This is a story. Actually, it’s several different stories. It could be the story of How I Spent My Summer Vacation. It’s in part a story of collaboration and academic generosity. But it’s definitely a story of how teaching these classes has made me better at the research-and-writing part of my job.

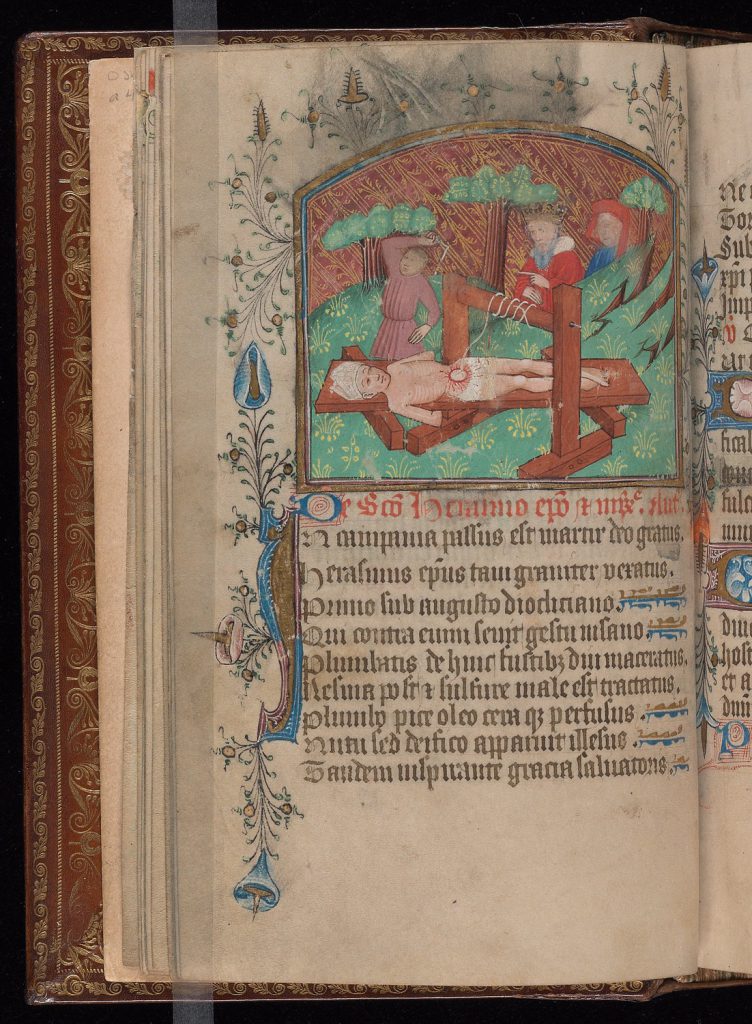

This early summer I’m finishing an article on the Middle English poetic Life of St. Erasmus. Erasmus was one of those semi-apocryphal martyrs that sixteenth-century reformers loved to mock: supposedly a bishop in the third century, he was tortured by the bad guys in increasingly lurid ways. Most famously, he had his guts wound out on a windlass (as you can see in the miniature above). He was incredibly popular in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, especially in England and northern Europe.

Erasmus’s Middle English Life is structurally odd; unlike the “life” (also called a vita) of most saints, which tell the saint’s life and holy death as a narrative, the Life of Erasmus is more a litany of his tortures, a list of the benefits you can expect if you venerate him, and a string of prayers. Lots of listing, little storytelling. The Life is also unusual for the emphasis it puts on Sunday: because Erasmus endured all his torments and did all his good deeds as a bishop on Sundays, you devout medieval Christian should also do your good deeds on Sundays instead of (the subtext hints) working or going fishing.

This Sunday element seemed to be distinctive to the Middle English version of his life. As far as I can tell, the Latin versions of his life didn’t include anything about Sunday.* This is especially true of the most widely circulated Latin life, which appears in Jacobus de Voragine’s Latin collection of saints’ lives, the Legenda Aurea. Interestingly, the late fifteenth-century English translation of the Legenda Aurea (by the printer William Caxton)** does include several references to Sunday. On the other hand, the French, German, and Spanish translations either don’t include Erasmus or, if Erasmus shows up, Sunday doesn’t.

So I seemed to have the association of Erasmus and Sunday as a distinctively English phenomenon. Awesome, and a Fun Fact upon which to build my article’s argument.

The other thing to know about the Middle English Life of Erasmus is that it was quite popular. It appears whole in four manuscripts, and its prologue alone shows up in two more – that’s a decent showing for a Middle English poem probably not composed before 1400. Its prologue also appears, highly abbreviated, as a caption to a wall painting of Erasmus’s tortures in the parish church of Cirencester, England. (If I’m getting my church geography right, it would have been visible through the stone screen, on the left side of this picture. It’s mostly effaced now, so thanks must go to nineteenth-century antiquarians for copying it down while it could still be seen.)

This photo of Parish Church of St John Baptist in Cirencester is courtesy of TripAdvisor

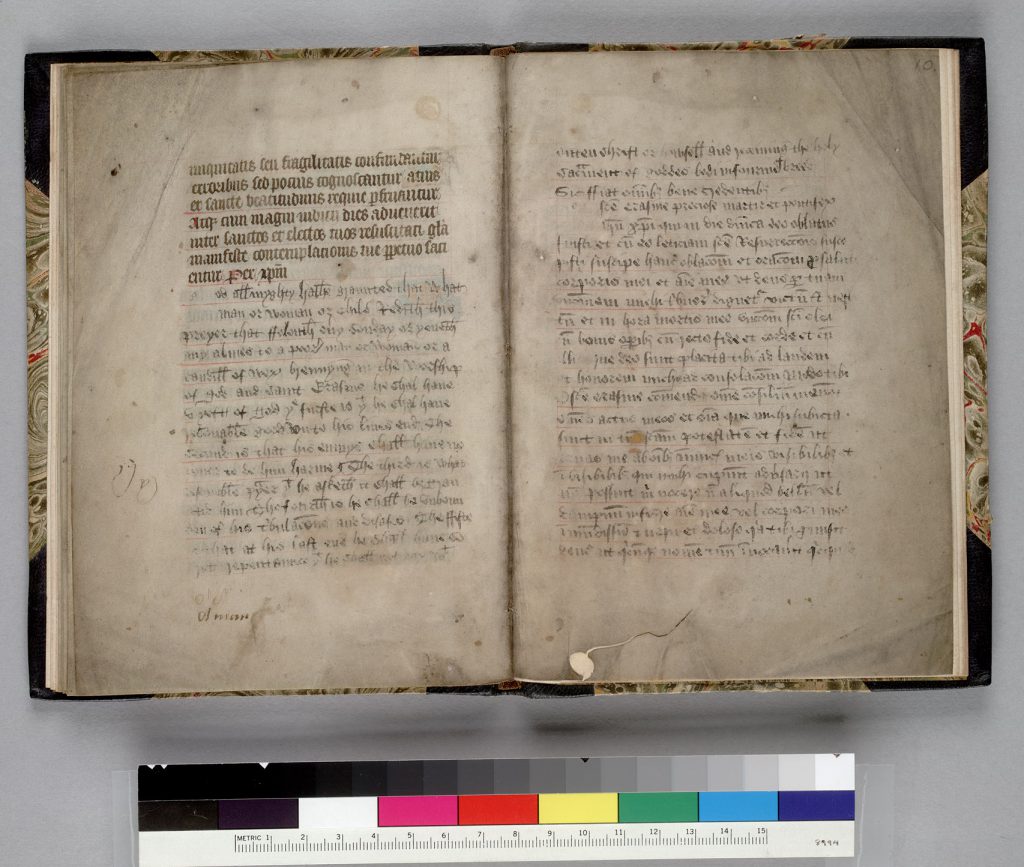

I knew about these seven versions of the Life before I started writing my article, but only when it was fully drafted did the Magic Of The Internets throw up an eighth version: another highly abbreviated version of the prologue, written out as prose, as an introduction to a suffrage for Erasmus in a Book of Hours: Huntington Library, MS HM 1159, fol. 9v-10v. It states that anyone who reads the following prayer each Sunday, or gives alms, or donates candles to the church in Erasmus’s honor, that person will get five gifts from God: sufficient possessions, freedom from enemies, answers to reasonable prayers, good health, and a good death.

(Note how a later owner has added it to his or her Book of Hours; this is also true of two of the other Middle English lives, which were written by later owners on their manuscripts’ endpapers. People loved it so much that they just had to have it.)

So that was a nifty confirmation of how popular this story was.

Later, I found a second instance of the Middle English prologue being used in front of a suffrage: that’s in Pierpont Morgan, MS M.487, fols. 215r-v (details in Chichester Cathedral Prayerbook pp. 14-15). It accompanies the image that opens this post, so we know that a dapper young man named John used that prayer.

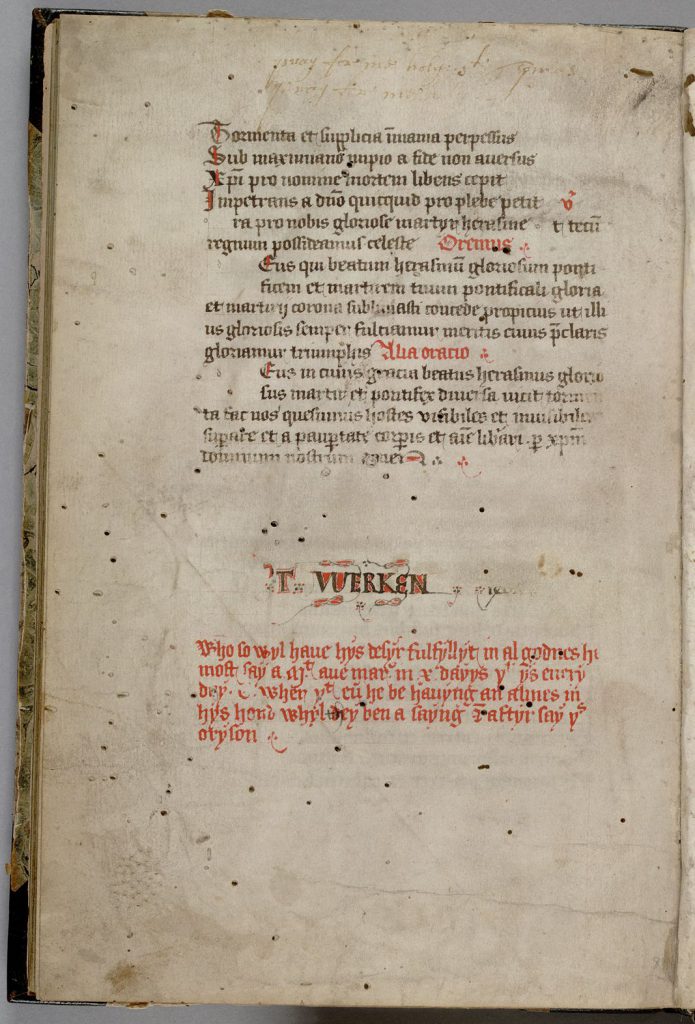

But wait. There were two more Books of Hours in the Huntington Library with prologues to their suffrages for Erasmus. This English one, from MS HM 142, fols. 59v-60v, has a Latin prologue stating that whoever will say this prayer every Sunday, or will give alms in honor of Erasmus, he’ll get whatever he asks God for.

Sorry, no image of the recto with the prologue, but here’s the verso with the end of the suffrage. Note how a sixteenth-century reader has written “Pray for me St Erasmus / Pray for me” in the top margin.

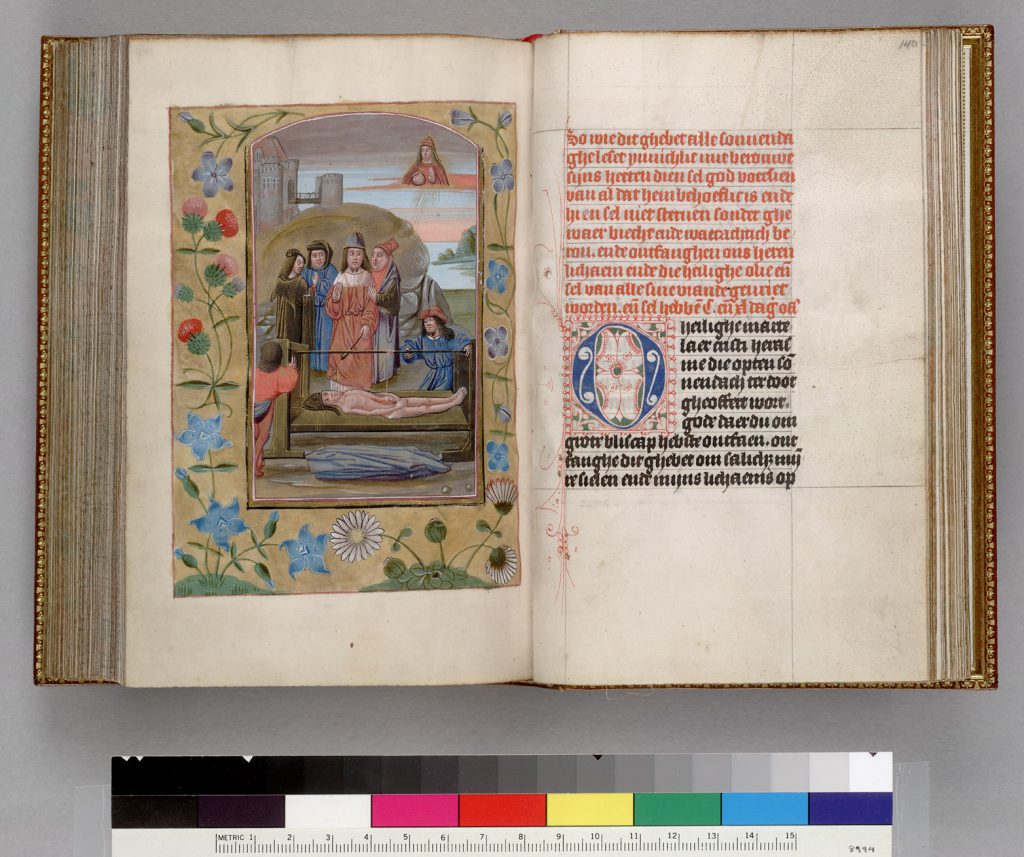

The third one is from MS HM 1140, starting on fol. 140r.

It’s in Dutch.

I don’t do Dutch.

But even my non-Dutch-reading eyes could see that the last word in the first line was “sonnendaghe”: Sunday.

So there I was, watching my theory about the English cult of Erasmus and Sunday fly out the window. And I couldn’t read the damned thing to figure out how many holes that rubric had just blown in my article.

Here comes the generous collaboration part of my story. Thanks to the goodness that is #medievaltwitter and the graciousness of many individuals there, Dr. Rabia Gregory of the University of Missouri helped me out with a transcription and a rough translation. To summarize, the indulgence says that anyone who says the accompanying prayer while really meaning it, that person will get what they need from God, won’t die unshriven, and will get 160 days off their purgatory sentence.

This indulgence text is a little different than what I was finding in the Middle English lives. Although it accords in its “prayers answered” and “good death” clauses (which are common in suffrages), it doesn’t include specific acts of mercy, like the giving of alms or candles. Moreover, the Middle English texts never have indulgences attached. Still, if Erasmus could go with Sunday in a Dutch indulgence, clearly I needed to stop assuming that the narrative stories of his life were the only place to look for textual precedents for my Middle English Life. So I started doing what I should have done months ago: I started looking at the suffrages in Books of Hours.

And that’s where teaching this series of classes has made me better at my job. (Only belatedly, I admit, but I got there eventually.) Once I had my tools — the databases of digitized manuscripts, practice navigating the structure of Books of Hours, and the experience of skimming Latin prayers — this kind of research is pretty straightforward. It was the work of a couple of afternoons to hunt down a representative sample of Erasmus suffrages. A major shout-out goes to Jessica Roberts from last fall’s Hargrett Hours class who helped with the research. There’s another plot point in the “generous collaboration” storyline.

So what did I learn from those afternoons of peering at Gothic script on my computer screen? Several provocative pieces of data emerged:

- – Suffrages for Erasmus rarely appear in French Books of Hours, and never in Italian or Spanish prayerbooks (although admittedly fewer of those have been digitized in the collections I was using).

- – Suffrages for Erasmus frequently appear in Dutch, German, and English Books of Hours.

- – Most of the time (about 80%, according to my list below), these suffrages do include some reference to Sunday, either in a rubric or prologue or, more commonly, in the suffrage itself.

(If you want to retrace my footsteps,*** I’ve put a list of all my confirmed Erasmus suffrages as an appendix, below.)

It turns out that suffrages for Erasmus are frequently quite long. In many Books of Hours, suffrages are short enough to fit tidily on the front and back of a single folio. But Erasmus’s suffrages can go on for pages and pages — and when they do, they almost always open with the phrase, “Sancte erasme, preciose martir et pontifex christi, qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisti…” (Saint Erasmus, precious martyr and bishop of Christ, you who were offered [as a martyr] to God on the day of the Lord…)*4* These long suffrages can differ quite substantially after the opening lines, but they consistently assert that Erasmus died on a Sunday and/or (in the prologues) that prayers said to Erasmus on Sundays are efficacious.

Which are exactly the two points that my Middle English Life of Erasmus develops.

Fortunately for my sanity, this new data didn’t derail my article; the Middle English poem is doing more elaborate things with its Sunday leitmotif than are the suffrages, and the fact that the Sunday theme may not have originated with the English poem is not an argument killer. Still, this research hiccup was a much needed wake-up call. Lay your research’s groundwork in the devotional word, not just the literary one.

But this sudden proliferation of Erasmus-and-Sunday suffrages has produced, hydra-like, a bundle of new, as-yet-unwritten stories.

The first is the story of suffrages and mouvance. (Don’t know what mouvance is? Here’s the best explanation I’ve ever found.) I haven’t been doing a close textual comparison of these Erasmus suffrages that open with the Sunday clause, but I’m confident that few of them are the same. Let me repeat that. Most of the eighteen “in die dominico” suffrages in my list below appear to be different in substance (not just minor scribal shifts) from the others. That’s a lot of mouvance. That’s a lot of scribes exerting authority over people’s devotions. Sometimes, I’m sure, the changes were instituted either by the person who ordered the manuscript or by her/his spiritual advisor. Even so, there’s a lot of variety in the way that medieval people invoked Erasmus, despite the consistent emphasis on his Sunday martyrdom.

The second is the chicken-and-egg story: which came first, the suffrages that link Erasmus to Sunday, or the Middle English Life of Erasmus’s insistence that Erasmus is a “Sunday Saint”? It’s impossible to tell. The earliest dated manuscript in my “Sunday suffrage” list is BL, MS Add. 50005, a Dutch horae (1410-1420); the earliest English one is the Hours of Eleanor of Worcester (BL MS Harley 1251, 1430-1440). When does the Middle English Life of Erasmus appear? Its earliest manuscript dates to the first quarter of the fifteenth century (Cambridge University Library MS Dd.1.1). So, according to the manuscript evidence I have so far, the suffrages and the Life show up on the scene at the same time, in England and northern Europe almost simultaneously. Many late medieval devotional trends originated in the Low Countries and migrated to England along trade routes; if I were opening a book on the question, I’d place odds on a Dutch origin. But I could be wrong. The earliest suffrage – at all – that I’ve found for Erasmus is English: Beinecke Library, MS Osborne a44 is an English horae that dates to 1390-1420 and contains a nifty verse Latin suffrage to Erasmus (but no Sunday reference). [UPDATE: Dr Kathleen Kennedy of Penn State Brandywine tells me that the Erasmus image in the Osborne manuscript is mid-fifteenth century, not early. Which increases the odds ever so slightly toward that Dutch devotional origin.]

Finally, there’s the unwritten story about the interaction between “literature” as we normally think of it and devotional Latin texts. The interdependency of these suffrages and the Life of Erasmus reveals the fluid exchange between prayer and poetry, the Middle English poetry sliding easily into prayer and the Latin prayers flowing off the tongue in a mellifluous stream. They differ in form more than in content, the poem functioning much like a lengthy prologue to a suffrage (as it is indeed used in Huntington MS HM 1159). And this is a realization I probably wouldn’t have come to had I not been teaching these courses.

Several years ago, Bruce Holsinger urged literary scholars to attend to the liturgy not just as an intertext for literary productions like the “Prioress’s Tale”*5* but also as a major ontological category. Any medieval believer who was more than passingly devout would have processed much of their world through liturgical structures, much as many of us today “think with” movie quotes and memes. It’s an unfamiliar leap to make, here in the twenty-first century, but if we don’t we’re missing much of these poems’ power and depth.

Notes

Works Cited

Agbabi, Patience. Telling Tales. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2014.

Camp, Cynthia Turner. “The Sunday Saint: Keeping a Holy ‘Merchant’s Time’ in the Middle English Life of Erasmus.” Saints as Intercessors between the Wealthy and the Divine: Art and Hagiography among the Merchant Classes. Ed. Emily D. Kelley and Cynthia Turner Camp. Routledge, forthcoming.

The Chichester Cathedral Prayer Book: Written and Illuminated in England by a Lancastrian Scribe and Artist during the Episcopate of Reginal Pecock (1450-1457). London, Chiswick Press, [1907].

“Erasmus.” Samlung Altenglischer Legenden. Ed. C. Horstmann. Heilbronn: Verlag von Gebr. Henninger, 1878. 198-203.

Holsinger, Bruce. “Liturgy.” Oxford Twenty-First Century Approaches to Literature: Middle English. Ed. Paul Strohm. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 295-314.

Appendix

All links go to manuscript descriptions; most manuscript descriptions link forward to digitized images. Note that this list only includes manuscripts that I have either looked at online or that have detailed enough manuscript descriptions to tell me what’s in a suffrage or rubric; I have identified the existence of additional Erasmus suffrages that I have not yet examined. And of course the results are skewed toward high status manuscripts of art historical value, since those are more frequently digitized. I welcome any additions and/or corrections.

Erasmus suffrages that mention Sunday, in the prologue/rubric or within the text itself

- 1. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.163, fols. 147r-149r. (Prayer Book of Bishop Leonhard von Laymingen of Passau) Passau, Germany, c. 1440. (A different version of the Long Suffrage that substitutes “die resurrectionis” for “in dei dominica”) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W163/description.html

- 2. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.202, fols. 39r-40v. England, 1460-70. (Long Suffrage for Erasmus that contains the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisti.”)

- 3. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.426, fols. 145v-52v. Bruges, c.1510-20. (German suffrage that seems to be related somehow to the “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisiti” version.) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W439/description.html

- 4. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.437, fols. 107r-108r (Aussem Hours). Cologne, early 16th c. (Seems to be a German version of the Long Suffrage? The opening rubric also seems to assert that this prayer is efficacious on Sundays.) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W437/description.html

- 5. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.439, 65v-70r (Hours of Adulph of Cleves). Ghent, 1480s. (Long Suffrage for Erasmus with the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisiti.”) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W439/description.html

- 6. Baltimore, Walters Art Musuem, MS W.918, fols. 190v-192r. Zwolle, Netherlands, c. 1470. (Dutch suffrage that seems similar to the Aussem Hours German-language suffrage.) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W918/description.html

- 7. Bensançon, BM, MS 155, f. 118v ff. Flanders, late 15/early 16c. (Flemish suffrage with “sondach”) http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/enlumine_fr?ACTION=RETROUVER&FIELD_1=REFD&VALUE_1=’Besan%E7on – BM – ms. 0155’&NUMBER=7&GRP=0&REQ=((‘Besan%E7on – BM – ms. 0155’) :REFD )&USRNAME=nobody&USRPWD=4$4P&SPEC=9&SYN=1&IMLY=&MAX1=1&MAX2=100&MAX3=100&DOM=All

- 8. London, British Library, MS Add. 50005, f. 159v-161v. Utrecht?, 1410-20. (Dutch version of the Long Suffrage?) http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_50005&index=0

- 9. London, British Library, MS Harley 1251 (Hours of Eleanor of Worcester), f. 33vff. England, made in Rouen, 1430-1440. (Version of the Long Suffrage that contains the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisti.”) http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=6646&CollID=8&NStart=1251

- 10. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS G.39 recto (prayer roll). Yorkshire, c. 1500. (Suffrage opens with the phrase “qui die dominico oblatus fuisti.”) http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=336970

- 11. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.487, fol. 214vff. Winchester for Chicester, 1490s. With miniature of owner venerating Erasmus’s martyrdom scene (Middle English prologue attached to a Latin suffrage that I have not yet examined. Prologue: Prayer said on Sundays is efficacious.)

http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=252014

- 12. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.1175, fol. 187v ff. Bruges, Belgium, 1525-30. (Suffrage opens with the phrase “qui die dominico oblatus fuisti.”) http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=355473

- 13. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.917/945 (Hours of Catherine of Cleves), pp. 258ff. Utrecht, Netherlands, c. 1440. (Suffrage opens with the phrase “qui die dominico oblatus fuisti.”) http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=335694

- 14. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS S.1, fol. 118r ff (Book of Hours in Geert Grote’s Dutch translation). Utrecht, Netherlands, c. 1490. (Dutch suffrage with opening rubric, not identical to the indulgence in Huntington MS HM 1140. Suffrage itself does include “sonnedach,” but seems not to be identical with HM 1140’s suffrage.) http://corsair.themorgan.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=325774

- 15. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, MS codex 1063, fols. 109r-110v. England, c. 1450-1460. (Long suffrage version with the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisiti.”) http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/medren/pageturn.html?q=%22book%20of%20hours%22&id=MEDREN_4154279&

- 16. San Marino, Huntington Library, HM 1140, fols. 140v-141v. Netherlands, end of 15th c. (Dutch indulgence attached to a Dutch suffrage. Prayer said on Sundays is efficacious.) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/digitalscriptorium/huntington/HM1140.html

- 17. San Marino, Huntington Library, HM 1159, fols. 9v-10v. England, early 15th c with late 15th c additions. (Middle English prologue attached to a Latin suffrage that includes the “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisiti” phrase. Prologue: Prayer said on Sundays is efficacious.) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/digitalscriptorium/huntington/HM1159.html

- 18. San Marino, Huntington Library, HM 142, fols. 59v-60v. England, c. 1467. (Latin prologue attached to a Latin suffrage. Prayer said on Sundays is efficacious.) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/digitalscriptorium/huntington/HM142.html

- 19. San Marino, Huntington Library, MS HM 1249, within the range ff. 117-136. Netherlands, second half 15c. (Suffrage opens with the phrase “qui die dominico oblatus fuisti.”) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/digitalscriptorium/huntington/HM1249.html

- 20. The Hague, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, MS 131 G 4, fol. 166v-169r. Utrecht, c. 1470. (Dutch version of the Long Suffrage?) http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/131+G+4

- 21. The Hague, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, MS 135 G 19, fol. 140v-141v. Northern Netherlands (use of Utrecht), c. 1495. (Shortened version of the Long Suffrage that contains the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisti.)” http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/135+G+19

- 22. The Hague, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, MS 135 J 10, fol. 124r-125v. Bruges (Use of Rome), 1480-90. (Shortened version of the Long Suffrage that contains the phrase “qui in die dominico deo oblatus fuisti.)” http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/135+J+10

- 23. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS liturg. 184, fol. 15vff. England, 1425-50. (Long Suffrage with the “die dominico” opening) http://bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk:8180/luna/servlet/detail/ODLodl~1~1~3850~103986?qvq=q:Shelfmark=%22MS.+Liturg.+184%22;sort:Shelfmark,Folio_Page;lc:ODLodl~29~29,ODLodl~7~7,ODLodl~6~6,ODLodl~14~14,ODLodl~8~8,ODLodl~23~23,ODLodl~1~1,ODLodl~24~24&mi=1&trs=7 Courtesy of Dr Kathleen Kennedy.

- 1. Baltimore, Walters Art Museum, MS W.432, fols. 15v-16r. Leiden, Netherlands, early 16th c. (Dutch suffrage, short) http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W432/description.html

- 2. London, British Library, MS Add. 547825, f. 154r-v (Hastings Hours). English use but made in Ghent or Bruges, c. 1480. (Latin suffrage, short) http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_54782

- 3. New Haven, Yale University, Beinecke Library MS Osborne a44, fols. 11v-12r. England, 1390-1420; Erasmus sufferage probably mid 15th c. Contains a verse Latin suffrage that foregrounds Erasmus’s tortures, but makes no mention of Sunday. http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3729204

- 4. Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS ms lat. 10533, f. 139r-v. Metz, France, 15th c. (Short Latin suffrage) http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10318624f/f282.double.r=ms%20lat%2010533

- 5. The Hague, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, MS 74 G 35, fol. 95r-v. Use of Utrecht, Delft (southern Netherlands), 1440-1460. (Short Latin suffrage) http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/74+G+35

- 6. The Hague, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, MS 76 G 9, fol. 130v-131v. Netherlands, c. 1490. (Dutch language, no reference to Sunday AFAICT) http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/manuscript/76+G+9