Now I know what you’re thinking. And I can explain, just trust me.

Despite the obvious differences in form, production, and time, comic books, in many ways, carry over the special appeal of medieval manuscripts—namely, the intimacy of their handwriting. Like with manuscripts, which often retold stories, poems, prayers, and history through many different hands, comics too often retell and reshape culture, keeping the intimacy of their hand even as the work itself is xeroxed and mechanically reproduced.

And like with manuscripts, we as modern readers come to old comics always knowing how detached from their moment we are—not necessarily their historical context, though obviously that plays a role too, but the specific creative time in an individual creator/scribe’s life. Whether you’re reading a digital scan of The Canterbury Tales or a hardcover copy of Maus, there persists the ever-present awareness that someone somewhere had to sit down at their desk and create this with their hands.

That’s what I want to examine over the course of the next three posts: the intimacy of comics as a form, and how these feminist comics from the early 1970s used said form to perform their politics. Similar to how a monastery might perform their loyalty to the king by commissioning a lavishly decorated manuscript to gift to him, the comics analyzed here use their form, production, and distribution to perform an often-playful, sometimes-aggressive, and always-transgressive second-wave feminism.

I know we medievalists love to gush over the gold lettering in our manuscripts, but for these particular comics, in order to understand how and why they came to be, we’ll instead have to start with silver.

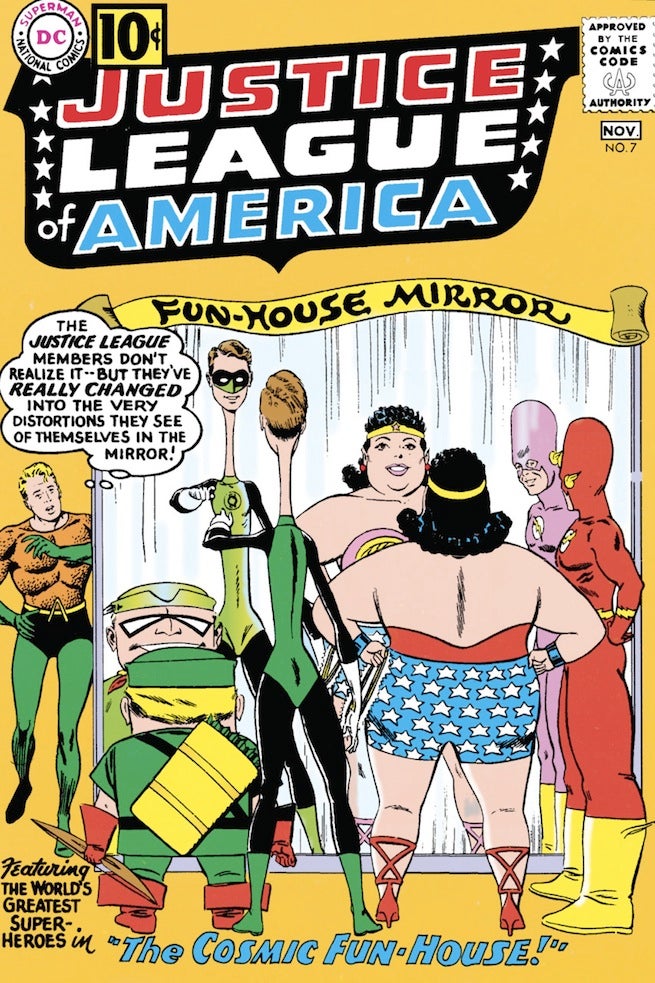

“The Silver Age” of comics, roughly agreed to have lasted between 1956 and 1970, is remembered as a period of great commercial success for superhero comics, as well as the origin or rebirth of many of the most beloved superheroes of all time (Reynolds 9).

I’ve also been told by many friends that it was a supremely silly era.

The emphasis, however, is on superhero comics—and the reason for that has everything to do with that little “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” stamp up in the top righthand corner.

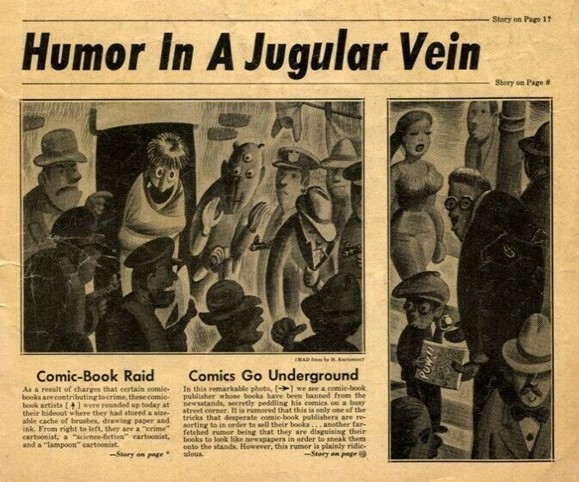

While comic book-inspired media has become a major cultural force in recent years and has come to encompass a wide range of age demographics—from family-friendly movies like most MCU and DCEU fare, to hyperviolent adult-oriented shows like Amazon’s Invincible and The Boys—I think it’s still fair to say that comics have a reputation as more “juvenile” media, a reputation which even some of the darker takes I just listed play off of. Regardless of its accuracy, this “juvenile” reputation came to a head in 1954, when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published his bestselling philippic Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comics Books on Today’s Youth, and later testified about the detrimental effects of comic books before the US Senate.

This would result in the formation of the Comics Magazine Association of America and the “Comics Code,” an industry attempt at self-regulation that severely censored the types of content allowed in mainstream comic books (Chute 100). How bad was it? One of the rules was, and I’m not kidding, “No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title” (“The Comics Code of 1954”). A few other highlights include:

- Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

- In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

- The letters of the word “crime” on a comics-magazine cover shall never be appreciably greater in dimension than the other words contained in the title. The word “crime” shall never appear alone on a cover.

- Although slang and colloquialisms are acceptable, excessive use should be discouraged and, wherever possible, good grammar shall be employed.

- Divorce shall not be treated humorously nor represented as desirable. (“The Comics Code of 1954”)

As you might imagine, this Code took most of whatever creative momentum the medium had been building and slammed it right into a brick wall—and directly led to the start of the Silver Age, as publishers turned towards child-friendly superhero titles to keep their presses running. Everyone else went underground—publishing their comics with small presses and creators’ collectives and selling them in headshops, record shops, and independent bookstores (though legend still holds that Robert Crumb sold the first issue of his revolutionary comix Zap from a baby carriage at the corner of Haight and Ashbury) (Cunnelly 45).

Unlike the Silver Age, however, the underground comix movement would not truly begin until 1968 with the publication of Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix, the first title from indie San Francisco imprint Apex Novelties (Chute 103). The tagline? “Fair Warning: For Adult Intellectuals Only!” As comics scholar Hillary Chute writes,

Underground comics, often deeply concerned with form, anticommercial, and oppositional to mainstream mores, were not trying to adhere to an established notion of what avant-gardism meant; rather, they sought to invent the notion of an avant-garde afresh— sacrificing none of the fascination with form in also investing in the populist idea of accessibility and inexpensive publication and circulation. (103-104)

In other words: comix sought not only to play with the medium of comics itself, but to play jump-rope with the line between low-brow “trash” and high-brow art. Thus, for the purposes of these posts, I’ll be using “comics” to describe individual stories or the issues of Wimmen’s Comix as objects—things you hold in your hand and read without necessarily thinking of where they came from—, whereas “comix” will be used to discuss the issues as products of their unique historical context.

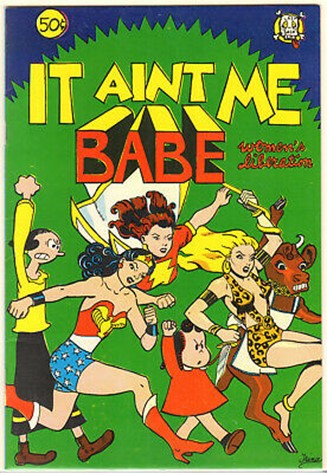

Around this same time, the Women’s Liberation movement, now better known as “second-wave” feminism, was also causing political uproar—especially in regards to women’s rights to free sexual expression and access to reproductive healthcare like abortion. The deeply political and transgressive nature of comix seemed a perfect place to translate this energy, yet many female comics authors found themselves othered by the chauvinist atmosphere the underground comix scene had quickly developed. Trina Robbins, one of the most noteworthy authors from this period, says that “the big problem, if you were one of the few cartoonists of the female persuasion, was that 98% of the cartoonists were male, and they all seemed to belong to a boy’s club that didn’t accept women” (Cunnally 49).

This is not to say that female comics creators were completely absent in the early years of the movement, but it was not until July 1970 with the publication of It Ain’t Me Babe, edited by Trina Robbins and published Last Gasp Eco-Funnies, that the first comic book produced entirely by women appeared. What Zap did for underground comix, Babe did for women in the comix space. As John Cunnelly counts, before the publication of It Ain’t Me Babe, only 43 out of 228 comix titles included at least one identifiably female artist—and even then, it was usually just the one. Women contributed 71 out of 1,177 comics to these titles, or about 6%. After the publication of Babe, however, 911 out of the 8,911 individual comics published between 1971 and 1982 were authored by women, raising that percentage to roughly 10% (Cunnelly 52). While this number is still small, it’s undeniable that It Ain’t Me Babe opened the gates for women entering the comics industry.

This, finally, leads us to Wimmen’s Comix, which ran from 1972 to 1992 and openly announced its intentions of helping women enter the industry. While the all-women editorial team rotated, each issue relied on submissions from across the country, placing “no-names” besides established creators like Trina Robbins, Sharon Rudahl, Lee Marrs, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Later contributors would include M.K., Alison Bechdel, Phoebe Gloeckner, and even Sophie Crumb, the then-seven-year-old daughter of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Robert Crumb (Miller 303).

Furthermore, the “revise-and-resubmit” submission system (seemingly employed by many comix anthologies if said anthology was not already full of the editors’ friends) provided encouragement and mentorship for these budding creators. The R&R system also created what scholar Leah Misemer calls “correspondence zones,” wherein readers can become creators and directly respond, sometimes even critically, towards the comics they’re fans of (191). Not only were readers encouraged to submit their feedback, dick pics, and comics, said comics were allowed to openly riff off of previous works in the series.

In the next post, I’ll be examining Wimmen’s Comix #3, “Fun and Games,” which was published in January 193 by Last Gasp Eco-Funnies, the first of three publishers Wimmen’s Comix would use. It truly has it all: calls for audience participation, experiments with form, passive-aggressive jabs at other feminist media producers, satire, autobiography, sex, abortion, board games, castration, and even spaceships!

It’ll be fun, just trust me!

***

Works Cited

Chute, Hillary. “Time, Space, and Picture Writing in Modern Comics.” Disaster Drawn : Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016, pp. 69–110.

Cunnally, John. “Before the Babe and After: Counting Women Cartoonists in the Underground Comix.” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 40, no. 1, 2020, pp. 44–54.

Reynolds, Richard. Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology. University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

Miller, Rachel. “Revolution Girl Style Later: Intergenerational Feminisms and the Second Life of Wimmen’s Comix in the 1980s.” The Other 1980s : Reframing Comics’ Crucial Decade., edited by Brian Cremins and Brannon Costello, Louisiana State University Press, 2021, pp. 303–17.

Misemer, Leah. “Hands Across The Ocean: A 1970s Network of French and American Women Cartoonists.” Comics Studies Here and Now, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama, Routledge, 2018, pp. 191–210.

“The Comics Code of 1954—Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America, Inc.” Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, originally published 26 Oct. 1954, http://cbldf.org/the-comics-code-of-1954/.