Feedback and its effects on students have been debated across many different disciplines, and linguistics is no different. There has been significant Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research into the effectiveness of error correction in second language learner writing. Some have taken hard stands on both sides of the debate such as John Truscott who argues against any sort of explicit correction in student writing. On the other side are researchers like Dana Ferris who argue that explicit error correction may not be bad for student learning. I agree with Ferris in that the research into error correction is too scattered to form any staunch conclusions (such as the ones made by Truscott that all feedback should be abandoned) (Ferris). Multiple studies seem to support both sides of the debate, and from personal experience in SLA, I can say that explicit correction at some levels seems to be an intuitive need in language instruction. In the specific metastudy The “Grammar Correction” Debate in L2 Writing: Where are we, and where do we go from here? (and what do we do in the meantime…?),” Dana Ferris thoroughly explores the available research into the debate and shows that the research is too inconclusive to make definitive claims. This inconclusively directly translates into the classroom as instructors are left with no clear path forward on the most effective way to help their students a second language.

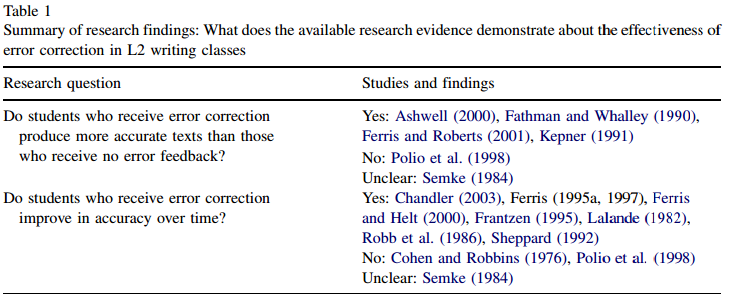

The indecisiveness of the collected SLA studies poses the biggest issue. Any broader claims made from this body have an undeniably precarious grounding. Ferris summarizes the current state of the research in the issue of error correction. Her primary tool for doing this are tables she constructs outlining the studies and what they report. She has tables (see figure 1 below) comparing very detailed and concise information about each study ranging from general research question to the specific demographics and methodologies of these studies. Each one makes a strong case in favor of what she is arguing. The tables clearly show that there is little to no consensus between the different studies. As we can see from figure 1, all the studies examined in that table report different

Figure 1. Small table she created summarizing the research findings of several SLA studies (Ferris 51).

Figure 1. Small table she created summarizing the research findings of several SLA studies (Ferris 51).

or contradicting results. There are some tendencies, but there is no clear answer. Also, they differ broadly from answering the general research questions such as the two in figure 1 to having vastly different demographics and methodologies. Each of the studies has different experiment durations ranging from a few tests to a whole semester. They all have different demographics ranging from American college foreign language students to English as a second language (ESL) students, and each study has a different implementations of error correction (some of the studies provide explicit correction, some provide implicit correction, and some give none at all). If these studies were trying to identify the effects of different types of feedback this would be acceptable, but often times this is not the goal of the study. If these studies want to make a claim as to the effects of error correction, then the method of correction should be established and consistent. These inconsistencies are an issue if one is trying to extract a conclusive answer from this data. Very few of the studies report the same finding, and they conducted the experiments in such a different manner that it is dubious that one could compare the findings directly. Any conclusions made are guaranteed to find a nearly equal amount of opposing data.

However, inconsistencies on the large scale are not the only ones to be found in these studies as differences can be teased out from the very detailed level. Most of the major studies she reviews do not even adequately define what an “error” is and how they classify them. Such as the studies in figure 1 which all studied different types of errors across different types of student writing. A lack of clearly defined variables causes major issues when trying to replicate such a study. Commonly, we may be able to identify what we think should be an error in writing (though “The Phenomenology of Error” by Joseph Williams demonstrates this isn’t even consistent); however, research should not slack to using loosely defined, colloquial senses of variables. In an experiment, every variable should be precisely defined and identified especially when that variable is the lynchpin of the study. Clear definitions allow for better scrutiny of the study. Without such information, the research is too imprecise to adequately replicate. Other researchers would be unable to know how to implement the test as the original did because the variables are not defined. These inconsistencies, not only on the broader level of research topics and overall conclusions but in the specific methods and underlying principles of these studies, show that the current state of the research is simply too varied.

Ferris does mention some possible trends that can be gleaned from the very few studies that show long-term, well defined, error analysis. These trends point in the direction that error correction is beneficial to SLA student writing (which happens to coincide with her personal findings), but she holds that a few studies are not enough to draw any major conclusions. They serve only to identify predictions based on the trends they seem to show. This distinction she makes is as crucial as it is true. From the tables she presents it is clear that many studies show leanings toward error corrections, but is not an overwhelming majority. This leaning is also not consistent (as discussed above). Hard stances and conclusions cannot be reputably made when the data is so small. Such conclusions would simply represent too small a sample size to make claims on student learning as a whole. The predictions that can be seen are important as they can serve to guide interest and practice into new research. But, they should not mistakenly be taken as sufficient evidence or proof.

All of these issues with the research body have really only one solution: more quality research. If the current state is to ever evolve beyond what it is now there must be more research that takes a different approach the majority of the current studies. Ferris discusses how the field needs actual, controlled, long term studies. She says that “it is imperative for the advancement of our knowledge about this issue that the absence of comparative longitudinal studies on the helpfulness of error correction in L2 student writing be somehow addressed.” (56) This is important because it helps minimize the randomness of any human endeavor. Writing is something that is affected by a myriad of variables such as personal and or cultural background, educational history, mood, etc., and so it is necessary to extend the studies to ensure the results are from the experiment (not just the students’ good days). However, duration of the study is not the only issue to correct. What errors are and how they are responded to have huge implications in these studies. Ferris states that “studies that define operationally which errors are being examined (and what is meant by ‘‘error’’ to begin with)” are needed, and she states that “we also need finely tuned studies on specific issues surrounding the treatment of error.” (57) If researchers want data that can be properly analyzed and replicated, then they must take these issues into consideration when planning their study. For studies of these issues to stand, the data must be gathered on precisely defined variables, methods, and procedures. If it is not, then the rest of the academic community can never validate the work.

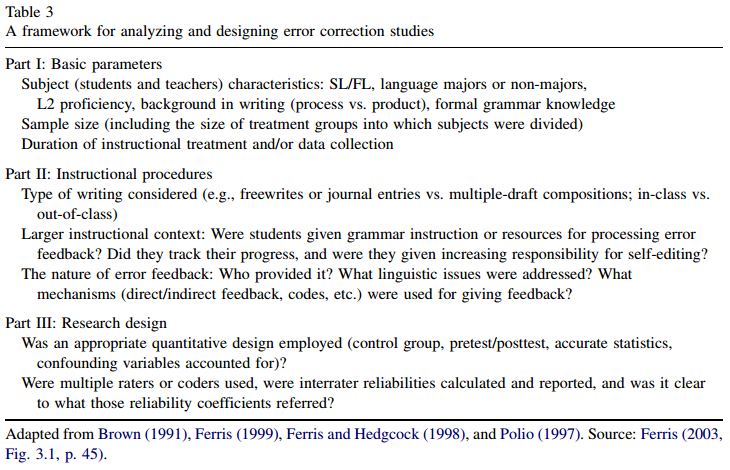

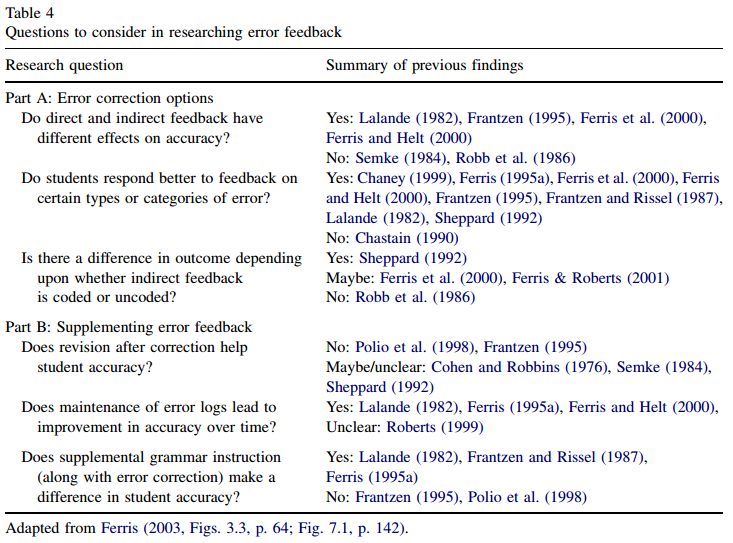

The final major issue is the ethical dilemma associated with a study on error correction. For a study like this students in some sort of educational institution are the best subjects. They are easy to access, organized, and probably in the institution for a longer time. They are exactly who researchers would look to for these studies (and college students often are the major demographic for all the previous studies) So, the ethical problem is if a researcher withholds a treatment that is potentially (and especially if it is expected) to be beneficial to the students then the researcher is intentionally stunting the development of those students. Many educational institutions do not like it when researchers interfere with student learning. Therefore, Ferris outlines some possible alternative study constructions that could circumvent the ethical issues. One proposal she makes that I think would be especially effective is to perform the study entirely on volunteers. If this study is presented to students as extra-curricular, with no penalty to work performance, then it seems that the ethical issue is resolved. Every party is informed, and the test body knows that it is an experiment that will deliver different treatments to different individuals. However, Ferris does not leave the proposal with simply that suggestion. She has two tables (figures 2 and 3 below). The first outlines a very detailed possible experiment, and the second outlines many questions that must still be considered in the research topic. This leaves researchers with a very effective call to action when considering her proposal. All of these suggestions are very valuable because they ensure that futures studies have some guidance on how to create stronger studies.

Figure 2: Her presentation of an improve error correction study .(57)

Figure 2: Her presentation of an improve error correction study .(57)

Figure 3: Her summary of important research questions with previous works. (58)

Figure 3: Her summary of important research questions with previous works. (58)

Lastly, she concludes with “what to do in the meantime (58).” She says that while researchers are working on these issues there are still students that must be taught. There are still teachers who are wrangling with these issues. Her suggestion is that until more research can be done, teachers must do the best with their intuitions and the expressed desires of their individual students. Teachers should try to implement the many possible methods for error correction the field has supposed in the best way that they see fit. Until anything conclusive emerges, the best anyone can do is work with what seems to be the most effective plan. This is unfortunately how teacher are going to have to proceed. Until a teacher can see a strong body of evidence that shows them what methods are the most effective, the negotiated desires of the students is the best said teacher has to use.

Overall, it is clear that the current state of SLA research into student error correction in writing is unsatisfactory. More research needs to be done so that an answer can be given with some degree of concord. Currently, Ferris’ discussion on the issues and possible solutions to these problems is very well structured, informed, and argued. Her vast synthesis of all the relevant research gives her study something many metastudies lack. It allows readers to be informed without being researchers of the field, and it proves she has done enough research to be qualified to make the claims she is making. Her conclusions hold through analysis of the data she presented. The body of research is inconclusive in results as well as methodology and procedures. If researchers in SLA writing want to be able to give solid conclusions on the effects of error correction, more better defined and consistent research must be done.

References

Ferris, Dana R. “The ‘‘Grammar Correction’’ Debate in L2 Writing: Where Are We, and Where Do We Go from Here? (and What Do We Do in the Meantime …?).” Journal of Second Language Writing 13 (2004): 49-62. Science Direct. Web. 6 Apr. 2016.