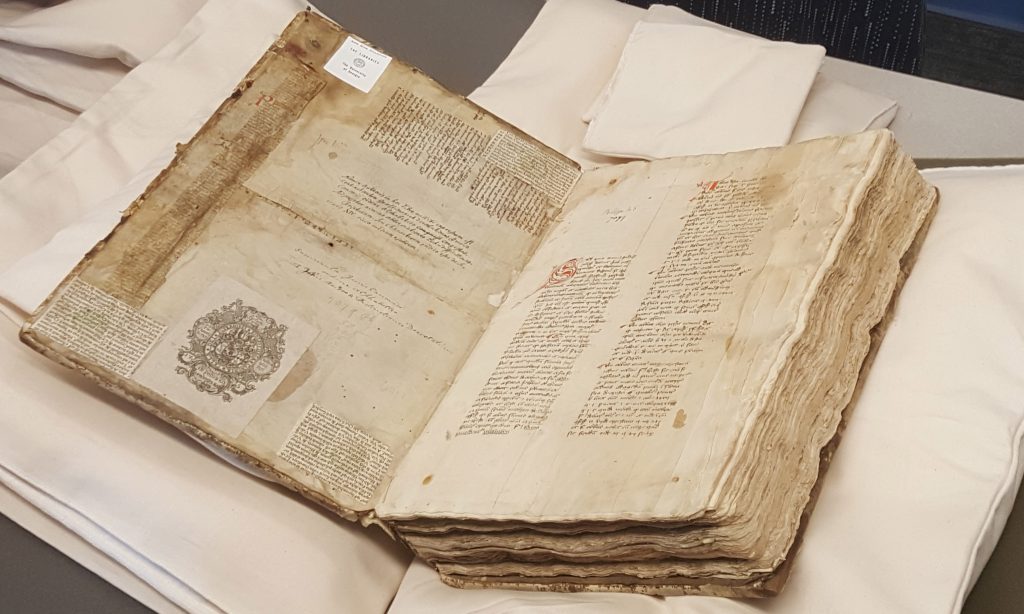

We wrapped up our service-learning project – helping the librarians reconceive a way to improve the discoverability of our medieval holdings while also improving the accuracy of information about them – last week. In some ways, the unit was an exercise in frustration for all of us; in others, however, the experience was a rip-roaring success.

As we talked with the librarians, especially Jason (our everyday librarian) and Anne (one of the rare books curators) about the current Hargrett Library website and the larger schema of the library’s organization, several things became clear that I hadn’t thought through clearly when first planning the project with Anne. First, although the website is out of date (and the librarians recognize that), they have little control over when it gets a facelift. There is a plan in place for the Special Collections website to migrate to the same platform as the current UGA Libraries main page is built upon, but there is no timeline for that migration. Some of the reasons for the delay can be chalked up to institutional inertia, but some are technical (the new platform needs to play nicely with the databases that serve the Special Collections catalogue). So although there will someday be an opportunity for the librarians to take our students’ suggestions into consideration, that day isn’t yet on the horizon.

Second is the “special pleading” problem. Why should the medieval materials get special treatment on the website when they constitute such a small portion of the library’s collection? The Hargrett Library collects in six different areas, and our medieval and early print materials fit into their History of the Book area. So it would make more sense, some students decided, to improve the publicity for all of the History of the Book materials. While the right way to approach the “special pleading” problem, this solution runs into a staffing issue. The librarians only work so many hours a week, and they haven’t got the time to completely repopulate a new library subsite for the History of the Book (let alone the other five collecting areas too).

The third issue was more ephemeral, but the one that some students found most challenging: the inherent problem of curating vast amounts of data, displaying that data in a user-friendly way, and managing that display for growth. As one student put it, there’s “just the sheer amount of information that has to be included, combined with finite financial and human resources” to manage it. Some of the students’ most savvy ideas for curating our medieval items’ records involved manipulating the library’s catalogue in impossible ways; it simply isn’t created for extracting the information the students wanted of it. Conversely, the simplest solution to gathering all the medieval materials into a single list – a static webpage – is also the most time intensive to update as the collection grows. In short, even if the conditions were right for implementing a webpage that showcased all our medieval materials, the backend infrastructure isn’t right for building a dynamic and easily searchable webpage.

So, in terms of actually implementing any of their designs, the frustrations were palpable. (Although, hey, this is life in a large organization. Frustrations R Us.) In terms of the students’ learning, however, the unit was an amazing success. I was blown away by their reflective comments, so I’ve culled a few soundbites (with permission, of course) to help demonstrate what the students got out of it.

Much of that success was in helping them learn what academic librarians actually do. Those who had volunteered in their public libraries in the past had some inkling, but everyone discovered just how diverse the job of an academic librarian can be. They do as much (or more) information management, education, and outreach as they do helping patrons use the materials. But working closely with the librarians for a couple of weeks also helped to break down the unspoken divide between student and academic grown-up. As one student put it about working with Anne and Jason to think through some of the website challenges, “I think, as students, we see librarians and teachers as these authority figures that think a lot more highly and sophisticated than us, but at the end of the day, they think just like us.”

Another element they took away was the opportunity to work through a real-world design problem. This is something that (if I can brag on my colleagues for a minute) the UGA English department does well. Dr. Elizabeth Davis‘s work with the Archway Partnership has given our students the chance to (for example) help redesign the Metter-Candler County Chamber of Commerce website; Dr. Davis’s class is currently part of the Highway 15 Coalition/Traditions Highway project. Our service project was less ambitious, but even here the students got some hands-on design work: “Here I am using the web design skills I am just starting to try to develop … and getting to have a real actual client for practice to boot. Serendipity, you might call it.” And developing these design ideas really pushed the students to think critically about the context of this project: “Let’s take a step back and think, why does it work there? Would it work on my platform? Which of these cool things is best suited for Hargrett, medieval materials, and all the specification and limitations that involves?”

And these students came up with some really smart designs for the librarians to consider when the migration does occur. Several of the librarians (including those who weren’t working with my students every day) and faculty members who saw their proposal presentations remarked upon the thoughtfulness of their web designs and great ideas they had. Every proposal had something in it that I anticipate seeing online here in a few years. As another student put it, “I think the librarians have an awesome and diverse pile of ideas and possibilities to choose from and grow a implementable design out of.” Truth.

Finally and perhaps most uniformly useful was the experience of preparing a formal report. We in English departments are great at teaching students how to write clear and provoking prose, and to develop sophisticated written arguments based on a nuanced understanding of evidence. These writing skills are transferable to any professional environment – but our students don’t often get the opportunity to practice that transfer in the classroom. Every student commented positively on this experience (even when it was painful). Here’s one pithy example: “Learning how to write a professional proposal was a great experience. … It’s definitely a useful skill to have, but I didn’t expect it to come from a class on medieval manuscripts!”

Which is exactly one of the remarkable elements of this series of classes. As physical objects as well as repositories of texts, manuscripts invite such a diverse array of intellectual approaches that they can support almost any pedagogical approach.