|

Author & Year |

Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Yilmaz et al., 2015 | Setting: Department of Social and Developmental Pediatrics, Ankara, Turkey

Description: Participating patients arriving to the hospital for well-visits were given questionnaires to be filled out by parents regarding the demographics of their family and child and the typical amount of time spent watching a TV screen. Participants were assigned to an intervention group or control group dependent on randomly assigned numbers and their baseline BMI was recorded. The intervention group was given four intervention components aimed at reducing screen time of the child. There were three CD recordings coupled with printed material that warned against the harmful effects of excessive screen time. The fourth component was a counselling over the phone. A component was delivered every 2 weeks beginning immediately after the baseline questionnaire. A follow-up questionnaire was given 2 weeks after the last intervention component. The control group also filled out the baseline questionnaire but did not receive any intervention components. |

n=363

C: n=176 I: n= 187

Children included were between the ages of 2 and 6 and current patients of Dr. Sami Ulus Children and Maternity Training Hospital in Ankara, Turkey |

Mean change in child media time (min/d)

Mean change in caregiver media time (min/d)

Reports of aggressive and delinquent behaviors (according to Child Behavior Checklist)

|

Child media time was significantly less than baseline in the intervention group after the 9 month follow-up. (t=50.1, P<0.001)

Caregiver media time was also significantly less than the baseline after the 9 month follow-up (t=13.41, P=0.001)

Parental report of aggressive behavior decreased significantly compared to the control group (t=2.79, P=0.006)

|

2 months

6 months

9 months |

| Andrade et al., 2015 | Setting: Urban schools of Cuenca, Ecuador

Description: Researchers performed a cluster-randomized trial on 20 schools. The students reported the length of time they typically spend watching TV during the week and on the weekends. The 10 schools in the intervention group engaged in a two-stage program to reduce sedentary behavior. During the first stage students received workbooks related to physical activity while parents were involved in workshops that stressed the importance of at least one hour of physical activity and limiting TV viewing to a maximum of 2 hours a day. Adolescents were also encouraged by well-known athletes to be physically active. The second stage involved teaching ways to overcome barriers to physical activity to adolescents and in an additional parent workshop. During this stage the schools also set up a walking trail on their floors. Both groups of schools were mandated by Ecuadorian government to receive physical education classes but the control schools did not take part in any intervention practices. |

n=1224 (20 schools)

C: n=608 (10 schools) I: n= 616 (10 schools)

Adolescents included were between the ages of 12 and 15 enrolled in the eighth or ninth grade.

|

Sedentary screen time on a weekday

Sedentary screen time on a weekend day

Total sedentary screen time on weekends and weekdays

Proportion of adolescents with screen time over an average of 2 hours |

The change in total sedentary screen time during the weekend and weekdays was significantly more in the intervention group than that of the control group (beta=-14.8 minutes, P=0.02)

Sedentary screen time during the weekend in the intervention group was significantly less than the control group (beta=-25min, P=0.03)

Sedentary screen time on the weekday increased in the intervention group while it decreased in the control group (beta=21.4 min, P=0.03)

The proportion of adolescents spending more than 2 hours a day on screen time increased significantly after 28 months for both the intervention and control groups. Control groups increased 26% from baseline and intervention groups increased 21%. (P=0.001) |

18 months

28 months |

| Maddison et al., September 2014 | Setting: Households in the greater Auckland metropolitan area of New Zealand

Description: Households were randomly assigned an experimental or control condition. Both groups had an initial physical assessment before intervention and measures of sedentary time, diet, and physical activity were self-reported. Caregivers in experimental households were given educational sessions that emphasized the importance of being a role model for their children in regards to reducing screen time. Methods of budgeting screen time, providing praise and encouragement, and positive reinforcement were also shared with caregivers to be used during the intervention. Parents were also provided with monthly newsletters via online website that provided strategies for implementing better behaviors in the home. Time Machine TV monitoring devices were used to track the use of TV and parents were give 30 tokens. Each token provided 30 minutes of TV time and parents could allocate them however they chose. Lastly, intervention households were also provided with an activity pack that included colored pencils, rope, cards, balls, and board games. The control group was instructed to go about their typical household behavior. |

n=251

C: n=124 I: n=127

Adolescents included were between the ages of 9 and 12, spent at least 15 hours a week engaged in sedentary screen time, considered overweight or obese, and spoke English |

Anthropometrics (BMI, height, weight, waist circumference)

Sedentary behavior

Physical activity

Dietary intake

Enjoyment of physical activity and sedentary behavior

|

The intervention group saw a 0.03 decrease in BMI from the baseline while the control group saw 0.05 decrease. The difference in BMI between both groups was not statistically significant (p=0.64, 95% CI: -0.08, 0.05)

Between the intervention and control groups there was also no significant difference in sedentary behavior or physical activity. From baseline measures, physical activity in the intervention group increased significantly (p=0.06, 95% CI: -0.94, 49.51)

Differences in enjoyment of physical activities and sedentary behavior were not statistically significant as well as dietary intake and length of sedentary time.

|

24 weeks |

Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

The Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends this strategy of reducing sedentary screen time in children 13 years and younger based on evidence including studies of interventions to limit screen time and promote physical activity were used. Upon the most recent update for this intervention strategy in 2014, the Task Force has stated some recommendations in order to resolve implementation issues, improve the effectiveness, and reduce potential harms and evidence gaps. The systematic review conducted by the Task Force involved 49 studies with 62 study arms. The Task Force recommended that this intervention be coupled with family-based social support given this aspect was the most common intervention component used in the included studies. In addition, the Task Force recommends including intervention materials into classroom curriculum by eliminating competing barriers to doing so. After review of the literature referenced in Table 1, I found that there is evidence both supporting and conflicting with recommendations for the intervention and its efficiency in reducing sedentary screen time and increasing physical activity.

This current recommendation is not a change from the previous systematic review done in 2008 that resulted in there being sufficient evidence to determine the strategy efficient. The Task Force based their recommendation on the observed outcomes from seven qualified studies which found that reduction in screen time was effective in improved measures regarding weight. The two reviews recommending the strategy are a change from the 2000 review in which the Task Force suggested that there was insufficient evidence to determine the strategy’s efficiency. At the time, the strategy was more specific to increasing physical activity and reducing screen time by the use of classroom-based health education. The Task Force found that the results of these interventions were inconsistent with only three studies qualified for review. With significantly more qualifying studies included in the last two reviews and more consistent results among them, the recommendation for this intervention has changed as the evidence supporting it became stronger. As shown in Table 1, Yilmaz et al. found that interventions such as this significantly reduced sedentary screen time in both the child and the caregiver, emphasizing the importance of the Task force recommendation in regards to coupling intervention with family and social support (2015). The study done by Andrade et al., however, resulted in an increase in the proportion of adolescents spending more time engaged in TV, computer use, or video games than what is recommended (2015). This trend occurred in both the control and the intervention groups of the study during their 28 month follow up. Andrade et al. suggest that this characteristic in the intervention group may be a result of the delivery of the intervention in which the second stage lacked components that focused specifically on reducing screen time in the same manner as the first stage (2015). Finally, the study done by Maddison et al. provided little evidence supporting the recommendation of the Task Force. Results regarding differences in dietary intake, BMI, physical activity, and sedentary screen time behavior between the control and intervention groups were not statistically significant (2014). There was, however, a significant increase in physical activity in the intervention group from the initial baseline measure (Maddison et al., 2014).

Based on the evidence provided from the Task Force and the previously mentioned studies, I would recommend this intervention as an efficient strategy in reducing screen time and suggest that it be facilitated in the household in order to promote family and social support and yield more significant results.

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

Theoretical Framework

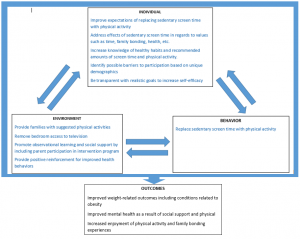

I’ve chosen to utilize the Social Cognitive Theory in planning an intervention program to decrease sedentary screen time and increase physical activity among children. The Social Cognitive Theory considers various elements pertaining to the individual, their environment, and behavior in how all of these elements influence one another to ultimately derive the behaviors we observe every day (NCI, 2005). The theory suggests that the likelihood for one to alter a health behavior lies heavily in their level of self-efficacy, goals, and their expected outcome (NCI, 2005). The triad of behavior, environment, and the individual emphasizes that each component of the theory is capable of leveraging changes in the others (NCI, 2005).

Theoretical Constructs:

Individual:

Behavioral capability: This construct is defined as one’s ability to perform a particular behavior based on their knowledge and skill (NCI, 2005). In the context of this intervention, it would be beneficial for participants to have knowledge regarding the negative effects of excess sedentary screen time and the importance of physical activity. Participants are more equipped to continue habits learned during the intervention once they have become more knowledgeable of the potential benefits. For children involved in this intervention, knowledge needs to be shared in way that is tailored to their learning capabilities as they will during counseling sessions in which they will learn the recommended amounts of physical activity and screen time.

Self-efficacy: This construct refers to the confidence of individuals in their efforts to change and make better behavioral decisions (NCI, 2005). In order to increase self-efficacy before and during an intervention, goals need to be realistic and specific (NCI, 2005). In the contexts of this topic, participants would need engaging alternatives in order to reduce screen time. This intervention will encourage the use of physical activity to do so and hopefully produce a habitual behavior change in the participants.

Expectations: This construct refers to the outcomes that the individual foresees as a result of their change in behavior (NCI, 2005). Expectations of this specific intervention should include a reduction in screen time, increased physical activity and enjoyment, positive weight-related outcomes, and improved health. Often, positive expectations act as reinforcements and drive one’s behavior toward healthier habits. Likewise these expectations should encourage quality performance during the intervention.

Behavioral:

Reinforcement: Reinforcement is an outcome one’s behavior that is either positive or negative (NCI, 2005). This suggests that one’s priorities may influence or be influenced by their behavior and environment. Particular reinforcements that will be addressed in this intervention program will include improved health, family bonding, and time. Positive reinforcement will be provided as participants progress through the intervention replacing sedentary screen time with physical activity. Stickers will be given to track every 30 minute session spent physically active. Those who receive positive reinforcement may be more motivated to participate in the intervention and render better results.

Environmental:

Observational learning: This construct refers to the adjustment of behavior based on the observation of others’ behavior (NCI, 2005). In efforts replacing screen time with physical activity, children will most likely be influenced by the behavior of their parents. For this reason, it may be more beneficial for the program to engage not just the children but the family as a whole. The counseling sessions are designed to strongly encourage parental involvement and modeling throughout the 20 week intervention period in order to yield the most beneficial results. Other means of observational learning may occur by encouraging role models such as athletes, older siblings, peers, or community leaders.

Individual/Behavioral/Environmental

Reciprocal determinism: In the context of the Social Cognitive Theory, this construct is defined as the interaction that takes place between an individual, their environment, and their behavior (NIC, 2005). This intervention aims to alter unhealthy behaviors by manipulating the child’s household environment to increase social support, parental role modelling, and positive reinforcement as well as influencing the individual expectations of the child. Perceptions of physical activity are often linked to strategic exercise which may be perceived as strenuous and sometimes unachievable decreasing self-efficacy and successful behavior change. Changing these perceptions that exist within the individual is imperative to changing the environment and behavior of those participating in the intervention. According to this theory, behavior and environment have the ability to change these attitudes reciprocally as well. Families should be encouraged to enjoy physical activity rather than treating it as a chore and sedentary screen time should not be the primary means of family bonding occurring in the household.

I’m not sure how to improve the quality of the picture. It is also available as a PDF in the following link. SCT Concept Model 3

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

The target population for this intervention replacing sedentary screen time with physical activity will be children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 13 who have been considered overweight or obese by their primary care physician in the Athens Clarke County area. I have chosen to target individuals of this particular age range because the Community Guide reports that excessive amounts of screen time begin at age 8 in the United States and the Task Force recommends that interventions to reduce screen time begin by the time or before the child reaches age 13. I have chosen Clarke County because of its locality and the health disparities that exist here. Clarke County placed above the state average with approximately 28% of its children living in poverty in 2011 (NICHQ, 2011). Clarke County was also about the state average for days of air pollution due to particulate matter and ozone limiting opportunities for physical activity outdoors (NICHQ, 2011). Twenty-six percent of Clarke County adults are obese and 8.6% are living with diabetes (NICHQ, 2011). These characteristics indicate that there is room for improvement within the Clarke County community and reveal the disparities that exist among children. Food and nutrition expert, Caree Cotwright of the University of Georgia, noted it is imperative to target obesity at an early age citing that 80% of obese children remain obese into adulthood (Shearer, 2014). Children living in poverty are especially vulnerable to factors contributing to obesity including more distant geographic proximity to grocery stores, farmers markets, and various other healthy food outlets, increased likelihood of living in a single-parent household, and living in areas that limit physical activity. Factors such as these often give rise to greater consumption of highly processed foods, decreased physical activity, and social and/or psychological concerns among children, all of which may be contributors to childhood obesity. This intervention is designed to take place in the home so that children have the social support and modeling of improved behavior from a parent or caregiver.

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Increase behavioral capability of children and caregivers regarding the negative effects of excessive sedentary screen and the positive effects of physical activity by increasing knowledge of both in the counseling sessions | According to the Social Cognitive Theory, the perspective of the individual is guided by what he/she believes to be true and drives it drives their behavior and environmental interactions. Knowledge gained regarding the consequences of personal habits will most likely alter the attitude the individual has toward the behavior from positive to negative or vice versa or from harmless to detrimental. Values and priorities may also change as a result of increased knowledge. Providing information that is adjusted to match the comprehension of a child is more likely to be applied in daily life if parents are also well informed because they have a large influence on the environment of the child. | At the start of this intervention, children and caregivers will each receive a separate counseling session. The counseling session for the child will begin with coordinators requesting the participant report how long they watch TV on a typical day, their typical eating habits, and how much physical activity they take part in. The children will be able to visually assess their answers with the recommended amounts of each activity by coloring a graphic in which the two can be compared. After they are able to recognize the differences between their habits and the recommendations, the counselor will then go over the consequences of unhealthy behaviors such as lack of energy, weakness, and illness. They will also explain the benefits of healthy behaviors to include strength, endurance, and improved health while making an effort not to focus on physical appearance.

The parents’ counseling session will assess the same measures and contain the same content with the addition of items focused on emphasizing the importance of social support, parental modeling, positive reinforcement, and environmental barriers.

Both sessions will be combined and conclude with tips on how to apply healthier behaviors to their lifestyle as well as instructions regarding the “physical activity challenge,” the second phase of the intervention.

|

| Removing barriers to success and encouraging social support and modeling from parents (environmental adjustment) |

The Social Cognitive Theory suggests that the environment influences the behavioral decisions we make. Environmental contributors to behavior include access to resources, observation, and social support. By removing barriers to a successful intervention, the children are more likely to adjust and comply with intervention strategies. Involving parents and caregivers gives the children added social support during the intervention while also giving them a figure to model and observe throughout the program. | Participants will be assigned a “physical activity challenge” that will last for 20 weeks. Each week of the challenge, child participants will be tasked with achieving at least 15o minutes of physical activity. Parents will be instructed to remove TVs from their children’s bedroom. They will also be given a list of suggested games involving physical activity that they can do with their children during down time such as hopscotch, tag, hide and seek, etc. |

| Provide positive reinforcement to encourage changed behavior | The Social Cognitive Theory supports that self-efficacy is one of three major contributors to changed behavior. One’s confidence in their ability to change is imperative in their actual effort to do so. Providing clear goals that are realistic promote self-efficacy as the individual realizes that the objectives of the intervention are achievable. Providing positive reinforcement for achieving health goals builds greater motivation to continue the behavior. Confidence will also be promoted by engaging parents and caregivers in the intervention as well. Social support and observation of caregivers also changing health behaviors will also contribute to an increase in self-efficacy. | In their intervention packet, the family will be given a sheet where they can track their physical activity for the week using stickers. Each 30 minute session of physical activity will be awarded a sticker on their track sheet. If the child and family earn at least 5 stickers in a week (approximately 150 minutes of physical activity), they will be rewarded with a family movie night at the end of the week (or another family-oriented activity based on the child’s preferences and ability of the caregiver). |

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| Inputs for this intervention will include funding used to facilitate partnerships with local pediatric primary care physicians in order to gain participants who have been diagnosed as overweight or obese. Contact with the primary care physicians will be maintained after the intervention period in order to keep track of participant health outcomes. Funding will also be put towards the training and compensation of counselors or health promotion specialists who will carry out the counseling sessions with the children and their parents. Intervention tracksheets will also be produced and coupled with sets of stickers for used during the intervention. Counselling sessions will be carried out at a local community location such as a school classroom or recreation center. | Counseling session with both the children and their primary caregivers

Twenty week physical activity challenge Removal of environmental barriers such as bedroom televisions Require weekly rewards for meeting physical activity challenge goals |

Approximately 100 children will be participating in the intervention. We are expecting approximate 150-200 adult caregivers to participate as well. There will be 10 counseling sessions for both parents and children. The child sessions will have about 10 children per session and the adult session will have a range of 10-20 participants. Only one session is required. The sessions will be lead by a team of 10 counselors. Five will be assigned to children and the other 5 will be assigned to facilitate the adult sessions. Each participant will need an interactive worksheet to document their answers and draw their comparisons with the recommended values. There will be 300 of these worksheets available for the intervention. There will be 100 intervention packets available containing both the tracksheet, a set of stickers, a list of suggested physical activities, and a set of “rules” regarding the intervention challenge.

|

Success during intervention would be reflected immediately by an increase in positive reinforcement, observational learning, social support, and behavioral capability regarding replacing screen time with physical activity.

|

Success several months after the intervention would be reflected by an increase in weekly physical activity and a decrease in sedentary screen time. Time spent with family and self-efficacy to continued with improved behaviors would also increase.

|

Should participants persist with these changed health behaviors, rates of mortality, conditions, and disease associated with being overweight or obese would be significantly lower than that of a control group. Possible conditions avoided include, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and stroke. In addition to improved physical health, mental health may be improved based on increased levels of social support and self- efficacy.

|

Intervention Hypothesis:

Counseling sessions with children and caregivers will increase behavioral capability, observational learning, and social support in the household.

Requiring that parents provide rewards for accomplishing challenge goals will increase positive reinforcement for replacing screen time with physical activity.

Providing a physical activity challenge coupled with a weekly reward for accomplishing challenge goals, will increase positive reinforcement for replacing sedentary time with physical activity.

Removing bedroom access to television will increase observational learning and social support in the household.

Causal Hypothesis:

If this intervention is successful in effectively increasing behavioral capability regarding physical activity, utilizing positive reinforcement for improved health behavior, and encouraging social support and observational learning, then there will be a reduction in sedentary screen time as it is replaced with physical activity while there will also be an increase in self-efficacy and time spent with family.

SMART Objectives:

Goal 1: Increase positive reinforcement for replacing sedentary time with physical activity.

Objective: By the end of week 10, the caregivers and child reports of consistent weekly rewards in the household for meeting challenge goals will increase at least 75% from baseline measures.

Goal 2: Promote observational learning of improved health behavior.

Objective: By the end of the 20 week intervention, caregiver reports the presence of televisions in their child’s bedroom will decrease from baseline by at least 80%.

Goal 3: Promote social support for improved health behavior.

Objective: By the end of week 10, caregiver and child reports of weekly family-centered physical activity will increase at least 30% from baseline measures.

Goal 4: Provide family with behavioral capability to replace sedentary time with physical activity.

Objective: At the end of the 20 week intervention, caregiver reports of children managing their recommended physically active and sedentary screen time adequately and independently will increase from baseline reports at least 80%.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Child Participant | Primary participant in intervention | How will this intervention benefit me?

Is this the best way to go about solving my problem?

Are there any risks to participating?

How will this intervention change my health behavior? |

Decreased sedentary screen time

Increase in physical activity

Increased levels of social support and self-efficacy |

Unchanged health behaviors

Unchanged amounts of sedentary screen time and physical activity

Increased risk of mortality and morbidity associated with being overweight or obese |

| Primary Caregiver | Cares for child participant

Facilitates intervention in the household

Provides positive reinforcement for healthy behavior changes |

What is my role in this intervention?

How will this benefit my child and my household?

Are there any risks to my child participating?

What will this intervention cost?

How can I assist my child in the intervention?

|

Potential savings in health care costs

Increased social support within family

Increased health outcomes for child

Improved family health behaviors |

Increased health care costs as unhealthy behaviors in child continue

Unchanged social support within family

Increased health risks for child

Unchanged family health behaviors |

| Primary Care Physician | Provides medical and preventive services to child participant

Informs caregiver of health risks and ways to mitigate them |

How will this intervention be tailored to my patient?

Will the intervention properly address the needs of my patient?

Will my patient and their caregiver be willing to participate in the intervention?

Are there any risks to my patient participating?

What are the expected health outcomes of the intervention for my patient? |

Healthier patient base

Caregivers more involved in health behaviors of patient

Less diagnoses of conditions associated with being overweight or obese

More knowledgeable and health conscious patients |

Decreased health of patient base

Increased diagnoses of conditions associated with being overweight or obese |

| Program Coordinators | Implement intervention

Provide counseling sessions

Provide intervention packet

Follow up with participants to track progress and behavior changes

|

Is this intervention financially feasible and realistic?

What outcomes do we expect to see as a result of this intervention?

How will we deliver the counseling sessions in a way that is applicable and easily understood? How can we facilitate successful interventions?

How will we measure participant progression and the effectiveness of the intervention?

|

Continued use of the intervention to alter health behaviors in overweight or obese children and adolescents

Increase the number of participants based on funding capabilities |

May be required to modify intervention based on the components that most likely contributed to its failure

May develop an entirely new intervention that eliminates weaknesses of the previous intervention |

To evaluate the outcome of the intervention, a group randomized control design will be used with a treatment group and a control group. The treatment group will be assigned the intervention program and the control group will not be manipulated in any way. After primary care physicians have selected their patients who are eligible for the program based on age and health status, they will be given the option to participate with informed consent and randomly assigned into either the treatment or control group to eliminate differential selection bias. There will be a pre-test administered to both groups prior to the start of the intervention. There will also be two post-tests which will be administered to both groups as well at 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and then at 6 months. The tests will be used to gauge the individual’s typical habits related to physical activity, sedentary screen time, levels of social support, self-efficacy, and household environment.

R O1 X O2 O3 O4 (Treatment Group)

R O1 O2 O3 O4 (Control Group)

O1: pre-test O2: post-test at 10 weeks O3: post-test at 20 weeks O4: post-test at 6 months

Threats to Validity

Maturation:

Maturation is significant threat to the validity of the intervention mainly due to the age of the participants. Participants of the study will range between the ages of 8 and 13. Significant physical and behavioral changes at these ages may be due to the onset of puberty. Also occurring at these ages are the transition from elementary school to middle school where school-based sports activities are more common. Consequently, changes in time spent engaged in physical activity may be due to the change in school environment rather than the intervention. To attenuate these threats, we will assess the same processes in the comparison group which should similar demographically to the treatment group.

Attrition:

Because this evaluation design contains more than one group, attrition poses a significant threat to its validity. Should participants drop out, the evaluation data may be skewed. To attenuate this threat, the primary care provider of the children and adolescents will help facilitate participation to better ensure that candidates are local resident who are generally concerned about their health status and their involvement is recommended by their physician. Results due to attrition can be further managed by administering multiple tests to the groups at varied points in time.

Testing Bias:

Testing the groups before and after the intervention may be a threat to the validity of the evaluation because answers will be self-reported. Having had the pre-test, individuals may be more inclined to adjust their answers on the following post-tests based on what they would expect to report after the intervention. Self-reported data always has the possibility of being biased and an inaccurate depiction of the individual’s actual reality. This threat will be attenuated by the two group design because both groups will have the same exposure to the pre-test and have the same chance of becoming sensitized to it.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Individual:

Increased self-efficacy regarding health behavior Increased behavioral capability Increased enjoyment of physical activity

|

The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) (Moore et al., 2009) | The PACES scale was originally developed to assess the enjoyment of physical activity among adults and was later modified to assess the same in children. The scale provides a stem question followed by a variation of 16 responses in which the child is able to choose the answer that best fits their perception. (Moore et al., 2009)

|

When I am physically active…

|

Scores of the PACES correlated significantly with other observed measures which included athletic competence, physical activity reports, and task goal orientation. Internal consistency is support by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90 and item-total correlations ranging from 0.38 to 0.76. (Moore et al., 2009)

|

| Behavioral:

Increased physical activity Increased reinforcement for improved health behaviors Decreased sedentary screen time

|

Children’s Leisure Activity Study Survey (CLASS) questionnaire (Telford et al., 2004) | The CLASS questionnaire was designed to examine physical activity during the week and weekends among children age 10-12. The questionnaire has two parts, the proxy report for the caregiver and the self-report for the child. The survey assesses the household demographics and the time and frequency spent engaged in specific physical activities throughout the week. The proxy and self-report questionnaires are identical. Responses are given by circling “yes” or “no” to a list of physical activities that the child engages in along with the time and frequency if circled “yes”. (Telford et al., 2004) | “Does your child play basketball during the week days? If yes, how long and how often does your child play basketball?”

The questionnaire would be modified for this intervention to assess types of sedentary activities the child engages in as well as the frequency and duration of those activities. |

The percentage agreement between the proxy and self-reported items ranged from 62% to 94%. Thirteen retest correlations for frequency and duration of physical activities were at or above 0.45 while the correlation for overall physical activity reports were low. Reliability analysis of the reported demographics showed little to no differences. There was some differences in the reliability of reports based on demographics but validity was not significantly affected by factors other than age where it was less satisfactory among younger children. (Telford et al., 2004) |

| Environmental:

Increase in social support Removal of barriers to healthy behaviors Increase in observational learning

|

ASAFA Scale (de Farias Junior et al., 2014)

|

This scale analyzes the support children and adolescents receive from family and friends in terms of stimulating, practicing, watching, asking, commenting, carrying, and transporting. The Likert scale is used to assess the frequency of each action during a typical week. There are 12 different items total, six are used to assess the social support of parents and six are used to assess that of friends. (de Farias Junior et al., 2014)

|

How often do your parents do physical activities with you? Never, Rare, Frequently, or Always

|

Internal consistency was satisfactory according to Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (alpha> 0.77 among parents, alpha>0.87 among friends) and the Composite Reliability (CR > 0.83 among parents, CR>0.91 among friends). Significant differences were not observed across varied demographics. A significant association between the adolescents’ physical activity and reported social support of parents (rho=0.29) supports construct validity for the scale. (de Farias Junior et al., 2014) |

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

a. Recruitment and Enrollment

We will utilize the primary care offices we partner with to facilitate enrollment of eligible participants. Patients who meet the intervention criteria for age and physical health status will receive an invitation by mail to participate in the program. Should they decide to participate or would like more information on the details of the intervention, there will be an information session 3 weeks prior to the start of the intervention where official enrollment will take place with informed consent.

Invitation to Enroll:

Dear (Parent/Caregiver Name),

You are receiving this letter because your child’s primary care physician has recommended your participation in a behavioral intervention to replace sedentary screen time with physical activity. Based on your child’s current physical health and age, he/she meets the eligibility criteria to participate and your physician believes this intervention may be a valuable investment in your child’s health.

This intervention will assess your child’s typical behaviors, perceptions, and environment to establish a baseline measurement. Once the intervention begins, separate counseling sessions will be provided to both you and your child to increase your knowledge on recommended health behaviors and guide you to applying those behaviors in the household. The counseling sessions will be followed by a 20 week health challenge in which the ultimate goal is to significantly replace sedentary screen time with physical activity. Upon completion of the program, we will follow up with your progress two months afterward.

If you and your child would like to take part in this intervention or would like to learn more about it we will be hosting an information session on Monday, September 5th, 2017 at 6:00pm. This session will go into further detail regarding the intervention process as well as give you the opportunity to officially enroll in the program with informed consent. If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to contact the program coordinators at (706) GET-ACTV or getactiveathens@uga.edu.

Sincerely,

Chelsea Lewis

Program Coordinator

Get Active Athens

Enrollment Track Sheet (For internal use only)

| Name | Parent Name | Age | Gender | Primary Care Physician | BMI | Current Health Diagnosis | Phone Number | Current Address |

b. Attrition

Attendance at all parental counseling sessions will be taken with a sign in sheet. Attendance at the children’s counseling sessions will be logged by program coordinators immediately before the session begins. To track attrition of participants, program coordinators will make frequent phone calls to the primary caregiver or parent of the participants every two weeks to verify their participation, intent to complete the intervention, and if they have previously discontinued their participation at any point. Their responses will be documented for internal tracking.

Attrition Tracking Sheet (For internal use only)

Date: _________________

| Primary Caregiver Name | Current participation verified? | Intending to complete? | Discontinued at any point? If yes, when? |

| Doe, John | Yes | Yes | Yes, Day 34-36 |

| Ralph, Lauren | Yes | Yes | No |

| Trump, Donna | No | No | Yes, Day 42 |

c. Fidelity

To track fidelity in the household during the 20 week program challenge, frequent phone calls will be made every 2 weeks to ensure that positive reinforcement is utilized correctly, parents are role modelling, suggested environmental changes in the household have occurred and persist, and physical activity is correctly documented.

Household Implementation Sheet:

| Primary Caregiver Name | Behavior rewarded weekly? | Participating with child ? | TV in child’s bedroom? | Utilizing intervention track sheet? |

In order to track whether the intervention is properly implemented during the counseling sessions, those who are leading the sessions will be provided with a list of items to cover and a guide in how they should be delivered. This ensures that each counseling session is identical in content and delivery.

Counseling Session Guide:

- Current Habits vs Recommendations

- PARENTAL SESSION: Allow participants to answer all questions regarding typical household behaviors prior to revealing the recommended behaviors

- CHILD SESSION: Present child with folded handout, with the graphic representing the recommendations facing down on the table. Allow child to color all graphics according to their typical household graphic before unfolding to reveal recommendations.

- Share consequences of unhealthy behavior

- PARENTAL & CHILD SESSION: Consequences to address will include lack of energy, weakness, and illness. Adjust language and tone to suit audience. Make effort not to focus on physical appearance

- Share benefits to healthy behavior

- PARENTAL & CHILD SESSION: Benefits to address will include endurance, strength, improved mental and physical health, and potential for family bonding. Adjust language and tone to suit audience. Make effort not to focus on physical appearance.

- Suggested Application

- PARENTAL SESSION ONLY: Share the positive influence of social support, observational learning, and environmental changes in changing health behavior.

- Emphasize role modelling, positive reinforcement, removing bedroom TVs, and verbal encouragement

- Challenge Initiation

- BRING PARENTS AND CHILDREN TOGETHER

- Supply parent with intervention packet including tracksheet, suggest physical activities, stickers, and intervention rules.

- Go over rules and expectations

- Allow parents and children to agree to positive reinforcement method

- Allow time for questions before dismissal

- PARENTAL SESSION ONLY: Share the positive influence of social support, observational learning, and environmental changes in changing health behavior.

Rules will be provided in the intervention packets that are distributed to the parents. These will guide participants to implement the intervention in the household the way it is intended.

GET ACTIVE ATHENS CHALLENGE RULES:

- If present, televisions in the child’s bedroom must be removed for the entire intervention period.

- Tracksheets must be utilized to document physical activity. Every 30 minutes of physical activity will receive one sticker.

- At the end of each week, the child must have received at least five stickers (150 minutes of physical activity) to receive their reward.

- Parents must supply reward for weekly goal completion.

*Parents are strongly encouraged to participate in physical activities with child when possible.

GET ACTIVE ATHENS TRACK SHEET (For participant use during intervention):

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | If I get 5 stickers this week, then we get to… |

Andrade, S., Verloigne, M., Cardon, G., Kolsteren, P., Ochoa-Avilés, A., Verstraeten, R., & … Lachat, C. (2015). School-based intervention on healthy behaviour among Ecuadorian adolescents: effect of a cluster-randomized controlled trial on screen-time. BMC Public Health, 15942. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2274-4

de Farias Junior, JC, Medonca, G, Florindo, AA, de Barros, MV. (2014).Reliability and validity of a physical activity social support assessment scale in adolescents—ASAFA Scale. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17 (2), 355-370. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4503201400020006ENG

Maddison, R., Marsh, S., Foley, L., Epstein, L. H., Olds, T., Dewes, O., & … Mhurchu, C. N. (2014). Screen-Time Weight-loss Intervention Targeting Children at Home (SWITCH): a randomized controlled trial. The International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, 11111. doi:10.1186/s12966-014-0111-2

Moore, J. B., Yin, Z., Hanes, J., Duda, J., Gutin, B., & Barbeau, P. (2009). Measuring Enjoyment of Physical Activity in Children: Validation of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale. Journal Of Applied Sport Psychology, 21116-129.

National Cancer Institute, (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.aub.edu.lb/fhs/heru/Documents/heru/resources/pdf/TheoryataGlance.pdf

National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (2011). Healthy lifestyles in Clarke County, Georgia. Retrieved from http://obesity.nichq.org/resources/obesity-factsheets

Shearer, L. (2014, October 24). Georgia making strides to lessen childhood obesity, but more still to do. Retrieved from http://onlineathens.com/health/2014-10-23/georgia-making-strides-lessen-childhood-obesity-more-still-do

Telford, A., Salmon, J., Jolley, D., & Crawford, D. (2004). Reliability and Validity of Physical Activity Questionnaires for Children: The Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey (CLASS). Pediatric Exercise Science, 16(1), 64-78.

Yilmaz, G., Demirli Caylan, N., & Karacan, C. D. (2015). An intervention to preschool children for reducing screen time: a randomized controlled trial. Child: Care, Health And Development, 41(3), 443-449. doi:10.1111/cch.12133