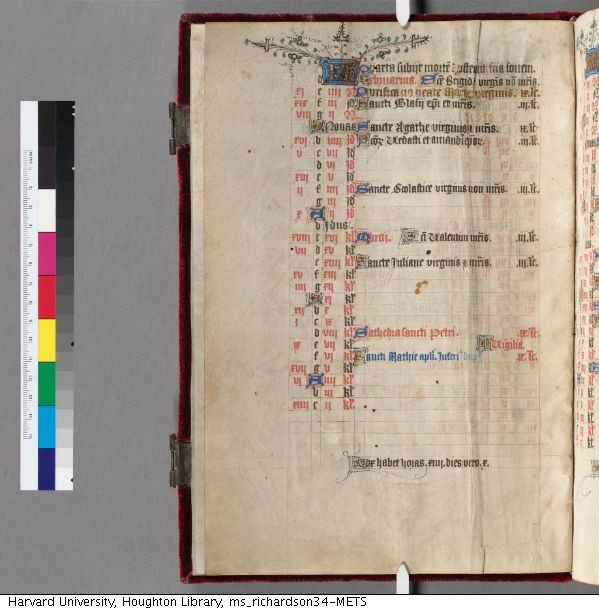

Religion is the sort of thing that resonates with people on a deeply personal level. As a whole, a book of hours is like a physical representation of someone’s personal take on their religion through their choices of contents. Many people focus on the individual aspect of the sections of psalms and prayers, but one of the most revealing things in a book of hours is the calendar portion. I recently spent a full day recording as much of the calendar in MS Richardson 34 at Harvard’s Houghton Library as I possibly could, and it was both fascinating and exhausting. I would probably not recommend doing this if it isn’t completely necessary.

Now, since the production of MS Richardson 34, the official calendar of saints has changed greatly. This means that many saints have been added since and many have been decanonized and removed from the calendar, which makes matching an entry in the manuscript to a saint a bit tricky. The very first name listed is Stephan on January 2nd. I had not been able to identify any Saint Stephan whose feast day is January 2nd. There are three possibilities for why this is:

- I have misread the name entirely and it isn’t Stephan.

- This saint has been decanonized and has fallen into obscurity.

- This saint is still canon, but his feast day has been changed for some reason.

Saints are decanonized by being removed from the official calendar, generally for having insufficient proof that they existed or did the things people claimed they did. The official position of the Vatican is that while these removed saints are no longer listed, it is up to the local levels of the church to decide whether or not to keep celebrating them(Paul). The most well-known decanonized saint would probably be Saint Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, who was considered a saint for carrying a child who turned out to be Jesus across a river. He is, by the way, not listed in this calendar.

As it turns out, the real solution was none of those things. This day marked in the calendar was the octave of St. Stephan the Protomartyr. An octave was a shorter celebration eight days after a saint’s real feast day. This was an honor reserved for the especially important saints. Octaves are particularly difficult to look up because most modern calendars only cover the actual feast days.

This particular manuscript supposedly belonged to a church in England. (Normally a book such as this would belong to an individual, but the Harvard bibliography claims it belonged to a church.) The evidence pointing to this is the mention of several saints who were only particularly popular in England- Wulfstan, Dunstan, Swithun, and Erkenwalde, for example. Dunstan in particular was the most popular saint in England for two hundred years(Dunstan). Swithun, who is listed twice, once on the feast day recognized in Norway, July 2nd, and once on the feast day recognized in England, July 15th, is a saint of weather. It is said that if it rains on Saint Swithun’s Day (the English one), it will continue to rain for forty days.

Being an English book of hours, it primarily follows the Use of Sarum, the calendar promoted by the Bishopric of Salisbury. There is a full version of what is considered the standard Use of Sarum here, though there are some small variations between books. For example, this book did not originally have Thomas of Canterbury on December 29th, but it was added by a later hand, which can be attributed to the book’s creation taking place before his addition to the calendar. It substitutes St. Serena for St. Germanus on May 28th. Other saints are added alongside the ones listed in the standard use.

These sorts of regional saints really bring out the regional aspects of religion, which can seem odd in today’s globalized culture and highly structured and centralized take on this sort of religion, but it makes more sense in the context of the time. When it can take weeks to reach a destination, things can become much more localized and individualized.

Sources:

Paul, VI. “Mysterii Paschalis.” Mysterii Paschalis (February 14, 1969) | Paul VI. Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 14 Feb. 1969. Web. 06 Oct. 2016.

“Who Was St. Dunstan?” St. Dunstan’s Episcopal Church. Web. 06 Oct. 2016.

The Sarum Missal In English. Issue 11, Part 1. London: A. R. Mowbray, 1913. Internet Archive. Web. 6 Oct. 2016. <https://archive.org/details/TheSarumMissalInEnglishIssue11Part1>.

Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis (Sarum Use). N.p.: n.p., n.d. Harvard University Library. Web. <http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL.HOUGH:1077863>.