Usually, if you want to look at manuscripts other than the ones your library holds, you need to hop into a car (or onto a plane) and go to them. But back in September, we were fortunate enough to have a cache of manuscripts come visit us. Dr Scott Gwara of the University of South Carolina is the mastermind behind their growing collection of medieval manuscripts; he is also a manuscript dealer running King Alfred’s Notebook, which specializes in items ideal for teaching collections. That means he’s got several manuscripts and many fragments in his possession at any given moment, so he kindly brought part of his collection to UGA for us to examine. Here are a few of the treasures we got to see.

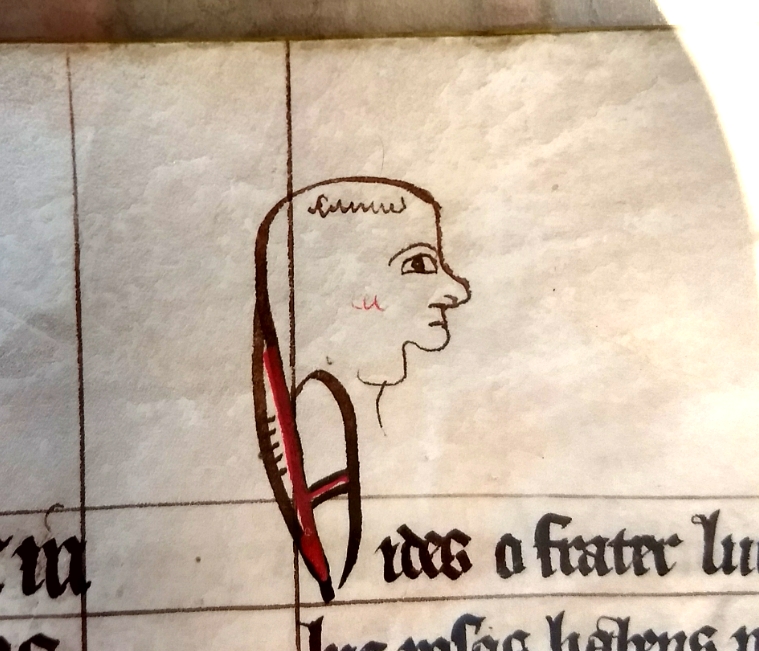

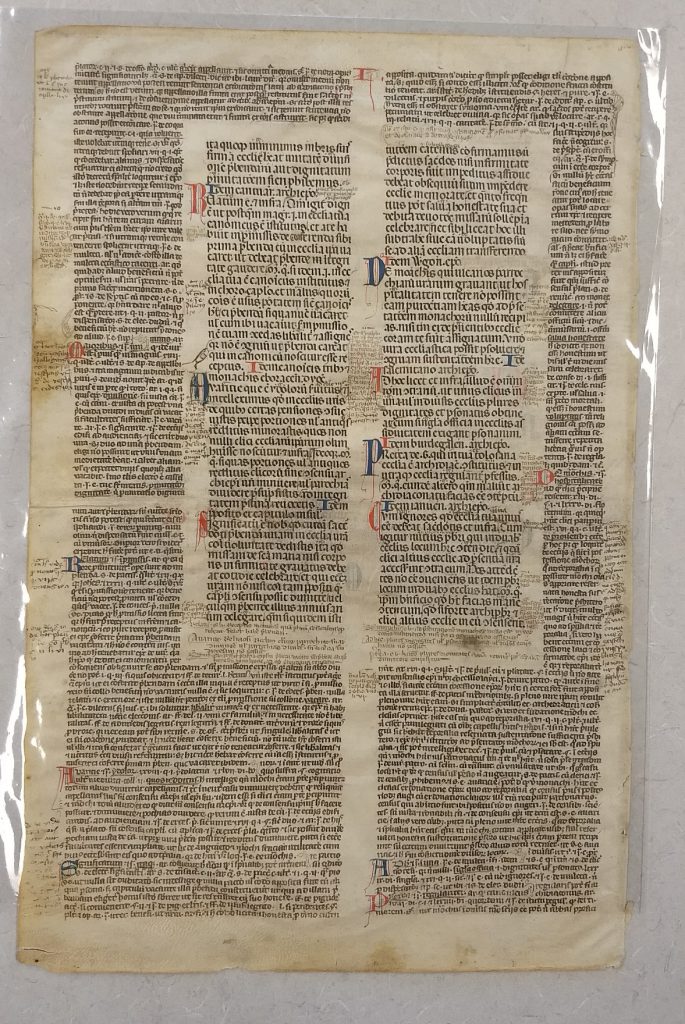

Dr. Gwara had several fragment examples of manuscripts laid out as glossed texts. The classic example of a glossed text is the Glossa Ordinaria, the standard explication of the Bible, but here we see a glossed version of a legal text, Justinian’s Digest (the standard collection of Roman law that still obtained in the medieval period). The text of the Digest is the larger script at the center of the two columns, while the interpretation of that legal treatise is arrayed in smaller script around the Digest text.

Look closely, and you’ll see yet a third level of text: later readers have added their own commentary on the commentary, between the lines. You can even distinguish between the different readers’ handwriting. (This manuscript is Italian, from the early thirteenth century.)

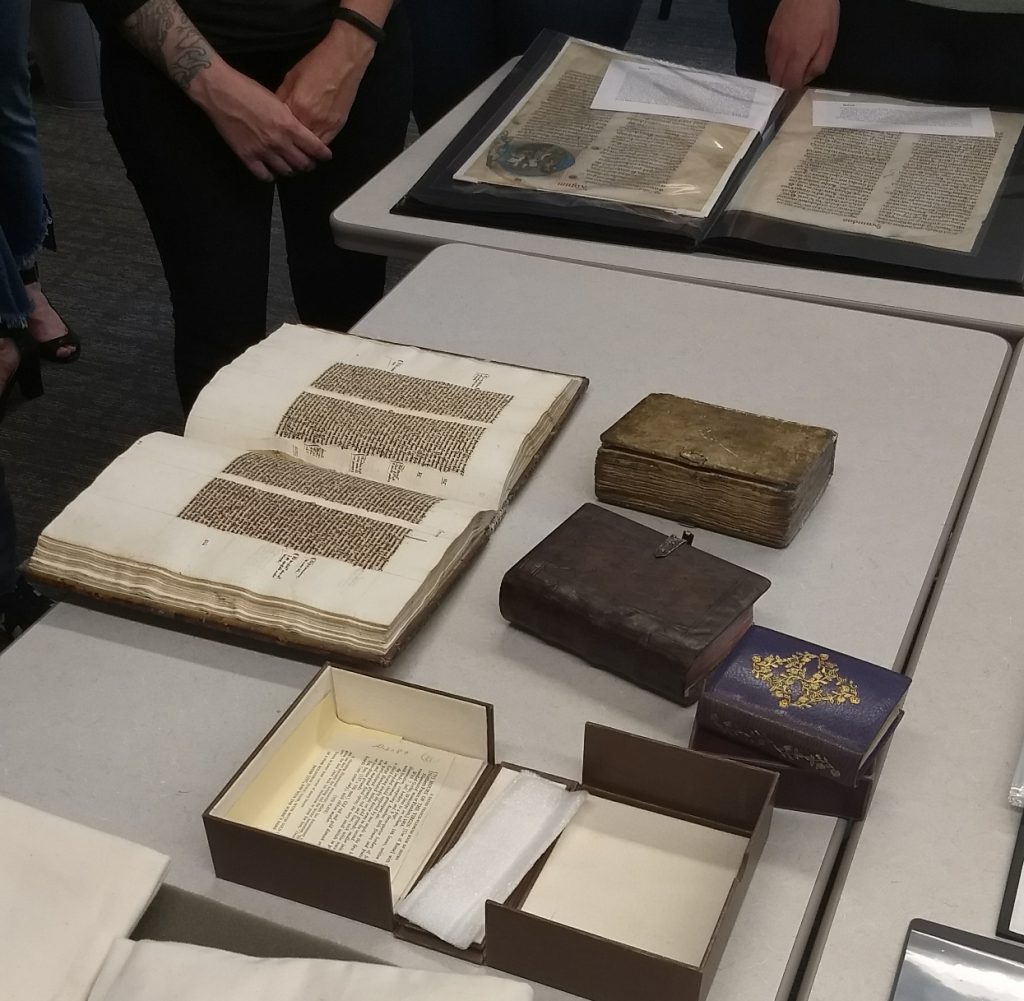

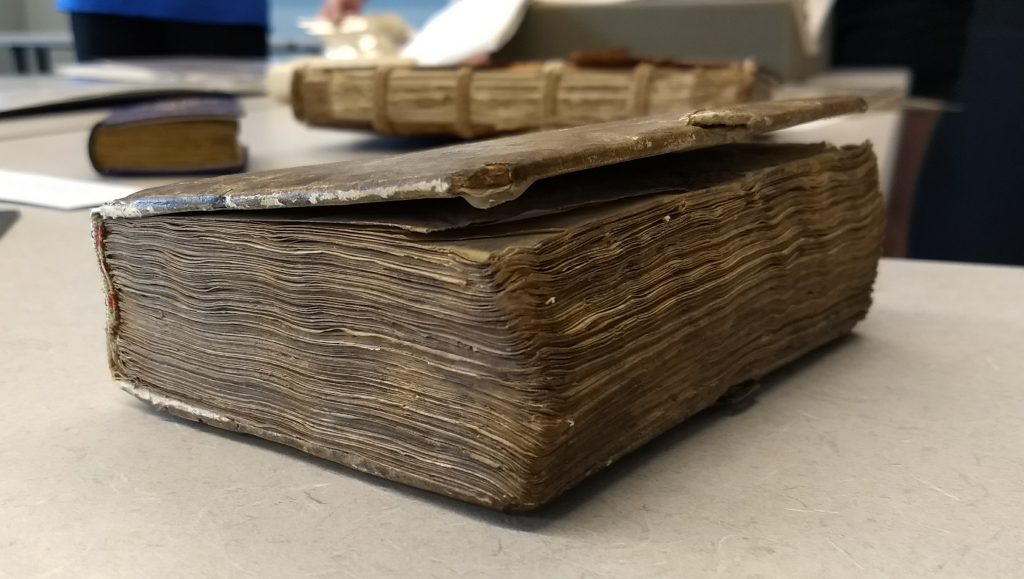

Even more exciting were the codices (bound books) in Dr. Gwara’s collection. Several were in their original bindings. This one is another thirteenth-century legal text. See how the pages are flush with the cover (the boards)?

That’s a feature of earlier bindings; whereas now we inset the pages (the text block) from the edges of the cover, to protect the edges of the pages, in the earlier medieval period they’d make cover and text block the same size.

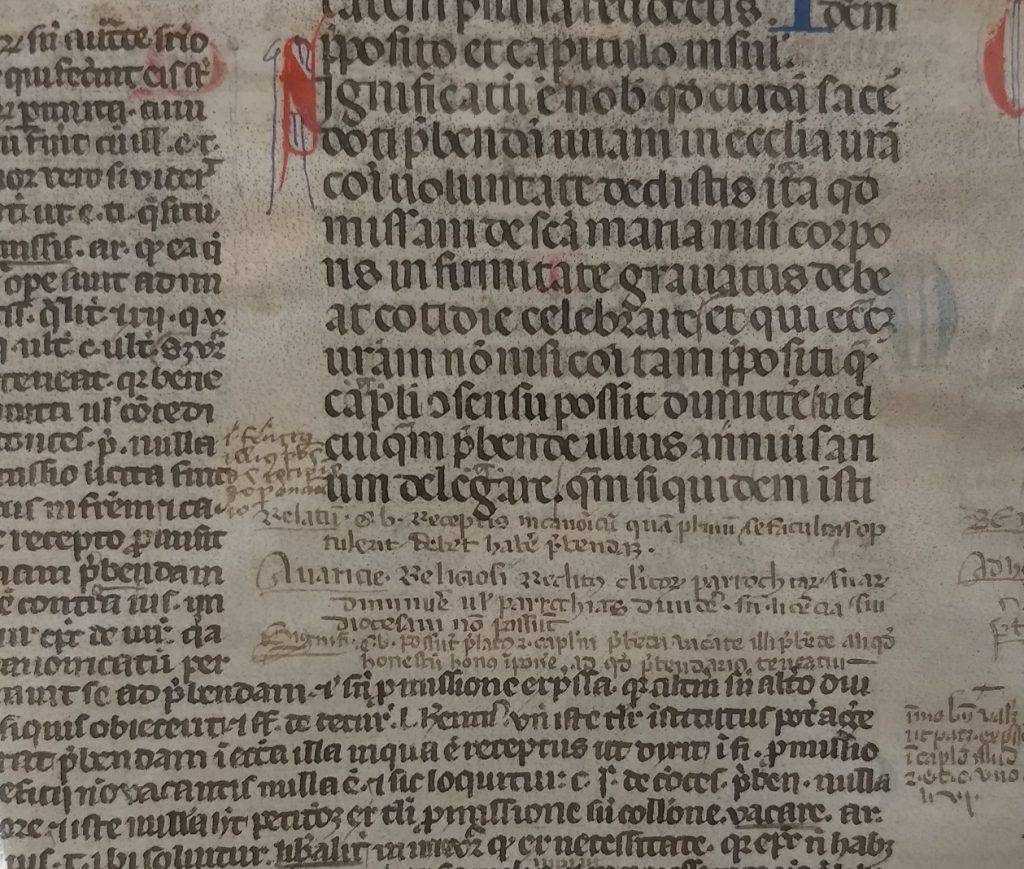

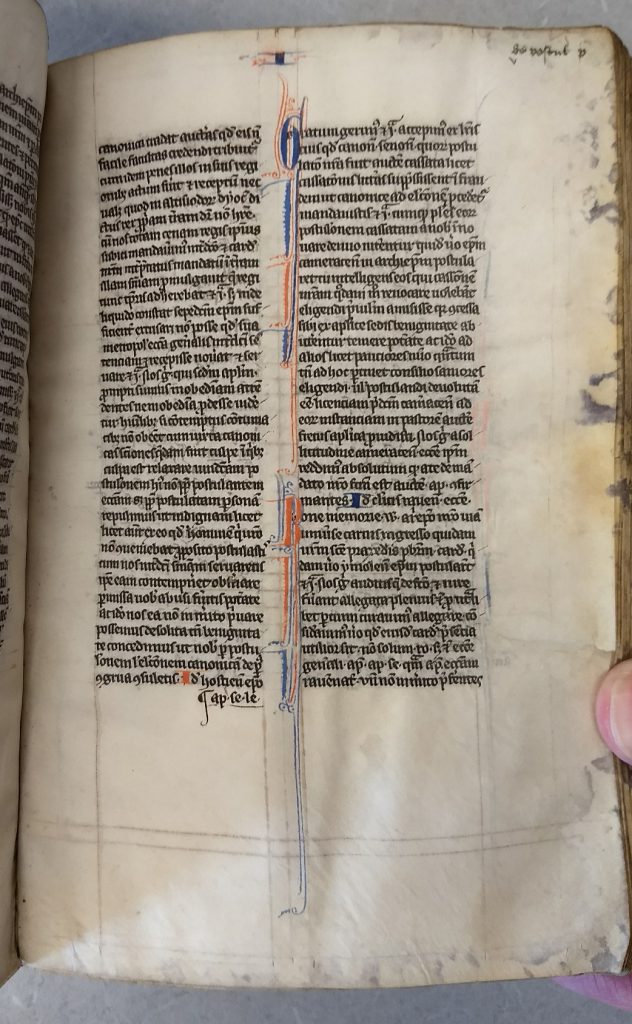

Here’s the legal text inside.

Looks a lot like a Bible, right, with the two columns of small script and the alternating red/blue decoration? It’s an example of how layout advances for one kind of lengthy, authoritative text (the Bible) influenced the layout of other long texts. You can see that the scribe has ruled extra columns (bounded with those double lines) in the outer and lower margins. Those columns are for the user to add his own glosses. The fact that those columns are blank, and that it has its original covers, suggests that (unlike the double-glossed fragment above) this volume was not used as heavily. Certainly it wasn’t read to pieces as some books were.

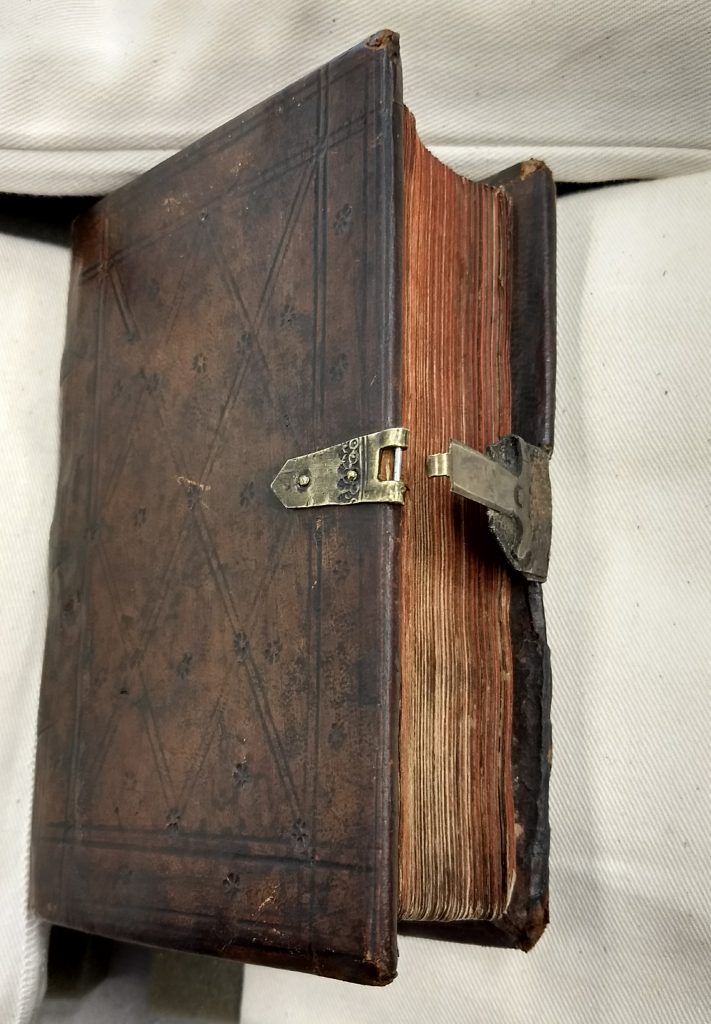

Another book that excited me was this fifteenth-century devotional book in German. The cover isn’t quite original – it’s been refurbished, but it still has its original wooden boards and metal fittings.

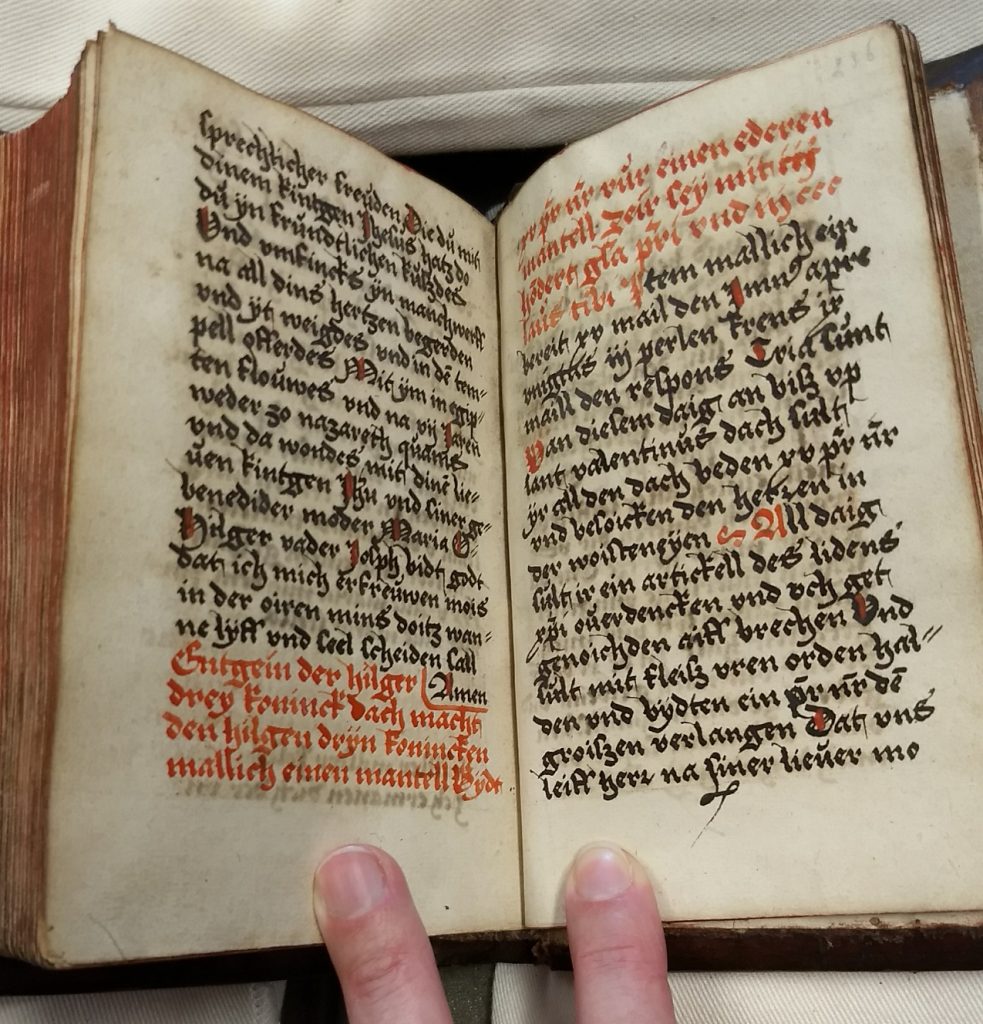

Inside, it contains devotional texts written in Old High German. Alas, I have no German, but Dr. Gwara said that the final pages include directions on how to make Baby Jesus a cradle and other nursery fittings through prayer, as part of a meditative spiritual exercise. If you’ve ever read the early fifteenth-century Book of Margery Kempe, a spiritual autobiography by a bourgeois English woman from East Anglia, you might remember her meditations early in the Book, when she imagines herself as Mary’s servant at the birth of Jesus:

And than went the creatur forth wyth owyr Lady to Bedlem and purchasyd hir herborwe every nyght wyth gret reverens, and owyr Lady was receyved wyth glad cher. Also sche beggyd owyr Lady fayr whyte clothys and kerchys for to swathyn in hir sone whan he wer born, and, whan Jhesu was born sche ordeyned beddyng for owyr Lady to lyg in wyth hir blyssed sone.

[And then the creature (i.e., Margery) went forth with Our Lady to Bethlehem and paid for her lodging every night reverently, and Our Lady was welcomed gladly. Also she begged for Our Lady some fair, white cloth and veils in order to swaddle her son when he was born. And, when Jesus was born she organized bedding for Our Lady to lie in with her blessed son. (The Book of Margery Kempe, ch. 6, lines 427-31)

This is the same kind of devotional imagination that the German prayerbook encourages: take the everyday, domestic thing you’re used to (taking care of infants, for most women) and translate that into a form of worship.

Someone with German can confirm for me whether this page contains those directions.

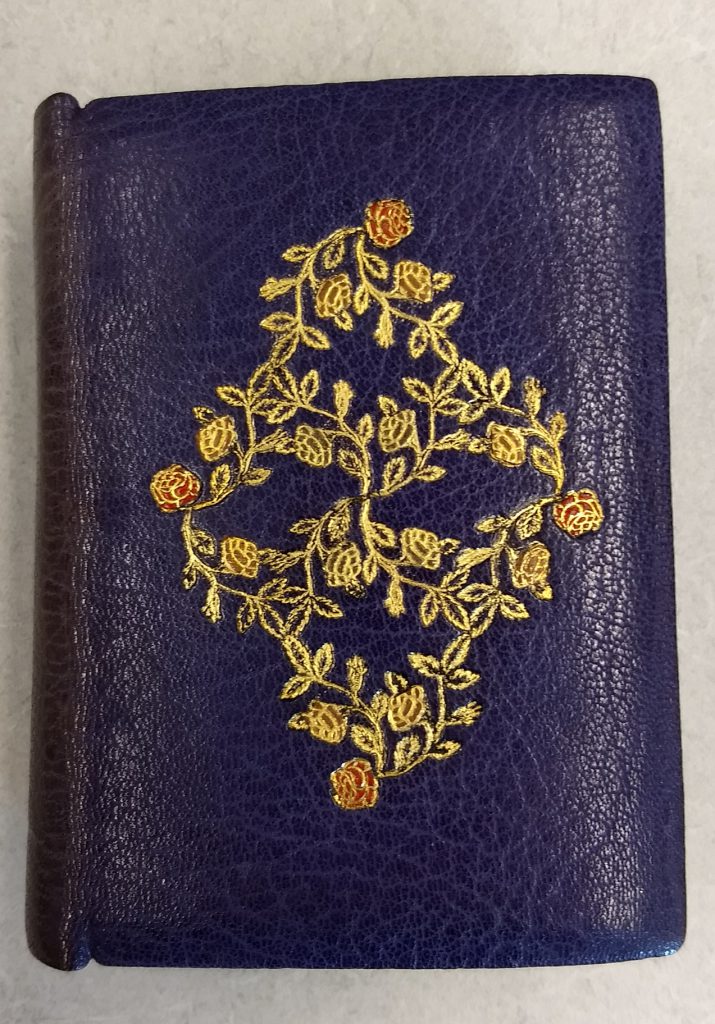

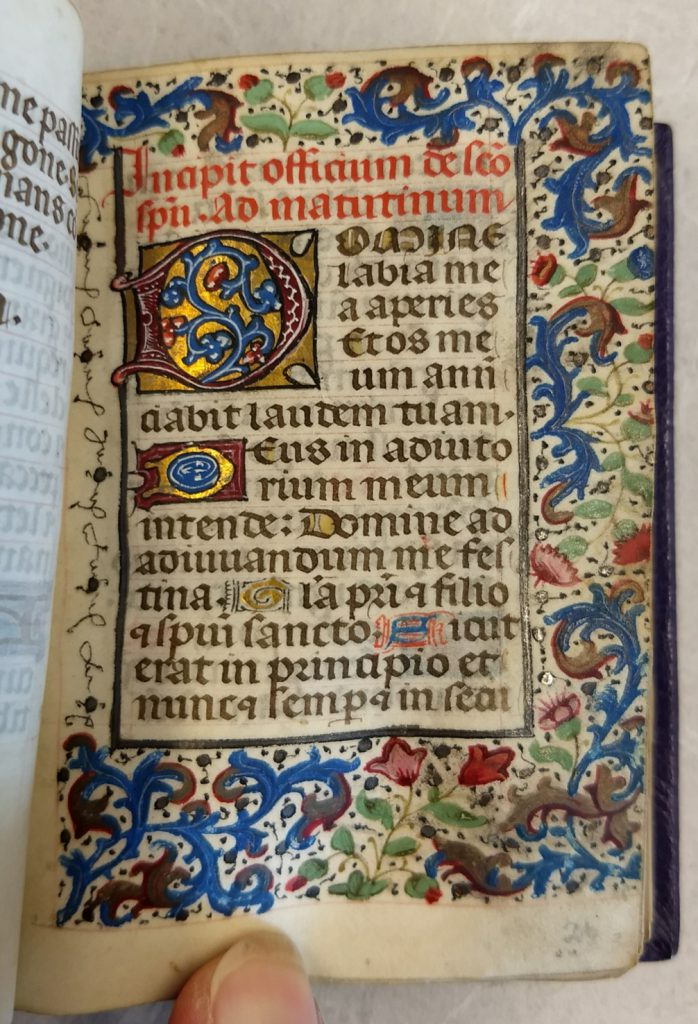

Finally, Dr. Gwara had this sweet little palm-sized Book of Hours. The cover is a bit LSU-meets-Victorian-kitsch, but its contents are lovely.

This book too was used, and used well. Its decoration is simple – no miniatures, only these bright gold initials and vibrant, thickly painted borders on key pages. Note the clarity of the script; it’s a rounded, Italianate form of Gothic that Dr. Gwara informed me was popular in mid-fifteenth-century Bruges (in the Low Countries) workshops. Note also the smudging of the borders on the top and bottom corners. All through the book, but especially on the border pages, the book’s use is visible in the dirt and rubbing of the paints.

(Thumb for scale. It’s a tiny book!)

Let me close with a big thank-you to Dr. Gwara for so generously sharing his time, expertise, and collection with us. It’s a rare treat to have such an array of manuscript examples to hand, let alone to have those examples travel to you. We’re all very grateful for the opportunity to play with Dr. Gwara’s collection.