When my Team Green-mates had already made the three biggest greens in medieval manuscripts—verdigris, malachite, and organic (plant) greens—it was time to think outside the box for our final pigment-making experiment. Luckily, it didn’t take much searching to find a green I had no idea existed but, as a fan of medieval painting, had seen hundreds of times before: green earth.

Green earth, sometimes called terra verte, has been around for as long as there’s been painting, but it found its claim to fame as the universal tone for underpainting flesh in the late medieval (and early Renaissance) era. Have you noticed how people in medieval paintings sometimes look a little… sick? If so, you’ve probably identified the tell-tale greyish-greenish hue of green earth peeking through. After the fragile pale pinks fade away, green earth emerges, revealing these as medieval era paintings.

That’s what I (Maggie, Team Green’s green earth extraordinaire) found so cool about this pigment: it’s not the most glamorous color, but its lasting visibility cues us into the unique practices of medieval artists and artisans in the modern day. So, even though it’s not as common in medieval manuscripts, it’s certainly a star player in the medieval decoration game and the history of art.

So, as we set on the journey of making green earth, consider it as such: an exploration of the spirit of medieval craftsmanship through an unexpected, but important, muddy green.

Getting Started

During the medieval era, making green earth was both simple and cheap. In fact, artisans have made ancient earth pigments like green earth for thousands of years by crushing a colorful mineral and washing it until a fine, saturated pigment powder remains. Green earth requires either glauconite or celadonite, two nearly identical iron-rich minerals found in deposits around Europe and the Mediterranean with both crystalline and stone forms.¹ For our experiment, we used celadonite stones, because our professor easily sourced them from the internet.

This all sounds pretty easy. It’s so easy, in fact, that most medieval craftsmen didn’t bother writing the process down. And finding a recipe wasn’t the only challenge green earth gave us. Celadonite is an unexpectedly hard mineral: according to Introduction to Manuscript Studies, it was often too “difficult to grind up fine enough to use for illumination.”² Whether we knew it or not (we didn’t–read your sources closely), we had our work set out for us, especially if we wished to test it on parchment.

After piecing together our own recipe from both medieval (shoutout Cennino Cennini for the lengthy Craftsman’s Handbook)³ and modern reconstructed sources,⁴ we finally began making our green earth.

The Recipe

First, we placed a small handful of celadonite rocks into a brass mortar and pestle to start grinding. Surprisingly enough, this was when we realized that choosing celadonite may have been, in fact, a mistake. The grinding process lasted the entire class period and persisted into a second: over two hours of just grinding! It was bleak, where malachite and verdigris had been so easy.

Remember what I was saying about experiencing medieval craftsmanship? As I sat baking under the hot Athens sun–an English major with a mortar and pestle in my hands, of all things, trying to crush a bunch of impossibly hard, tiny green rocks–I really started feeling it. I thought about how long it took to make only this one pigment, how laborious the work was, and then how colorful all of the manuscripts we had seen were. This was just one tiny step. My arms hurt, and a blister was forming by my thumb, but we bravely survived the sufferings of the illuminator!

Having reduced most of it to a powder, we picked out a few stubborn chunks and decided it was sufficiently ground.

Next, we “washed” the newly ground celadonite powder, a process meant to refine the material by lifting the finest, most colorful pieces out. We did this by transferring the powder into a smaller, porcelain mortar and pestle and then adding a bit of distilled water. Then, I slowly stirred up the finer particles by gently grinding with the pestle. Leaving just a few seconds to allow the heavy sediment to settle, I then poured the muddy liquid into a jar. We repeated this process until we had three jars full of water and celadonite powder. (Ideally, this process would be repeated until no sediment was left in the mortar, but after washing what we deemed a sufficient amount of powder, we ended the process for time.)

We waited a few minutes to allow all the sediment to separate and settle at the bottom before pouring out the water, leaving behind a dark, muddy green sludge. Our professor took the jars to evaporate between class periods, which turned the swampy sludge into a lighter, olive-y green powder that we brushed out into a small bowl. Finally, real pigment!

We waited a few minutes to allow all the sediment to separate and settle at the bottom before pouring out the water, leaving behind a dark, muddy green sludge. Our professor took the jars to evaporate between class periods, which turned the swampy sludge into a lighter, olive-y green powder that we brushed out into a small bowl. Finally, real pigment!

Turning pigment powder into something paintable just requires mixing with a binder. On our pigment-testing day, we added egg glair, the most common binder for illuminating medieval manuscripts made from whipped and separated egg whites. There was no exact measuring to this step; we just dropped in bits of glair and celadonite until the mixture reached a paint-like consistency.

Results

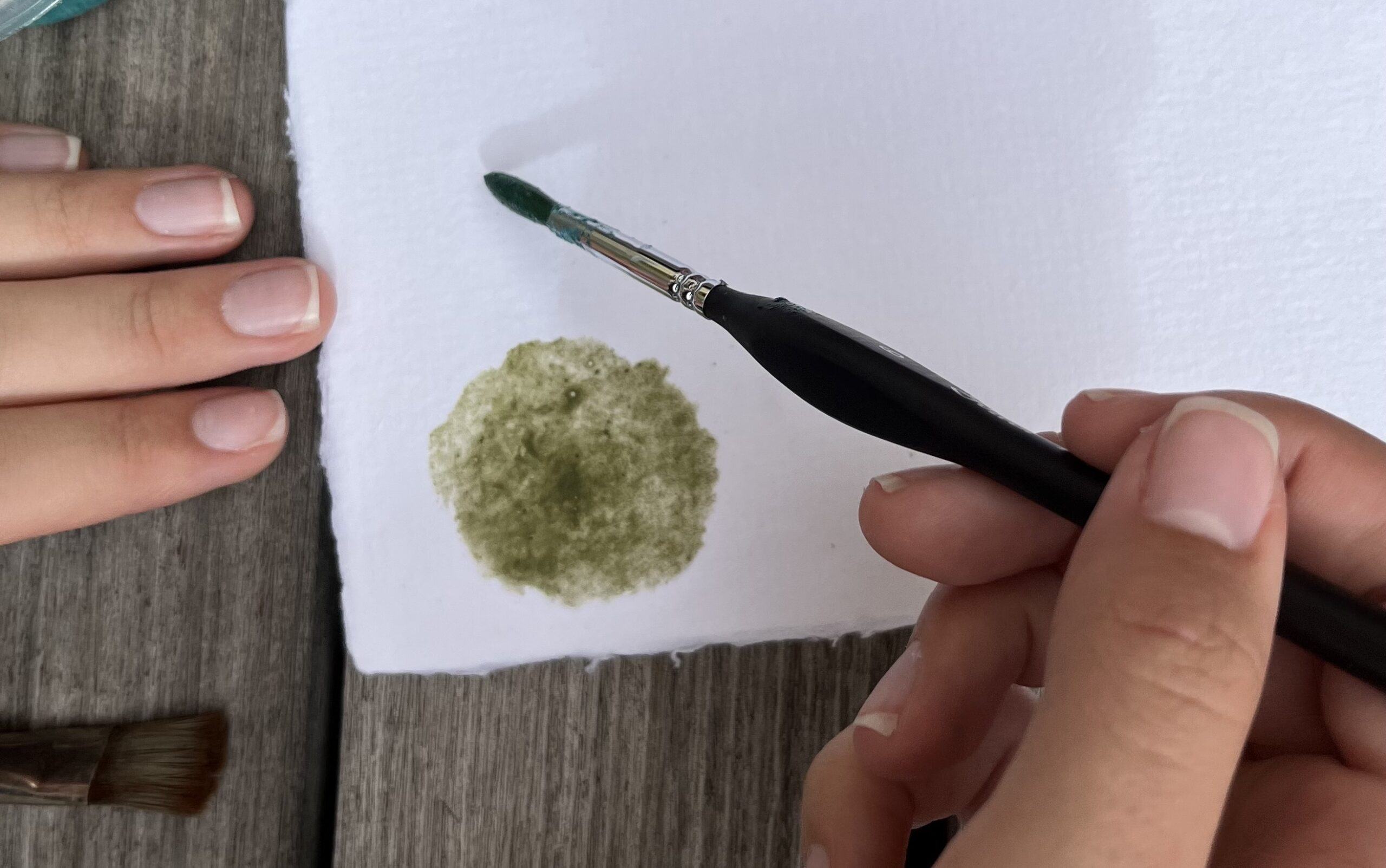

And thus, there it was! Green earth–and probably the most down-to-earth green earth ever. The color was as expected: a dull, natural olive green. The surprising part was its light consistency. Even after putting my heart and soul into the grinding, the celadonite particles were still too large to make a rich, dense paint, instead looking more like a watercolor.

Looking back, a few changes in process could have refined our grainy wash into real paint. First, the material: we could have swapped our celadonite stones for their crystalline counterpart, or even glauconite–anything that grinds finer. We also could have “mulled” the celadonite powder on a flat surface before mixing the paint, refining the pigment even further. Finally, we could have leaned more into its traditional context: instead of egg glair on parchment, egg yolk (which makes tempera paint) on panel might have done the trick.

Even though the paint wasn’t exactly what we expected, we still see our green earth pigment as a win for Team Green. Though it took a lot of time to make something that looks quite plain, following the steps of hundreds of generations of artists felt profound, making the whole process pretty exciting. And whenever one of us steps into an art museum, we’ll always be able to point out this subtle yet unmistakable piece of medieval history.

Footnotes

¹ Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. London, Archetype Books, 2003.

² Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2007.

³ Cennini, Cennino, and Daniel V. Thompson. The Craftsman’s Handbook: The Italian Il Libro Dell’arte. New York, Dover Publications, 1960.

⁴ Medlej, Joumana. Inks & Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology. Majouna, 2020.

⁴ WoodlandsTV. “Ancient Art: Making Earth Pigments.” YouTube, 18 Sept. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6k8JEEP0QNg. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

Credits

Author: Maggie Yarbrough

Featured image: student paints with green earth