it, as it could be lifesaving to know that you have it, because treatments and lifestyle changes can have big effects. Before being tested for FHC, it is imperative to know as much as you can about the tests and ask the right questions.

Sources

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – Genetics Home Reference – NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/familial-hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy#inheritance.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. (2018, April 14). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350204.

23andMe. (n.d.). Privacy and Data Protection. Retrieved from https://www.23andme.com/privacy/?vip=true.

Prognosis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Thoraxcentre, University Hospital. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10163618