By: Ashley Dolin, Georgia Earley, Luke Jordan, and Leah Sample

Why is an English class spending months laboring over a 15th century French manuscript? And why is a whole blog dedicated to it? This semester, Dr. Camp’s class has been focusing on inks and pigments, specifically in the Hargrett Hours. The Hours were tested using a pXRF machine, a portable x-ray device that allowed us to see which elements were present in any spot in the book. These spots were then translated into spectra, fancy science graphs, which could be used to determine which pigments were present. Our group was tasked with analyzing the text, including line fills and initials. We wanted to see if the pigments and inks used throughout the book were consistent, and we also wanted to know if they were consistent with other 15th century manuscripts. Pigments and inks can sometimes point a researcher to a specific area or time period, because certain techniques were popular at different times. In this blog post, we are going to dive into our discoveries and try to make sense of what we found.

Because we tested the actual text of the manuscript, the only colors we were considering were blue, black, and red.

Blue

We expected to find azurite in both the beginning and the end of the Hargrett Hours, in both the initials and line fills.

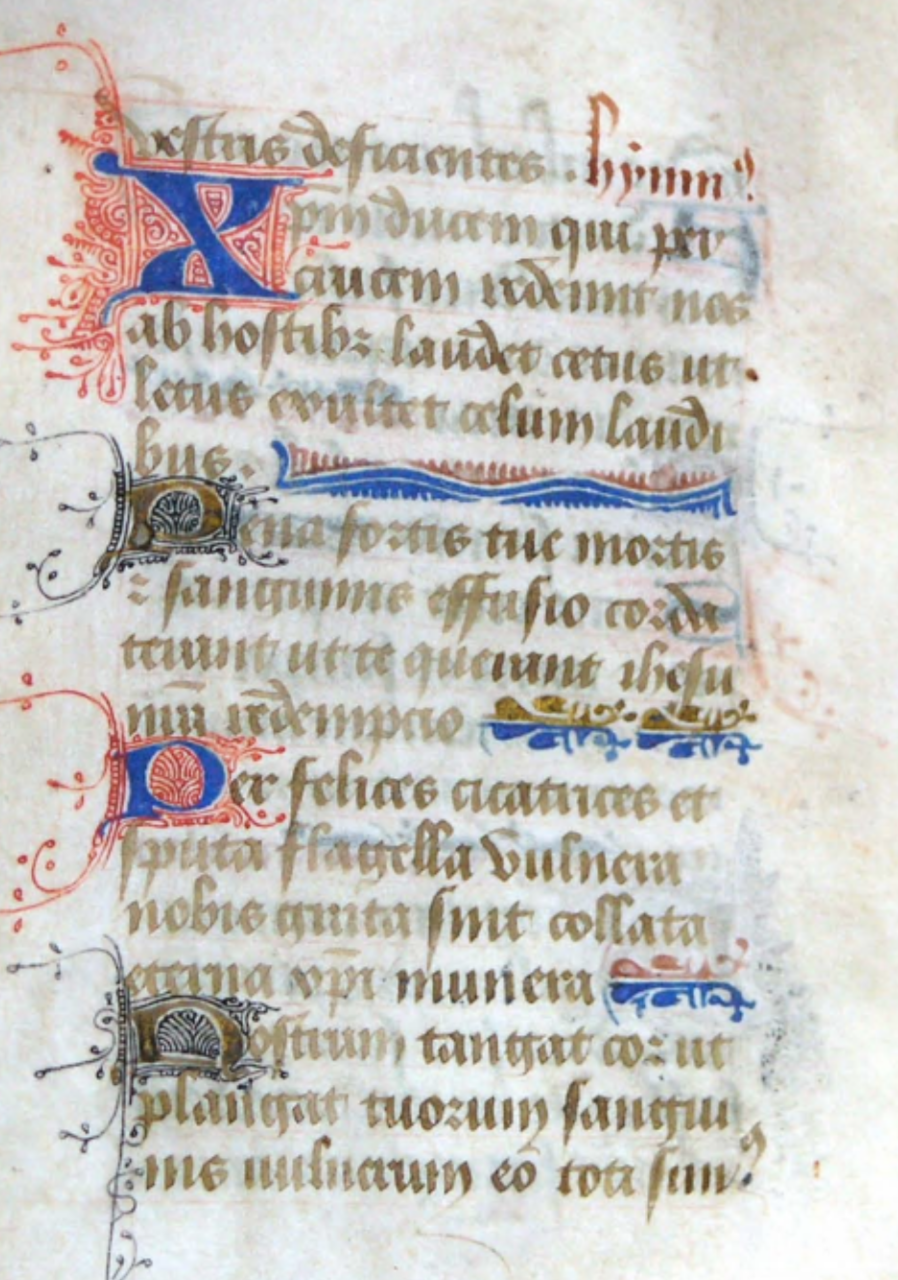

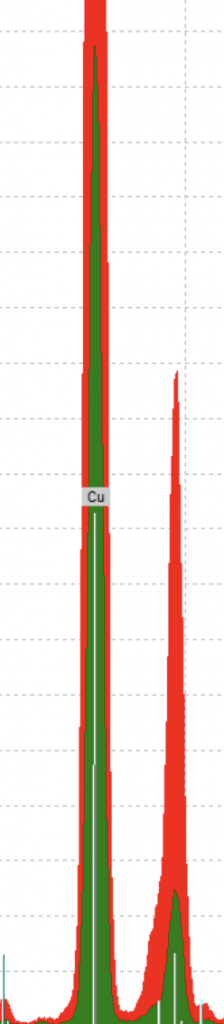

If that was the case, there would be a peak in Cu, copper, for both a sample from the beginning and at the end of the manuscript. That’s because azurite was the only blue pigment where we expected a big peak in copper. Without a significant copper peak, we might have been looking at an organic blue which would have made it very difficult to determine exactly which pigment it was. Elements that appear in organic substances are low on the periodic table, and therefore do not show up in tests with the pXRF machine. Look below at our spectra of two blue initials, one from the beginning of the book and one from the end. Pay careful attention to the copper peak. We found exactly what we were looking for.

The red portion of the image comes from a sample near the beginning of the manuscript and the green comes from the end. Notice how they both have a similar high copper peak? That supports our hypothesis that they are both azurite. It’s pretty amazing how just one element helped us determine our pigment.

Another area that contained blue was a line fill on 15v. It was a very clean spectra, and we were really only able to see copper, which comes from the azurite blue, similar to the spectra we saw from the initial.

This data was consistent with the other blue areas tested, and was what we expected to find. The red pigment in the line fill gave us no results, which was not entirely expected, but is not unheard of. Due to the lack of data, we believe that the red pigment in this line fill comes from an organic source. The only other data from this source was iron, which can be accounted for by the ink surrounding the test area, and also behind it on 15v. Read more about the black and red inks below.

Black

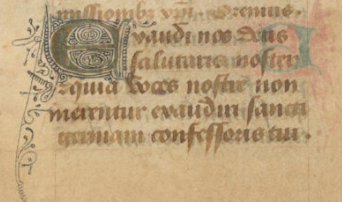

As for black, we were tasked with examining both the black penwork, which we see coming off both the initial and the text ink. For the ink, we hypothesized that it was iron gall ink and the initial penwork to be carbon black. Below is an image to show the pigments we were dealing with.

When going about analyzing our black ink pigments, we started by picking sections in the manuscript where we believed we would get the clearest readings on the pigments, places where interferences from other pigments, like reds or blues for example, were less likely to be picked up by the pXRF. For this, we ended up picking samples from 18v, 76v, 78v, and 60r to be analyzed.

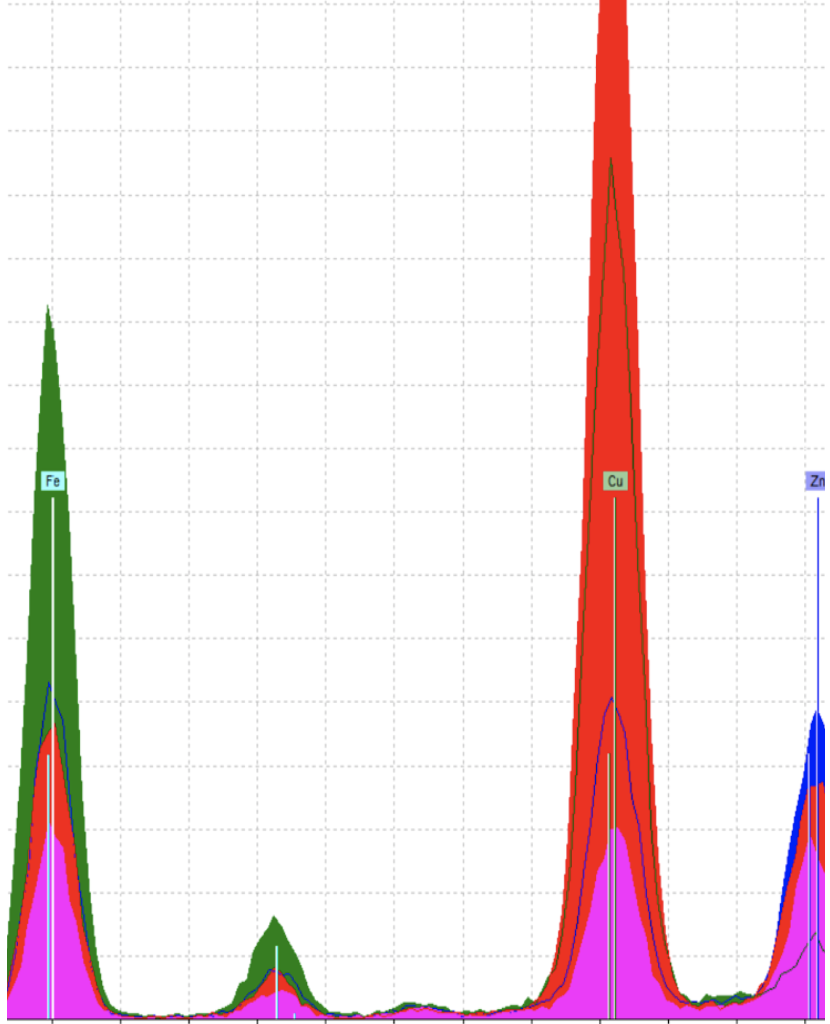

In this spectra, we can see how the four samples we took line-up with one another. Each sample contains iron and copper, with a little bit of zinc, all of which are common elements present in iron gall ink. At first glance, we were slightly worried about how our amounts of each element varied between the different samples, assuming that we were dealing with iron gall. To account for these inconsistencies, we had to go back into the Hargrett Hours and see whether interference from other pigments around our chosen spots could have been picked up, too. With 18v, the red line in our spectra, a blue (azurite) line fill is on the back of the sheet, which might have been picked up by the pXRF, which would explain that spike in copper. As for 60r, the green line, a different scribe was responsible for this page, which explains the different amounts of iron and copper, with the scribe working from a different ink recipe.

Despite the differences in amounts and recipe, the use of iron gall is consistent from beginning to end when it comes to the text.

Moving onto the black penwork, we were not as lucky in coming to a clear-cut conclusion. When choosing our samples to test, all the penwork came off of a gold initial, making it impossible to pick up solely the penwork. In addition to this problem, our text, which we discovered to be iron gall, was on the reverse side of every penwork sample. Because of this, when analyzing our spectra of the penwork, we see a similar spectra to that of our iron gall, only this time with the added gold from the initial.

We didn’t want to conclude that the penwork was iron gall because carbon black was also an option we were considering; however, because carbon black is an organic pigment, it cannot be picked up by the pXRF.

With this said, our spectra analyses were unable to definitively tell us what pigment makes up the penwork, whether it be iron gall or an organic pigment.

Red

We predicted that there are two different red pigments and that they would both be consistent across the manuscript. The first one is the rubric, which is very dark in appearance. The other is in the red penwork, which is a much more vibrant red. We predicted that the rubric is likely some kind of organic red, and the penwork is likely Vermilion. The first red pigment is the red penwork found in the initials and the second is in the rubric.

This is the spectra from the Vermilion red penwork spot we tested on 14v. You can see that there is a high amount of Hg, which is mercury. Cinnabar, and vermilion are red pigments which contain mercury sulphide. Vermilion and Cinnabar are indistinguishable from one another, and they were both commonly used around the time of the Hargrett Hours. With this spectra image showing a large spike of mercury, it is highly likely this pigment could be vermillion or cinnabar.

Next we have our spectra for the red rubric on 22r:

We tested three different spots, and the spectra looks relatively the same for all of them. You can see a large amount of calcium,with smaller amounts of other elements. The calcium can be found across the manuscript and is probably from the lime used to treat the parchment. The small spikes of iron, copper, and zinc are consistent with the pXRF’s plate and could have also been picked up from the iron gall ink text nearby. We are left with no elements that we can use to identify this red pigment. This leads us to the belief that this is an organic red pigment.

Organic red pigments come from plants, insects, and mollusks. There are many different organic reds that could have been used, and at this point it is not possible for us to identify any particular one as they do not show up in the spectra. As the three tested rubrics look the same, it’s likely that the same pigment is being used throughout; however, we have no evidence to back up this claim.

Conclusions

After sciencing our way through these spectra, it seems that the pigments in the Hargrett Hours are consistent with other 15th century Books of Hours, helping to validate our dating of the manuscript; however, our question of if every pigment of red, blue, and black we see throughout the book is consistent with one another remains unknown for some areas, like the black penwork and red line fills, as we explained above. This unknown arises from the use of organic pigments. We weren’t able to prove whether they were present or not by only using a pXRF. Although we weren’t able to identify the pigments in everything we tested, we were able to discover more than we knew before, like the use of azurite, iron gall, vermillion, and more. This whole process, from the initial research to writing this blog post, has opened our eyes to the complexities of making a manuscript, especially concerning the pigments.

References

“Carbon Black.” ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the Making, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/lab/overview-of-artists-materials/carbon-black/type/material.

“Azurite.” ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the Making, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/lab/overview-of-artists-materials/azurite/type/material.

Marieflemay. “Iron Gall Ink.” Traveling Scriptorium, Yale University Library, 8 Apr. 2015, https://travelingscriptorium.library.yale.edu/2013/03/21/iron-gall-ink/.

“Cinnabar and Vermilion.” ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the Making, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/lab/overview-of-artists-materials/carbon-black/type/material.

“Organic red colourants.” ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the Making, The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/lab/overview-of-artists-materials/organic-red-colourants/type/material.