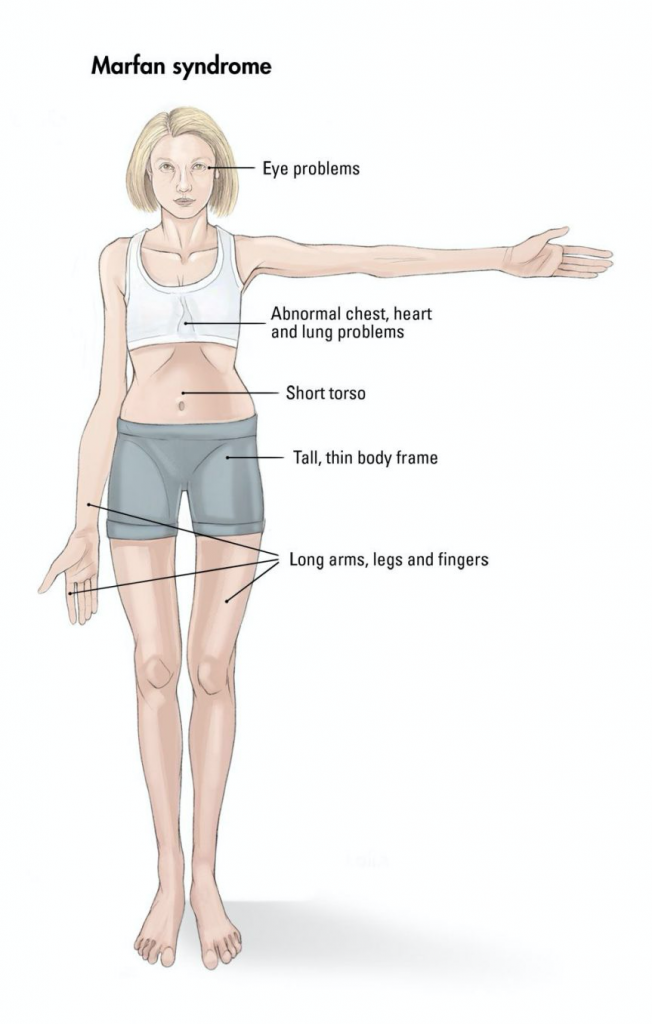

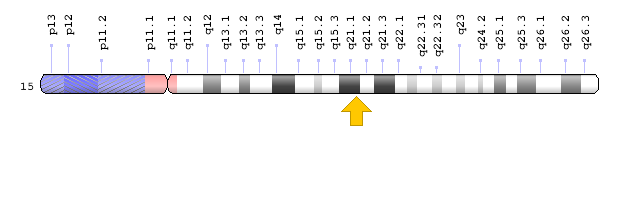

The trait I am testing for is Marfan Sydrome, an inherited genetic disease caused by a mutation in the FBN1 gene. While not very common, only occurring in around one in five thousand people (NIH), Marfan’s main symptoms are elongated limbs, worsened vision and heart issues. Only one gene is known to be the cause, and it can result from a change in any of the many alleles within the gene.

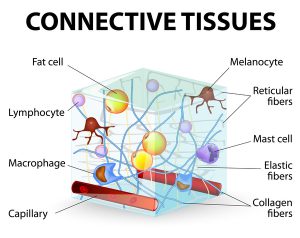

Marfan affects the production of fibrillin, a compound key to the extracelluar matrix and skeletal and muscular development1. The condition causes the afflicted to be taller than average, along with having thin arms and legs and possible heart issues. The above average height of those with Marfan can be very beneficial for athletes, especially basketball and volleyball players. Famous atheletes with Marfan include Olympic medalist Flo Hyman and basketball player Isaiah Austin. As the mutation affects the above developments, it makes sense that those carrying it have thinner, weaker muscles due to a less strong extracelluar matrix which provides support around cells through a compound called fibrillin. Marfan leads to decreased fibrillin production, and thus less strength and elacticity in tendons and muscles. This leads to those with Marfan tending to have longer, slimmer limbs and aorta issues in the heart.

Testing for Marfan would more than likely be done to test for the likelihood of the disease in offspring. The condition is not always obvious, depending on the severity of symptoms. A SNP-ChiP is best recommended, as this test can encompass the entire gene and detect any and all SNPs which have mutated, leading to the affliction2. There is no specific allele or SNP known as the cause, many different ones from FBN1 have been seen to cause Marfan3. This test can run anywhere from $200-$2000, depending on insurance and the laboratory running the test. There is a very strong connection between these mutations and the disease, as over a thousand alleles have been tied to it4 and if you have the mutation you will demonstrably have the disease. Getting a test done is most effective to determine risk in newborns to see if they will later develop symptoms. The risk of inheritance is fifty percent if one parent has the condition as it is autosomal dominant and those who carry the mutation are at a one hundred percent risk of developing symptoms.

Testing is not necessarily needed for this condition, but may be beneficial. Those who have any of the mutations will in many cases show symptoms and thus not need testing. Parents, however, can use testing to segregate eggs which do not carry a mutation and selectively breed children through invitro fertilization. The ethics around this are murky and can cause controversy. Adults with the condition commonly know they carry it and do not need to give up genetic information to a company just to discover they have a mutated allele they already knew about. From a scientific point of view, testing is not commonly needed. Those with symptoms should strongly consider getting tested. The main possible benefit would be that a positive would indicate possible heart issues, and further testing could be done. Getting a test done could also be beneficial for those without symptoms, as they may not visibly show it but could have Marfan and potentially develop complications. There are few ethical concerns around this kind of testing, with the only main exception being around in-vitro fertilization and selective breeding.

Family history plays a large part into having Marfan. If one parent has it, the child will have a fifty percent chance of having it as it is an autosomal dominant condition. Marfan is only inherited directly from an afflicted parent. One has a roughly one in twenty thousand chance of randomly developing it. There are no needed environmental adjustments needed if the test is positive however, as the disease is not affected by the environment. A positive or negative result from the test is only significant for a child who has not yet developed symptoms or for an adult with onlt one symptom. As Marfan is untreatable, in this case the parents could try to mitigate symptoms, but they cannot be fully treated. Adults who show as positive could also get screened for heart issues which are commonly tied to Marfan.

References

1. NIH. (2019, November 12). Marfan Syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/marfan-syndrome#.

2. Singh et al. (2015). Single-copy gene based 50 K SNP chip for genetic studies and molecular breeding in rice. Scientific Reports, 5(1). doi: 10.1038/srep11600

3. Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Test ID: FBN1B FBN1 Full Gene Sequence, Varies. Retrieved from https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/Clinical and Interpretive/64514.

4. SNPedia. (2018, December 8). Marfan syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Marfan_syndrome.