It’s relieving when things start to fall into place.

Up until now, the research I’ve been working on has felt like the beginning of a television crime drama. Everything I know is pinned to a wall, with some red string connecting bits here and there, but the gritty details that’ll solve the case haven’t been fully uncovered.

Currently, the red string consists of the Passion narrative and Sainte-Chapelle. During Fall 2016, Group 1 of ENGL 4230 discovered an incredibly specific feast day in the calendar, one which celebrates the Translation of Saint Louis’ Head to Sainte-Chapelle; Sainte-Chapelle was built by Saint Louis, King of France from 1226 to his death in 1270, to house his collection of Passion relics. The office, scripture, and prayers that dominate the Hargrett Hours focus on the Passion, connecting Hargrett’s Passion material to the chapel quite nicely.

Since my research focuses on Hargrett’s scripture and prayers, I haven’t had much of a reason to think about Sainte-Chapelle. I’ve been focused on recording instances of Hargrett’s text in a terrifying spreadsheet, and while doing so I forgot to record the rubrics that precede many of the prayers I had found. I realized this halfway through the semester, so after a brief panic, I went back through the table and recorded what I had missed. After doing so, my red string took the form of a string of red text.

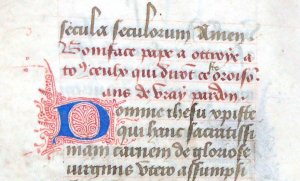

A few small words in those rubrics link one of Hargrett’s prayers to Sainte-Chapelle in an interesting way. Prayer 6 (Domine ihesu xpiste | qui hanc sacratissimam carnem…) in the Hargrett Hours includes the rubric Boniface pape a ottroye a to(us)| (con)ceulx qui dirot ce(ste) oroiso(n)| ans de vray pardon. While my Middle French isn’t exactly strong, the two bits that stick out are “Boniface pape” and “ans de vray pardon,” essentially meaning Pope Boniface indulgenced this prayer.

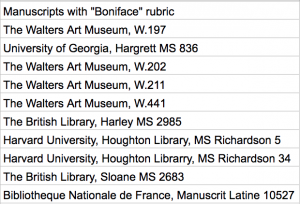

Boniface appears in a number of other rubrics attatched to Prayer 6, some of which indicate Pope Boniface VI. In the survey I’m conducting with Madison, six out of thirteen instances of Prayer 6 include “Boniface papa VI” in conjunction with “Philippi regis Francie.” One references Boniface alone, and the other six either indicate the prayer with a simple “oratio” or only reference when the prayer should be said, during the Elevation. Although there are nine Popes Boniface and six Kings Philippe, only Boniface appears specifically, as Boniface VI, in the rubrics. This is odd, for a number of reasons.

Boniface VI’s pontificate was only fifteen days long, held during April of 896. At the end of those fifteen days, he either died of gout, or was killed Stephen VI, who became pope following Boniface’s death. Fifteen days is an incredibly short amount of time to confer with a King of France from Rome, especially if the matter at hand is just a prayer. Boniface VI couldn’t have been in contact with King Philippe, though, because King Philippe I wouldn’t be born until 1052, 156 years after Pope Boniface VI died.

So, to understand why these prayers reference a short-lived Pope and King Philippe, you need to know a small bit of history concerning France and the Papacy.

At the end of the 13th century, France was at war with England. King Philippe IV and King Edward I taxed their respective clergies to support the effort, and did so without the permission of Rome. The Fourth Lateran Council, held in 1215, expressly forbade lay rulers from taxing the Church without the Pope’s permission; doing so was a challenge to the Pope’s authority. It happened occasionally, usually during military campaigns, but Philippe and Edward happened to bend the rules during the reign of Boniface VIII.

Boniface VIII was either a power-hungry or misunderstood Pope, depending on whether you read from secular or ecclesiastical sources. He confirmed the highly controversial resignation of Pope Celestine V, and then had the old man confined to the castle of Fumone, where Celestine died a month later (amidst rumors that Boniface VIII had him killed, since Celestine’s presence was a threat to his own status as Pope). Boniface was incredibly sure of his own power, and saw it fit to issue the bull “Clericos Laicos” in 1296 to condemn England and France for taxing the clergy; the bull stated that Kings did not have absolute authority over everything in their realms, namely ecclesiastical goods and persons, and ultimately, and that anyone who did so without the Pope’s permission faced excommunication.

In any other time, “Clericos Laicos” would have been an effective way to cease unwanted action from the French crown. However, France in 1296 was well on its way to becoming a powerful nation, a force to be reckoned with. King Philippe IV knew this, and so in response to “Clericos Laicos” he cut off every stream of revenue from France to Rome. The papacy relied heavily on currency sent from France, and Boniface held out as long as he could with the paltry income that was left, too proud to admit defeat. However, in February of 1297, just barely scraping by, Boniface’s pride was defeated by his empty wallet and he “granted” the French crown permission to tax the clergy under special circumstances. Philippe, victorious, allowed the Church to resume taking French revenue.

After the first dispute, things were calm between France and the Pope. In 1297, Boniface canonized King Louis IX, Philippe’s grandfather and the man who built Sainte-Chapelle. The reconciliation lasted until 1301, when Philippe IV decided again to test his power against the papacy.

The special privileges granted to France by the Pope in 1297 demonstrated the power of a secular king over the Pope. Since Rome relied heavily on ecclesiastical income from France, Boniface recognized that bending slightly was necessary. However, in 1301 Philippe arrested a French prelate without the Pope’s consent. He then wrote to Boniface, listing a number of crimes he insists the prelate committed, and asked the Pope to sanction his execution. Boniface, furious that Philippe had dared to arrest the prelate in the first place, refused, and began issuing bulls rescinding France’s spiritual privileges and reinforcing his own spiritual authority, all of which Philippe replied to dismissively, until “Unam Sanctam.” Boniface’s final bull.

“Unum Sanctam” stressed the importance of the Pope’s spiritual power over the King’s temporal power, ultimately saying that Philippe was not the sovereign ruler of France, but still beholden to the papal office. At that time, Boniface also began proceedings to excommunicate King Philippe IV from the church, a move which would severely undercut Philippe’s power. So, Philippe sent a team of his men to Rome to capture Boniface. Pope Boniface VIII died a month later, but there remains doubt about whether he was murdered by Philippe’s men or killed by the shock of being captured.

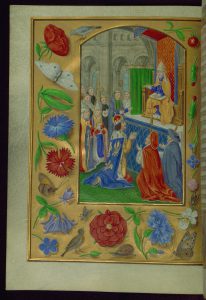

The story boils down to this: a growing nation challenged the Pope’s power, and won. By replacing Pope Boniface VIII with Pope Boniface VI, the rubrics both rewrite and erase the history between Boniface and Philippe. Boniface VI’s presence creates a harmless facsimile of events that is far less dangerous to the Church’s power, a positive footnote and accompanying prayer rather than an bit of history. In order to rewrite the conflict, Walters W.441 even goes so far to include a miniature that depicts King Philippe on his knees before Pope Boniface, who sits above him on a dais; the shift in power is obvious. Boniface, VI or VIII, no longer appears to be a fallen man, but rather the savior of fallen men. King Philippe is not a defiant king, but a willing supplicant to the Boniface’s authority.

Boniface’s connection to Saint Louis makes this subversive (and minuscule) detail important. What should we make of the inclusion of a prayer linked to the illusion of positive relations between the Church and France? What does that say about whomever commissioned the Hargrett Hours- did they only know about Boniface’s canonization of King Louis IX, or were they aware of the history between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philippe IV? There truly isn’t a good way to know.

What we do know, though, is that the Hargrett Hours has another, albeit small, link to Sainte-Chapelle through Boniface and Saint Louis and France. Though prayer six only gives us “bonifacie papa” to work with, it’s still a step towards a greater understanding of Hargrett MS 836. After a year of study devoted to Hargrett’s scripture and prayers, it’s certainly something I was thankful for last Thursday.

-Katie

References:

Boase, Thomas Sherrer Ross. Boniface VIII. Constable & Co., 1933.

Gaposchkin, Cecilia M. The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 2008.

Strayer, Joseph R. The Reign of Philip the Fair. Princeton University Press, 1980.

Tierney, Brian. The Crisis of Church & State 1050-1300. Prentice-Hall, 1964.