[Warning: This post contains discussions of sexual assault.]

Way back in my first post, I claimed that Wimmen’s Comix performed an “often-playful, sometimes-aggressive, and always-transgressive” form of feminism. And it’s that word “perform” that I want to linger on for a moment. These days, calling someone’s activism “performative” implies that it’s self-serving and has little to no impact on the actual topic or marginalized group in question—perhaps the most relevant example here being men who declare themselves to be great feminists and Certified Women Respecters in public spaces solely to try and get laid.

“Performative,” as it’s used here, means “fake.” But I don’t want to use it that way. Judith Butler, in her essay “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” writes that

Gender is in no way a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceede[sic]; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time—an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts. . . a constructed identity, [and] a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief. (519 – 520)

What all of that means, essentially, is that being a specific gender means performing specific acts over and over again, to the point that both audience and actor believe the performance to be true.

If gender roles are performative, then breaking them is, too. To bring this back to Wimmen’s Comix, take the space in Wentzell’s “Great American Dream Scream Game” wherein the player advances one space because she’s “burned her bra.” Bra-burning as a feminist ritual means nothing without the belief that bras help reinforce the idea that women’s breasts are innately more sexual and “obscene” than men’s. Burning your bra, then, announces your feminist ideals to the world while also reinforcing your own belief in them—after all, you’d look quite silly making a scene like that and then going back to meekly following men’s orders.

The Collective behind Wimmen’s Comix consciously used the production and distribution of their art to perform their feminism. As stated back in my first post, Trina Robbins and the other Collective members began the series to help fellow female artists break into a male-dominated industry, giving them a space to tell the stories of love, sex, heartbreak, abortion, and high fantasy that they weren’t allowed to discuss in “polite” society. But it doesn’t stop there. While other feminist publications such as Ms. Magazine rejected the comix as being too “crude” or “decadent” or “obscene,” the Collective themselves sometimes disagreed with how their feminist ideals should be implemented. Kominsky-Crumb, one of the founding members of the Wimmen’s Comix Collective, initially felt unsupported by the other editors because her comics lacked “political correctness” and didn’t cause “a significant raise in the level of feminist consciousness” (whatever that means) (Chute 23). In 1976, Kominsky-Crumb and fellow cartoonist Diane Noomin started their own comic book, Twisted Sisters, which rejected what they saw as the “almost superhero-inflected glamorization of women under the auspices of feminism” (Chute 24). How can you tell? Well, the first cover of Twisted Sisters shows Kominsky-Crumb sitting on the toilet, looking into a handheld mirror.

Furthermore, despite the diversity in topics and genres, the beginning issues of Wimmen’s Comix were limited in their representations of different womanhoods. Hillary Chute says that in 1973, “reacting specifically to the perceived heterosexism of Wimmen’s Comix—which featured no gay characters—Mary Wings self-published Come Out Comix on an offset press and so created the first lesbian comic book” (24). However, it would be more accurate to say that those first few issues lacked not gay characters, but gay perspectives. Issue 1 of Wimmen’s Comix featured a short comic by Trina Robbins entitled “Sandy Comes Out,” in which the narrator’s titular friend, Sandy, comes out as a lesbian and invites the narrator to a gay bar. Not only that, but this comic directly inspired another cartoonist, Robert Gregory, to publish her own from a sapphic perspective. As Gregory herself says, “I remember seeing the first couple of issues and Trina had her ‘Sandy Comes Out’ story. And I thought, ‘Well, she’s telling about her lesbian friend. That means I could tell a lesbian story’” (Misemer, “Counterpublic” 9).

This is what Leah Misemer means when she claims that the revise-and-resubmit system employed by Wimmen’s Comix constituted a “correspondence zone”—by publishing Gregory’s “A Modern Romance” in Wimmen’s Comix #4 despite her overt critiques of the heterosexual, “tourist” perspective employed by Robbins in “Sandy Comes Out,” Wimmen’s Comix created a space where different avenues of womanhood could be explored within the same series. (This is not to undercut any of Kominsky-Crumb’s complaints, but it’s also worth noting that this disagreement didn’t cause any irreparable rift between her and the rest of the Collective. After all, she and her then-7-year-old daughter would both appear in the 1991 issue “Little Girls,” creating a unique correspondence zone where mother and daughter both freely discuss their differing perspectives on parenting and growing up.)

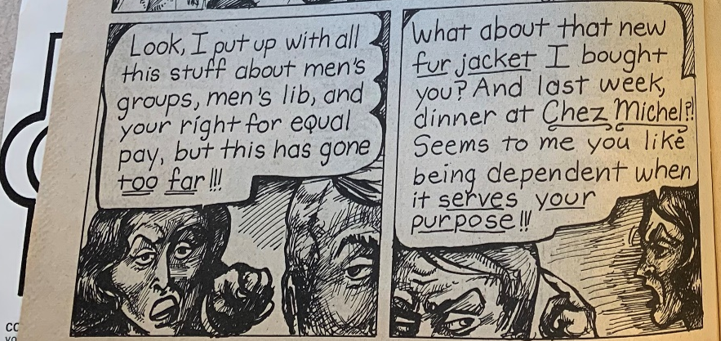

Misemer also calls Wimmen’s Comix a “counterpublic” within both American culture and the underground comix movement itself, due to the subversion of their “sexualized visual idiom”—which is to say that, by referencing sexualized representations of women in broader culture (and underground comix as a whole, which were often incredibly sexually explicit), Wimmen’s Comix maintained an awareness of the broader culture they were defining themselves as against (“Counterpublic” 7). For example, the “Fun and Games” issue begins with Dot Butcher’s short comic “A Sordid Affair,” wherein a businesswoman arrives uninvited to her male partner’s house and coerces him into sex using the exact same script many women are all-too-familiar with. The woman complains about having to “put up with” men’s demands for rights such as equal pay, while lines such “What? You have a headache?” sardonically echo the common trope of a woman feigning illness to get out of performing sexual acts with a partner who refuses to leave her alone (Butcher, panels 9, 21). Flipping this “script,” then, highlights the sexual violence embedded in many heterosexual relationships by defamiliarizing its language.

Other examples of this kind of recontextualization abound. As Misemer writes, these comix “adapted various marginalized media, from obituaries to popular songs and myths to letters, into comics form, positioning comics within a genealogy of American feminist media that stretched throughout time” (“Hands Across the Ocean” 191). Issue #3 contains the obvious “Rosie the Riveter” fanfiction discussed in my last post, but others would include Melinda Gebbie’s “Ten Cents A Dance,” published in Wimmen’s Comix #6 in 1976 and based on the popular 1930 song of the same name. “Ten Cents a Dance,” both the song and the comic, depicts the trials and tribulations of a professional dancer. The anguish behind lyrics like “Ten cents a dance, that’s what they pay me / Gosh, how they weigh me down” is literalized by the fear, boredom, and later tears Gebbie draws on the dancer’s face (Misemer, “Hands Across the Ocean” 200). Further, as Misemer points out, the coda image of a man performing oral sex on the woman appears below the comic, “outside the frame, so as to call attention to the fact that there is no place for her pleasure or desire in the lyrics of the popular song” (“Hands Across the Ocean” 246).

Thus, as Misemer writes, the unique verbal-visual languages of comics and their authors’ common willingness to poach from popular culture “help[s] flesh out smaller stories from the [feminist] archive, filling in gaps and encouraging people to remember the women of history” (“Hands Across the Ocean” 246).

I could go on like this for hours, but I think you get the idea. While often satirical, silly, irreverent, and even discomforting, the comix collected in Wimmen’s Comix showcase not only the special, hypermediated pleasures of comics as a medium, but demonstrate ways in which comix can be used to carve out spaces for women’s voices and allow multiple facets of womanhood, no matter how “deviant,” to receive recognition.

***

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal, vol. 40, no. 4, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988, pp. 519–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

Chute, Hillary L. “Introduction: Women, Comics, and the Risk of Representation.” Graphic Women : Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics., Columbia University Press, 2010, pp. 1–27.

Misemer, Leah. “Hands Across The Ocean: A 1970s Network of French and American Women Cartoonists.” Comics Studies Here and Now, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama, Routledge, 2018, pp. 191–210.

Misemer, Leah. “Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen’s Comix.” Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, vol. 3, no. 1, Ohio State University Press, 2019 Spring 2019, pp. 6–26. MLA International Bibliography.

Women’s comic book collection, ms4091, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, The University of Georgia Libraries.