The third and final part of Literature in the Library has been spent studying the ingredients, formulas, and processes that went into creating the pigments used to illuminate medieval manuscripts. The fragment that we analyzed was from the Hargrett Library MS 1286, which is believed to have come from 14th century France. It’s a 318 x 229 mm fragment from the Bible, containing what were then the books of Kings, but in modern versions of the Bible they’re the books of Samuel. The book of 1 Samuel ends on the verso side and 2 Samuel begins there with a colorful illuminated initial (Figure 1) depicting David and another figure.

This illuminated initial is where we did the pXRF analysis (the pXRF technology is explained in this post), and we analyzed five spots on the fragment, containing pink and green pigments, two different shades of blue pigment, and some gold leaf. Our goal in doing this study was to determine which elements are present in the pigments used to decorate this particular fragment, as a way to further our understanding of the recipes used to produce medieval pigments. It will also provide information that could be used to help identify the types of pigments used on other manuscript pages.

The Hypothesis:

We did preliminary research to get an idea of which substances and minerals were most commonly used to create medieval pigments, and based our hypotheses on that. For the pink, the most commonly used pigments were of organic materials, namely brazilwood and madder lakes. Brazilwood was our first guess, as it was favored due to its affordability and ease of use, and it results in a rose-pink shade when made into a pigment,1 which seemed similar to the shade of pink on this fragment. The problem with both of those pigments, however, is that they’re made of organic materials and therefore wouldn’t be easily detectable on an XRF spectrum. With that in mind, we didn’t expect to see much of interest in the pink spectrum, but we asked for a reading to be done of that spot anyway.

Interpreting the Spectra:

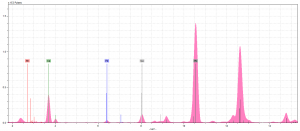

So now that we had analyzed our fragment (with Dr. Hunt’s help, of course), it was time to interpret the spectra (Figure 2), and see exactly what elements we could find. Our hypothesis was that our pink was either brazilwood, an organic pigment which does not contain any elements the pXRF is capable of reading, or a mixture of red and white lead, which would’ve resulted in very high lead peaks, and not much else.

Our spectra contained rhodium (Rh), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb). The Rh we can automatically ignore because it is from the pXRF machine, not the fragment. We expected some Ca, as the parchment contains some from the lime wash, but more on that later. The Fe and Cu are from the iron gall ink surrounding our initial (we saw these Cu and Fe levels consistently throughout all the spectrum).

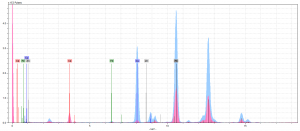

As you might be able to tell, neither of our initial theories proved true. At first, we thought there might’ve been something to the lead-mixture idea. Once we’d compared the peaks of Pb in our pink spectra to those in our light blue spectra (Figure 3), which we have determined contains white lead, it was clear that this was not the case. The pink Pb peaks aren’t any taller than those we saw across all our spectrum. Therefore, we chalked these peaks up as the result of underdrawings done in lead.

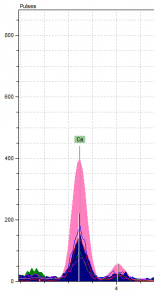

So now, ignoring the Pb peaks, we are left with a very quiet spectrum. This is when we took a second look at our Ca. If you look at Figure 4, which shows the Ca levels in all our spectrum compared, you’ll notice that the Ca in the pink pigment is substantially larger than rest. In fact, it’s the largest of all the peaks.

This was really interesting because we’d never encountered any calcium-based red or pink pigment in our research before our analysis. We explained away every other element on our spectra and were left with… calcium? According to our classmates’ color reports, as well as this essay2 about another manuscript analysis, Ca only shows up as a component of the parchment, as a prep layer for gilding, in organic lake pigments with calcite substrates or when gypsum, chalk, or bone white (a common umbrella term for calcium-based white pigments) are present.

We were left with a lot of ideas to bounce through. Through research, we found it was really common to mix either white lead or lime white (another umbrella term for calcium-based white pigments) with other colors for a variety of purposes3. That said, our final conclusion is that our pink pigment is the result of mixing an organic red or pink pigment with a calcium-based white pigment. Figuring out exactly which organic pigment created our pink color would require analysis with different technology capable of reading elements with lower atomic numbers, as well as microscopic examination.

There is also an element of risk to further attempts to determine the source of the red or pink pigment, as a method that works for one pigment may damage another. Madder lakes can be detected through the use of ultraviolet radiation and fluorescent reactions,4 but brazilwood is not very lightfast (it fades easily) and would be damaged by exposure to that type of radiation.5

by Heather Starr and Taylor Lee

1Thompson, Daniel V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. Print.

2Trentelman, K., et al. “Chapter 5: XRF analysis of manuscript illuminations.” Handheld XRF for Art and Archaeology , Leuven University Press, 2012, pp. 159–189.

3Sabin, Alvah Horton. White Lead: It’s Use in Paint. Brooklyn: Brownworth & Co., 1920. Print. https://books.google.com/books?id=HWxZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

4Andreas Burmester, author. “Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Volume 3” Elisabeth West Fitzhugh, editor. Studies in Conservation, no. 1, 2000. Print.

5Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. London: Archetype, 2003. Print.