It’s Eclipse Day across the US, and here at UGA we caught 99% coverage (which was, I learned by sitting in Sanford Stadium with 20,000 other people, a far cry from totality). Because the eclipse was scheduled to be at its fullest shortly after our class ends, I gave everyone an out-of-class assignment on medieval astronomy and medieval manuscripts instead. Starting with some explanations of how medieval astronomers envisioned the geocentric universe to function, students went on to consider how the cosmos were depicted in manuscripts and, particularly, how astronomical calendars and diagrams affected the physical layout of some manuscripts. (Shout-out to the British Library Medieval Manuscript blog for laying the foundation for today’s assignment in three blog posts: one on a tenth-century diagram of the solar system, one on images of the cosmos in manuscripts, and one on almanacs.)

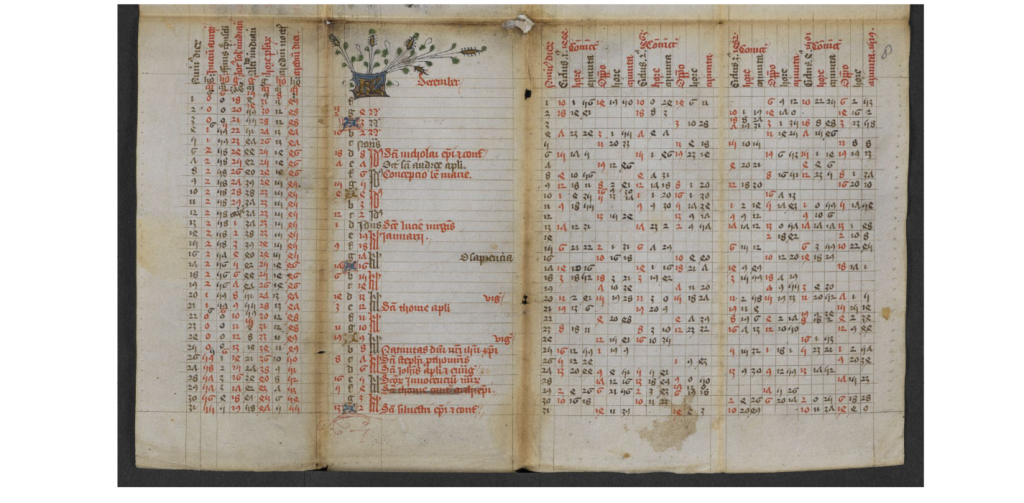

Of all the manuscripts the students were looking at, I was fascinated by British Library, MS Sloane 807, a c. 1455 folding almanac for use by a physician or perhaps a text for use in the field by an astronomer. These “pocket almanacs” are portable, bound in such a way that they could be attached to a belt and consulted on the fly. Its contents include an abbreviated form of the Kalendarium composed by the English astronomer John Somer c. 1380; Somer was Franciscan friar and almost exact contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer, and his astronomical knowledge was highly regarded. The Kalendarium is a handbook for how to anticipate major astronomical events: how to calculate the date of Easter (which falls on a different day every year), when sunrise and sunset will fall on different days, the length of day and night for each day, a table for locating the planets in the sky, and tables anticipating forthcoming solar and lunar eclipses. (Interestingly, many copies of the Kalendarium also include a table for how to read Arabic numerals; the shift from Roman to Arabic numbers is a pivot point for mathematical knowledge and advanced numeracy.)

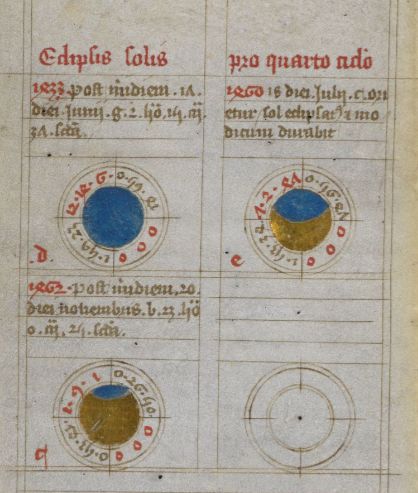

Sloane 807 is not a full copy of the Kalendarium; it only includes the basic tables, not the explanatory canons. But it does include a table describing the recently passed complete solar eclipse of 1433 and the upcoming partial eclipses in 1460 and 1462.

This table is a little weird to read, so let me try to explain. At the top of each diagram in red is the year of the eclipse – and yes, medieval Arabic numerals are formed differently than ours – followed by the date and the time of the eclipse, calculating from noon (instead of midnight) as 00:00. Around the diagram of the eclipse coverage is a ring divided into four quadrants; the set of three numbers in each quadrant gives (in hours/minutes/seconds), starting from the 9 o’clock position, the following calculations: the fraction of the sun to be eclipsed (with 12 being totality), the time from the beginning of the eclipse to its peak, the half-time of the eclipse duration,* and the total time of the eclipse (Mooney 46-47).

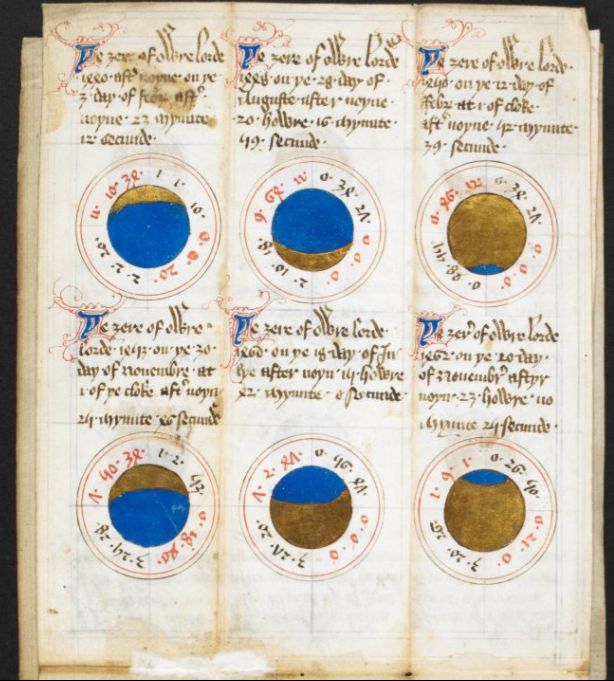

Here’s another table from a Middle English folding pocket almanac, BL Harley MS 937, c. 1430-31, giving eclipse tables for 1440, 1448, 1453, 1460, and 1462. Two overlap with the Sloane tables -can you identify which ones?

For more on medieval depictions of solar eclipses, the British Library’s manuscript blog has you covered.

The fact that astronomers like Somer could predict solar and lunar eclipses working from a mistaken model of the cosmos is an amazing feat. But what these manuscripts and almanacs also reveal is a deep interest in the movement of the stars, not only among astronomers like Somers but also people who we wouldn’t consider scientists today. Like Lady Joan Holland, mother of King Richard II, who was a patron of Somers’ original computistical treatise. Or like Geoffrey Chaucer, bureaucrat and poet, who translated a work on how to use an astrolabe, a time-telling and star-mapping device.

Why were medieval people so fascinated with the planets and stars? They believed in the interconnectedness of all creation. In the Ptolemaic universe, the outermost ring of the cosmos was the Primum Mobile — essentially, the engine of motion that drove all the motions of the planets and stars beneath it. And the planets, in turn, influenced the movements of people on the earth. Accordingly, medicine and astronomy were tightly linked (which explains why these almanacs were used by physicians). Chaucer plays with these ideas in “The Knight’s Tale,” in which the personified plants of Mars, Venus, Saturn, and the Moon shape the outcome of Palamon and Arcite’s competition for the resistant Emelye.

But my favorite medieval author who considers the interconnection of humanity and the cosmos is not Chaucer but his contemporary Londoner, John Gower. In the prologue to his Confessio Amantis, a collection of pseudo-exemplary tales told for the benefit of the lovelorn Amans, Gower inverts the usual medieval understanding that the planets influence humans. In the Prologue, Gower is deeply concerned with the political divisions that divided England, and he concludes that the degradation of political society was caused not by astronomical interference, but by the actions of rational agents: “Bot al this wo is cause of man, / The which that wit and reson can” (Prol. 905-06: But all this woe is caused by man, who has understanding and intelligence). Gower goes on to suggest that discord within humanity affects not only the political system, but also the physical motions of the whole world:

For as the man hath passioun

Of seknesse, in comparisoun

So soffren othre creatures.

Lo, ferst the hevenly figures,

The sonne and mone eclipsen bothe.

And ben with mannes senne wrothe;

The purest eir for senne alofte

Hath ben and is corrupt ful ofte,

Right now the hyhe wyndes blowe,

And anon after thei ben lowe,

Now clowdy and now clier it is.

So may it proeven wel be this,

A mannes senne is for to hate,

Which makth the welkne to debate. (Prol. 915-28)(For just as man has suffering

in sickness, so similarly

do other creatures suffer.

Lo, first of the heavenly figures,

The sun and moon both block them out,

And mankind’s sins make [them] angry;

The purest air on high

Has been, and is very often, infected because of sin,

Right now the high winds blow,

And immediately after they are quieted,

Now it is cloudy, and now it is clear.

So it may well be proven by this

That a man’s sin is to be hated

Which makes the heavens be in turmoil.)

By my reading, Gower has just given us an extreme form of the “Free Will” argument. Unlike the “Predestination” conception that cosmic forces govern human actions, and thus that humans are not fully responsible for their actions, Gower advocates for an inverse influence. The misuse of human freedom has caused, and continues to cause, ongoing disruptions in the heavens: not only bad weather, but the entire universe’s discord. “And whan this litel world [of the human body] mistourneth,” Gower concludes, “The grete world all overtorneth” (957-58). That is, when the microcosm of human actions are out of whack, so are the cosmic bodies that circle the earth.

I wonder what Gower would have made of today’s eclipse.

___________________________________________

*In most tables, this number is 0 0 0. I’m not good enough with medieval or modern astronomy to make sense of this, but the calculations for quadrants 2 and 4 do work out.

___________________________________________

Bibliography

Mooney, Linne R., ed. and trans. The Kalendarium of John Somer. Athens: UGA Press, 1998.