This semester’s class has been a little different from courses past. Instead of doing a deep dive into a single manuscript, the Fall 2021 students have studied the materiality of manuscripts and early printed books. This course has asked questions like, how were books made? How did elements of manuscript culture get remediated into early print culture, and what were early printers doing new? How do things like page layout, frontmatter, glosses, or indices inform a reader’s engagement with a book? We also asked questions that troubled the “normalness” of Western book culture. Questions like, what role does orality play in the transmission of texts? How did books circulate in the Islamic world, and why was the printing press not a revolutionary technology there? How did the Cherokee people appropriate white colonial concepts of writing systems to retain some cultural independence from the colonizers?

In short, what can we tell about a text’s purpose and movement through the world by looking at how it was made?

After spending all semester asking these questions of medieval and early modern books, students applied these concepts to a book of their choosing in their final projects. Many of them are writing about those projects here on the blog. Some worked with books closely related to the course content: medieval manuscripts of Chaucer or mystical texts, Caxton’s second edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. One picked up the class’s decolonializing theme and dove into an 18th c. manuscript of the Bhagavad Gita. Others chose more modern books: artists‘ books, comic books, diaries. Others still studied books their families owned: a much-used family bible, a grandmother’s collection of bibles, a small-press family genealogy. The breadth of their research – covering 600 years of book history on three continents — speaks to the long legacy of book materialites that originated in the Middle Ages. It also speaks to the thoughtfulness with which these students have engaged with the course’s big questions, their ability to see continuities between medieval and contemporary book cultures while honoring the critical differences between them.

One theme that recurs through these blog posts is readers’ desires to make their books their own. In each case, readers refuse the idea that a book is a commercial product meant only to disseminate information consumed by the eyes. This commercialism is visible in Caxton’s second edition of the Canterbury Tales, as two different students pointed out. For other blog writers, though, the book becomes a site of exchange between readers and writers over time. This desire to personalize is, of course, a natural feature of manuscript culture, where all books were handmade, often to the original owner’s specs. But this is not solely a medieval act; even a twentieth-century girl could make her own diary from scratch paper, taking control over the material form of her personal book just as her narrative made sense of her daily life. Both medieval readers and modern book-owners would write in their books, whether to mark passages important to the reader (if less so to the original writer), to record family births and deaths on every blank space of a family bible, or simply to dedicate a precious volume to a precious child. Books become objects of affect, a site for affirming social bonds. They also become objects of change over time, as generations of users deploy them in different ways.

For some book makers, refusing commercialism means pushing against industry norms: resisting censorship and sexism by creating wimmen’s comix; printing a book not for commercial gain but for preserving family history; crafting an artist’s book that evokes elements of sea and air through paper and ink; using a non-codex book form to engage readers’ hands, bodies, and imaginations in new ways. In the books explored in these blog posts, both readers and makers ask what a book might do beyond simply being a container for words, and how readers can engage – creatively, critically, and politically – with the possibilities of bookishness.

Michel de Certeau reminds us that “to read is to wander through an imposed system […], a system of verbal or iconic signs [that] is a reservoir of forms to which the reader must give a meaning” (169). These blog posts show how the materiality of the book too offers a “reservoir of forms” to which readers can also “give a meaning” as they manipulate, produce, or modify books to fulfil their desires.

References

Michel de Certeau, “Reading as Poaching.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. by Steven Rendall (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988), 165-76.

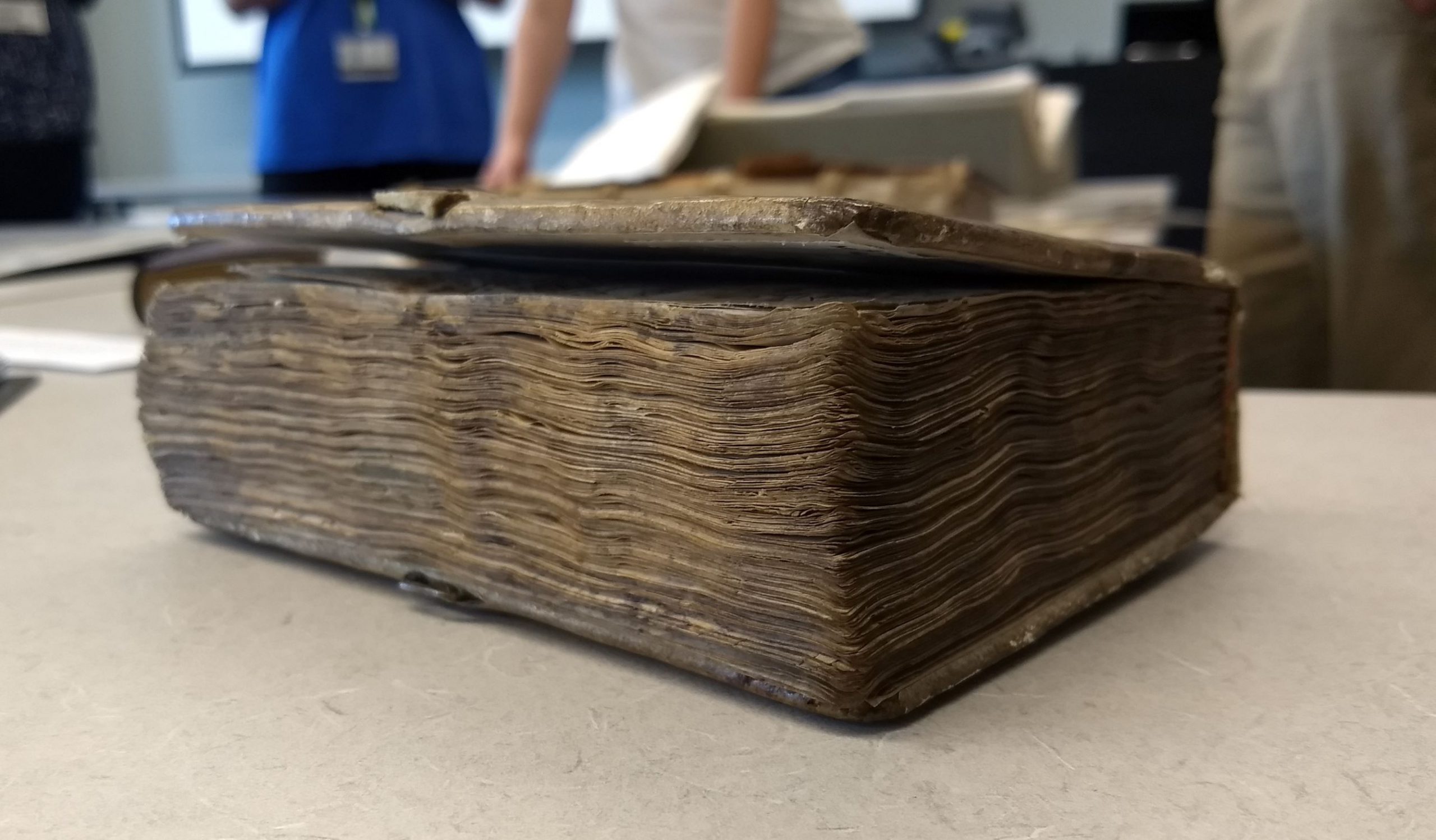

Header image: A manuscript in its original binding from the collection of Dr. Scott Gwara, University of South Carolina, in Fall 2017.