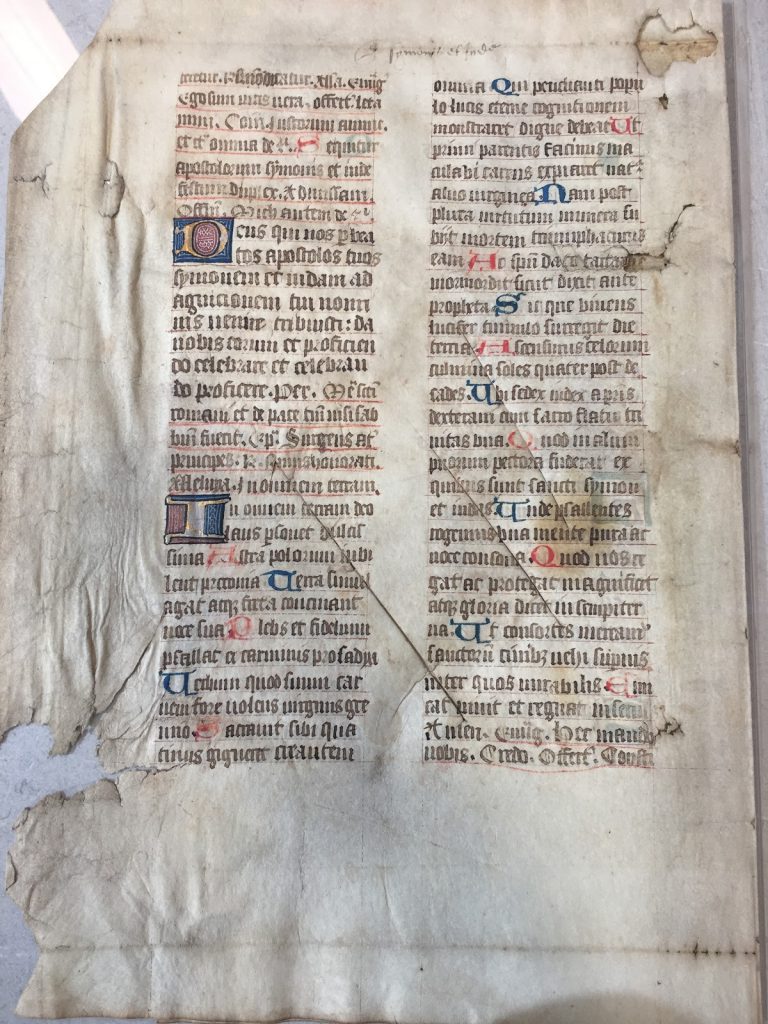

For the third unit of our class, Literature in the Library, we have been testing and analyzing pigment spots in medieval manuscripts. Using a portable XRF machine, we determined what elements were used in the pigments, and therefore which specific pigments were used on our fragment. Our particular manuscript is from the early 15th century and contains part of the Mass of the Catechumens. However, there is still a significant amount of information that remains unknown about our manuscript. For example, we do not know the country of origin or what caused some of the extensive damage our manuscript has sustained. The manuscript has several slashes and holes in it, as well as what appears to be a good bit of water damage. Because the manuscript is severely damaged and degraded we were not sure what to expect from the XRF spectrometry. We were afraid that the samples would be too degraded to yield conclusive results. Many of the spots we tested, namely the gold and black pigments, had faded over time.

Fortunately for us, the portable XRF machine had no issues reading the spots in our fragment. The spectra of our pigments were all fairly clean and “easy” to interpret. We most certainly had elements pop up in different readings that we were not expecting to find, but upon further investigation they were easily explained. We tested five different spots on our manuscript: one blue, one black, one gold, and two red. We tested two red spots because one was a rubrication and one was part of a decorated initial, and we wanted to see if the illuminator used the same red pigment in both spots.

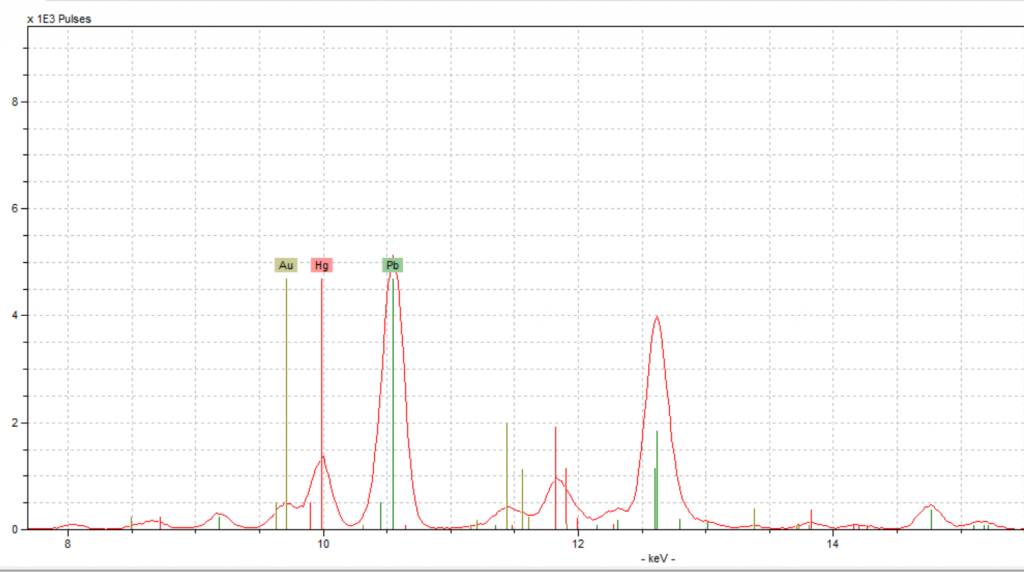

In medieval manuscripts, there were two main methods of making red pigments, vermilion and red lead. Vermilion (also referred to as Cinnabar) is composed of mercury sulfide (HgS), and it tends to have a deeper red hue (Douma, “Pigments Through the Ages”). Red lead, on the other hand, has more of a red orange hue and is composed mostly of lead (Pb3O4) (Howard, 125). We were interested to see if the two different reds we were testing, which were slightly different shades of red, were the same pigment. Both pigments contain heavy metals (Pb & Hg), which would be picked up by the pXRF machine. The other elements in each compound, oxygen and sulfur, are less likely to show up on the spectra.

Left to right: red lead, vermilion

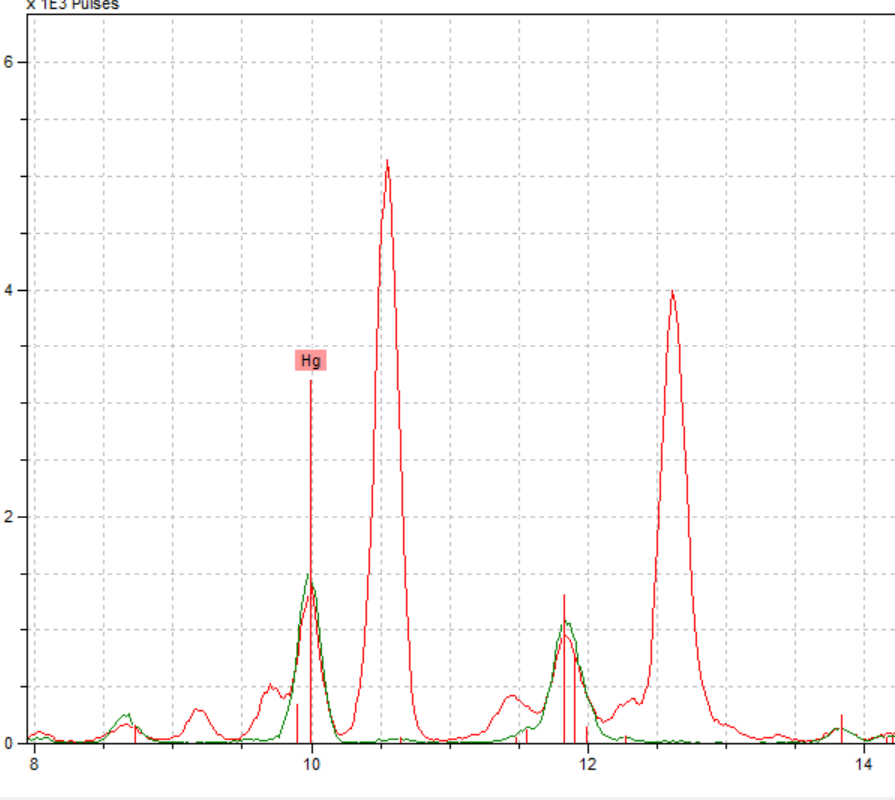

Initially, when we looked at the graphs of the two red spots, the results looked different. The spectrum of the rubrication gave us results that looked exactly like we were expecting, a strong peak of mercury with a few trace elements here and there. However, the red spot from the decorated initial yielded unexpected results. This spot had the peak of mercury we anticipated; however, there was also an unexpected tall peak of lead.

This peak was momentarily confusing because the lead peak seemed to indicate the use of red lead along with vermilion. To us, it didn’t make sense for there to be two types of red pigment in one spot. When we looked back at this spot on the fragment, we noticed that there was a white design on top of the red which is most likely lead white. Lead white was the most popular and common form of white pigment, and which has very high concentrations of lead (Pb) (Douma, “Pigments Through the Ages”). Therefore, the tall lead peak could be explained by the lead white pigment, leading us to conclude that vermilion was used for red, and there was no red lead present. Since vermilion was used in the decorated initial, that means the same pigment was used in the initials as in the rubrication. Furthermore, when we looked at the spectra for these two spots, the mercury peaks lined up almost perfectly, backing up our conclusion.

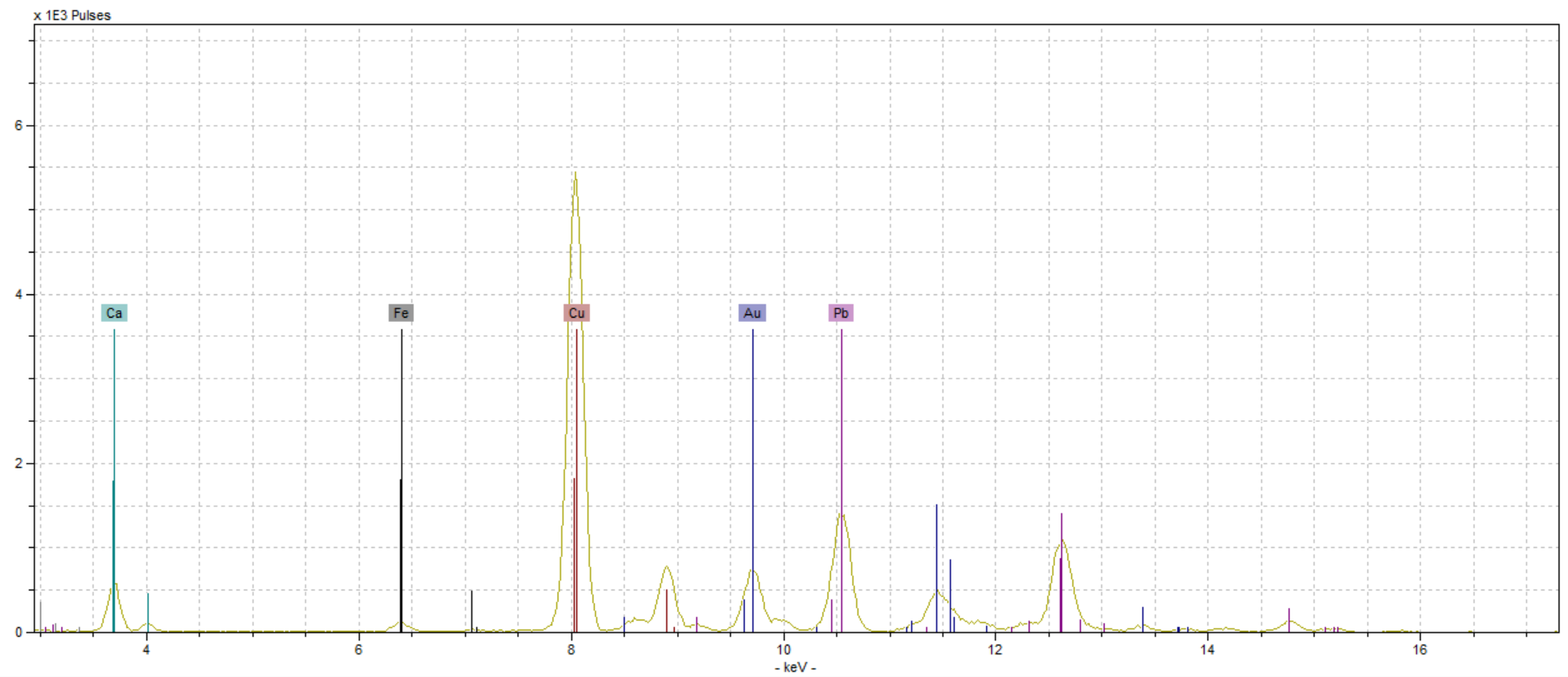

We also ran into a hiccup with our gold spot, but we anticipated that might happen. The gold spot we selected to test was very degraded, as seen in the picture to the right, and we were not confident that we would even get a gold reading.

The spectrum showed significant amounts of gold, which was good, but it also showed a significant amount of copper. While we were excited by the gold reading, we were confused by copper’s presence. These results required us to do some research into different methods of making gold pigments, specifically gold alloys. We found two primary methods of making gold, shell gold and gold leaf. Shell gold is a combination of gold and mercury, and since we did not have any mercury in our reading, we eliminated that as a possibility. Gold leaf, however, is a combination of gold and another metal, most commonly copper (Jackson, et al). We believe that this along with the azurite blue that is right next to the gold explains the high peak of copper in this reading.

While we originally anticipated that we would struggle with our spectra readings more than other groups, it turned out that most of our readings were easier to interpret than we initially thought. All of our hypotheses were proven, and we only had a few confusing aspects to our spectra. And on top of that, the unexpected elements that did pop up in our readings made sense once we took a closer look at where the spot was in the manuscript and what colors surrounded it. We’ve struggled with this fragment throughout the semester, from the weird damage to the barely-there text, and we thought we would continue to struggle with it in this unit. Thankfully, our fragment took pity on us and gave us beautiful results! All we can say is it’s about time.

-Lauren Amidon & Katie Knickerbocker

Notes:

Douma, Michael, curator. Pigments through the Ages. 2008. Institute for Dynamic Educational Development. Web. 4 December 2017. http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments

Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. London: Archetype, 2003. Print.

Jackson, Deirdre Elizabeth, Stella Panayotova, Paola Ricciardi, eds. “Colour: theArt & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts”.Harvey Miller Publishers, 2016. Print