“Welcome to the Renaissance

Where our printing press has the fancy fonts,

That’s right we’re fancy, and very literary, theatrical too…”

“Welcome to the Renaissance,” Something Rotten! A Very New Musical

Shakespeare may be a name that you wouldn’t expect to hear around these parts. “But, this is a blog about medieval literature,” you may be protesting! Yes, yes, that is true – but as an Early Modernist, Shakespeare seems to permeate just about everything I do. Of course, this blog is no exception. Further, there is a great deal of overlap between the medieval and the early modern. Despite the convention of pitting the medieval versus the early modern (the hit musical Something Rotten! begins by listing the plague, the War of the Roses, the Holy Crusades, and the feudal system as being “so Middle Ages…[and] so Charlemagne”), in practice, much of the means of assessing medieval texts can be carried over to the early modern. Fundamental textual issues from our course included text circulation, medieval literacy, and mouvance. Not much of this changes between 1400 and 1600!

That being said, one major change does happen: the printing press is introduced to England in 1476 by Caxton, and thus changes the landscape of book creation. Plus, I’m preparing you for that inevitable Final Jeopardy question about 1476. The printing press revolutionized how books are created in England; books in England could now be printed, and text became a bit more settled. However, book text would still remain fluid for the next few centuries.

Of course, one of the major questions that first-time students have about Shakespeare is a (usually snarky) insinuation that Shakespeare “stole” all of his plots. You can see this addressed by the British kids show Horrible Histories in their video “Shakespeare goes to School” where Shakespeare’s claims that he “borrowed” his plots. Shakespeare’s plots come from Ovid and Greek myth, but more relevant to our discussion, Shakespeare takes from Saxo for Hamlet, Geoffrey of Monmouth for Lear, Chaucer and Caxton for Troilus and Cressida, Chaucer alone for Two Noble Kinsmen, and Holinshed’s Chronicles for the Henriad (Cooper).

As the unnamed gentleman in Hamlet says about responses to Ophelia’s words, that they “botch the words up to fit their own thoughts,” so does Shakespeare in his own rendition of medieval sources (4.5.11). This quote is typically used to describe adaptation of Shakespeare, but here it can readily explain the textual instability inherent in studying Shakespeare. Not only do adaptors of Shakespeare “botch” his words, so does Shakespeare “botch up” the words of medieval writers before him.

This reworking is a symptom of mouvance, credited to Paul Zumthor. You can read more about mouvance in my previous blog post, accessible here. Mouvance is the idea that “medieval vernacular works were not normally regarded as the intellectual property of a single, named author, and might be indefinitely reworked by others, passing through a series of different états du texte (‘textual states)” (Millett). While mouvance relates more to the question of editing medieval texts, it can also describe how and why Shakespeare’s plays rewrite previous plays. In short, Shakespeare borrowed just as other authors borrowed; this pattern can be traced through Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida: inspired by Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde who sourced his story from Boccaccio’s Il Filostrato, who sourced his text from Sainte-Maure’s Roman de Troie (“Dates and Sources”). Mouvance at its finest.

Let’s look, then, at a specific example of this textual instability in practice. Alongside this class, I have been annotating Shakespeare’s Henry V in conjunction with its historical sources. In reading Henry V it becomes clear that textual instability and mouvance are of utmost importance to the play. For all of you non-Shakespeare fans out there, Henry V is the final play in the “Henriad,” or the collection of four history plays (Richard II, Henry IV Pt. 1, Henry IV Pt. 2, and Henry V) detailing the ascent of Henry V and the Plantagenet line, that would lead into his previously written but chronologically later history cycle comprising Henry VI, Pts. 1, 2, and 3, and Richard III. These two sets of plays make up the majority of Shakespeare’s History plays, and with the category of “History,” it’s pretty clear that these plays need to address, y’know, history. Clearly, Shakespeare was not alive for the events of these history plays. Richard II began his rule in 1377 and Richard III died in 1485, making the events of the play almost a century older than Shakespeare himself (born 1564).

How, then, would he go about writing plays about these characters? History! This meant turning to Holinshed’s Chronicles and Hall’s Chronicles. The chronicle format flourished in the Early Modern era, especially because of – you guessed it! – Caxton and the printing press because of the relative ease of printing. Chronicles existed prior to the Battle of Hastings: see the Anglo Saxon Chronicle or Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) or Wyntoun’s Orygynale Cronykil. As a genre, chronicles were narrative devices; they provided the history of a kingdom compiled in one place and written in an elevated style, marking an attempt to add formality and structure to English history.

Hall’s Chronicle came first; it was written in 1548 and revised and enlarged in 1550. In his Chronicle, Hall included historical events from 1399 to 1509. This covers the death of John of Gaunt and Bolingbroke’s return to England from exile while Richard II was in Ireland in 1399 to Henry VIII’s ascension to the throne in 1509. You may note that this suspiciously follows most of Shakespeare’s plays from Richard II to Richard III.

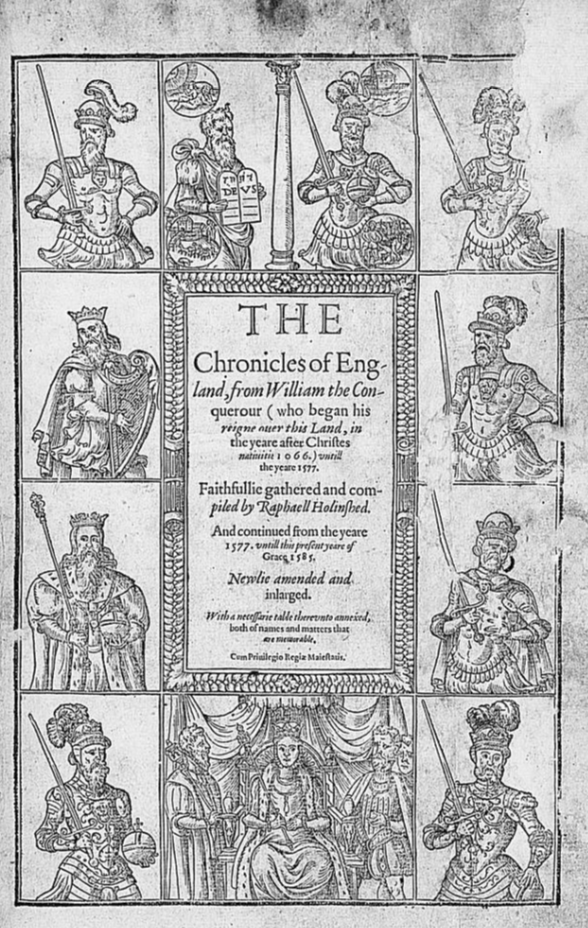

This becomes the basis for Holinshed’s works of 1577, and the revised 1587, which is the one that I have been consulting for my own research into the sources of Henry V. This text encompasses 1066 and the Battle of Hastings to 1587 and the death of Mary Queen of Scots (Holinshed Project). Hall took the approach of discerning causation of events rather than simply retelling the events. Despite being the “source” for Shakespeare’s texts, even Holinshed suffers from anachronism and narrativization. Harriet Archer notes in her essay for The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles that Holinshed seems to ignore the Middle Ages:

For Holinshed, there was no such thing as the Middle Ages. In the Chronicles, we witness the years between 500 to 1500, from the classical past to the early modern present, by turns flattened by anachronism and divvied up by dynasty. Nowhere, though, are they made to form a single and distinct historical period.

(Archer, Harriet 171)

Even the sources suffer from textual instability, as Holinshed and Hall permeate their text with anachronism and editorializing. Hall and Holinshed further influenced one another. Holinshed’s Chronicle follows much of the same history as Hall, and uses Hall’s distinctive style. Is it any real wonder, then, that Shakespeare’s Henry V deviates from historical record in many ways?

All of this comes together when examining how Hall and Holinshed influenced Shakespeare’s texts as sources. In fact, even Hall and Holinshed borrow text from one another, as Holinshed borrows the colloquial style of Hall. The most obvious description of this can be found in the Salic Law description from the Archbishop of Canterbury in the first act of Henry V. The Salic Law scene can be found in 1.2.37-100 (yes, it’s long!); it is essentially a description of succession laws in fifteenth century England and France. For the too long, didn’t read version: The Archbishop says “French claim” = bad claim. This scene remains important, despite its flaws, because of how it demonstrates Shakespeare’s reliance on Holinshed. In the 1587 edition of the Chronicle, Holinshed includes a description of the “archbishop of Canturburie” making “a pithie oration” about “Salike law” (Holinshed). Much of the language of this speech in Henry V – structure, form, and content – is lifted from Holinshed almost directly.

Not only does the lifting of this speech speak to textual mouvance, but it highlights how strategic lifting of language in later texts by later authors can add legitimacy to a later work. In a theatre review of the Public Theatre performance of Henry V in 2003, critic Ron Rosenbaum calls the speech “complicated, arcane, esoteric, [and] a challenge to actors and directors,” all of which are true (Rosenbaum). He goes on to note, however, that Shakespeare singles this speech out as a means to frame the play.

I agree with Rosenbaum’s assessment of the speech, but perhaps for different reasons; while he goes on to describe how the speech can be used to frame the titular Henry as a Machiavel or a hero, I would point out that Shakespeare uses this direct lift from Holinshed to provide legitimacy to his own retelling of history. Rather than attempting to delineate the rules of succession on his own, Shakespeare follows the seeming idea of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Not only does Holinshed describe the rules of succession in an honestly less complicated manner than it easily could be, but it would also be familiar to audience members who had read Holinshed’s work.

You can see the surprising overlap between Shakespeare’s early modern period and the medieval period our class has been exploring all semester. Issues of textual instability and mouvance have shifted and changed, but are still prevalent. My research on Henry V and reading of Holinshed and Hall’s Chronicles from the 1500s has grown my appreciation for the physical book of the era. So, while “our printing press [may have] the fancy fonts,” skills learned in this class for working with medieval books can transfer to the Chronicles of the early modern.

Works Cited

Archer, Harriet. “Holinshed and the Middle Ages.” The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles, edited by Paulina Kewes, Ian W Archer, and Felicity Heals, Oxford UP, 1 March 2013, pp. 171-186.

Archer, Ian W. and Felicity Heal, Paulina Kewes, and Henry Summerson. The Holinshed Project. Southampton, 2013. http://www.cems.ox.ac.uk/holinshed/

Cooper, Helen. “Shakespeare’s Medieval World.” University of Cambridge Research, 1 May 2010. https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/shakespeares-medieval-world

“Dates and Sources.” The Royal Shakespeare Company, n.d. https://www.rsc.org.uk/troilus-and-cressida/about-the-play/dates-and-sources

Holinshed. Chronicles. Folger Shakespeare Library, Early English Books Online. Web. http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2003&res_id=xri:eebo&rft_id=xri:eebo:citation:259710137

Horrible Histories. “Shakespeare goes to school.” CBBC, 15 April 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDWV_b3mgPk

Millett, Bella. “What is Mouvance?” Wessex Parallel Web Text, 9 Sept. 2014, accessed 22 Oct. 2018. https://www.southampton.ac.uk/~wpwt/mouvance/mouvance.htm

Rosenbaum, Ron. “Theater; The Crucial First Clue to ‘Henry V.’ New York Times Archives, 29 June 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/29/theater/theater-the-crucial-first-clue-to-henry-v.html?ref=oembed.

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Folger Digital Texts, ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles, https://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/?chapter=5&play=H5&loc=p7.