Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

- Summarize the recent evidence for or against the intervention strategy in a table. (28 points)

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Baker, et al., 2014 | This intervention was conducted at the Erie Family Health Center (EFHC) in Chicago which uses the General Electric Centricity electronic health record (EHR). The EHR has clinical reminders and services that allows collection of data for quality of care purposes. Patients that are due for a repeat fecal occult blood test (FOBT) are found through their EHR system and then randomly assigned to either receive usual care or receive a “multifaceted intervention.” | The eligibility criteria included being 51 to 75 years of age, listing preferred language as English or Spanish, and receiving a negative FOBT result between March 1, 2011, and Feb 28, 2012. The study excluded those who had a colonoscopy in the past 10 years or flexible sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, or those who had any medical conditions that might make FOBT “inappropriate for CRC screening.” 450 patients were eligible for the study and 225 were randomly placed in each group. 23 patients in the intervention group were not given the intervention because they completed a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) prior to their due date. 72% of the participants were female, the average age of the participants was 60, the majority identified as Latino/Hispanic with their preferred language as Spanish, more than 3/4 were uninsured, and about 2/3 had 1 or more chronic conditions. | The main outcome that was measured was the completion of the fecal occult blood test (FOBT), a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening modality, within 6 months of the data the patient was due for annual testing. | The patients in the intervention group were more likely to complete the FOBT than those that received usual care “(82.2% vs 37.3%; P < .001).” 10.2% of the 185 intervention participants completed screening before their due date and therefore did not receive the intervention. 39.6% of participants got screened within 2 weeks of the initial intervention, 24.0% between 2 to 13 weeks after the second and third step of the intervention, and 8.4% within 13 and 26 weeks after the fourth and also last step. Therefore, the intervention caused a significant increase in participation in annual CRC screening as most patients participated in screening before the last step of the intervention. | 3 months after initial contact.

|

| Kerrison, et al., 2015 | The intervention setting was the London Borough of Hillingdon (LBH), a location that routinely fails to reach European target’s for attendance in breast cancer screening. The control group comprised of women that were invited to breast cancer screening without any reminders, as usual. The women assignmed to the intervention group received the same invitation to the screening appointment as the control group, and also received a text message reminder 48 hours before their appointment. | The eligibility criteria included women aged 47-53 that were invited to their first routine breast screen in the LBH during the study period (November 2012–October 2013). 2294 women were enrolled in the trial. 54 opted out of the trial. Therefore 2240 women were included. 1118 were randomly assigned to the control group, and the other 1122 were to the assigned to the group receiving the text-message reminder. | The outcome variable measured was the patients’ attendance of their initial breast screening appointment and their attendance within 60 days of their initial appointment. | Breast cancer screening attendance was 59.1% in the control group receiving usual treatment and was 64.4% in the group that received the text message intervention. “(95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.05-1.48, P=0.01).” Only 456 of the women in the intervention group were actually sent a text message because only those that had a cell number recorded by their GP received a text message. In an analysis that analyzed the ideal patients (those that had a cell number on file), 59.77% of the control group attended the screening and 71.1% of the intervention group attended “( 95% CI=1.29-2.26, P<0.01).” Therefore the text message intervention performed prior to the first breast screening appointment greatly increased attendance. | A follow-up occurred 60 days after the initial appointment was offered. |

| MacLaughlin, et al., 2014 | The intervention setting was Mayo Family Clinic Northeast (NE) and Mayo Family Clinic Northwest (NW) in Rochester, Minnesota. Internally developed information systems were used to identify eligible women, those due for cervical cancer screening, for the study. The group that received the intervention, those that were employees or dependents of employees (E/D) at the Northeast clinic site, was sent one reminder letter. Those patients who already had a scheduled appointment were not sent a reminder letter. | Patients in the Northeast (n = 1613) and Northwest (n = 1088) clinics were divided into two groups, those with a history of “overdue/unknown screening status” (NW, n = 728; NE, n = 1106) and those historically compliant, defined as patients that had received a pap test 3 years and 3 months prior to the study start date(NW, n = 360; NE, n = 507). Next, the patients that were E/D were identified (NW, n = 544; NE, n = 795) as well as those that were not (NW, n = 544; NE, n = 818). Those 795 patients that were at the Northeast clinic and E/D patients were put in the intervention group. The patients that already scheduled appointments were not sent the intervention letters. Over the course of the study, 564 patients were sent letters. 1906 other patients were placed in the control group. | Cervical cancer screening rates were measured for each of the groups, those participating in the letter intervention and those that were not participating in the intervention. | The screening rate for the E/D group was higher than the non – E/D group at both clinics “(32.7 versus 18.2% at NW, P < 0.001; 39.0 versus 14.7% at NE, P < 0.001).” Unadjusted screening rates for the historically compliant group were higher for the E/D patients at the Northeast clinic which received the intervention letters than the E/D patients at the Northwest clinic who didn’t receive the letters “(56.1 versus 44.5%, P = 0.01).” There was no difference observed between those in the group with a history of “overdue/unknown screening status” “(27.4 versus 25.9%, P = 0.62)” or in the screening rates of non- E/D subjects at either clinic for both compliant “(24.2 versus 30.6%, P = 0.18)” and “overdue/unknown screening status” “(11.9 versus 13.0%, P = 0.59)” patients. According to the results of this study, reminder letters improve the screening rates for cervical cancer in patients with a history of compliance to screening and appear to have no measurable effect if the patients’ screening is overdue. | 2 months after the last reminder letter was sent. |

- Explicitly state the updated recommendation(s) for the selected strategy(ies). You should have a statement declaring whether the strategy is Strongly Recommended, Recommended, Not Recommended or there is Insufficient Evidence to make a recommendation. (5 points)

The strategy selected is using reminders to clients to increase cancer screening. The Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends this strategy specifically for breast and cervical cancers as well as for colorectal cancer with fecal occult blood tests (FOBT). Although the Task Force has found strong evidence that the strategy is effective for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer, it has found insufficient evidence for other types of cancers as well as for other testing methods for colorectal cancer besides FOBT. In addition, the Task Force has not identified any harms of using client reminders in any of the literature and neither has the systematic review team. The Task Force has updated their recommendation since their first recommendation and its recommendation has remained consistent in that the evidence supporting the positive effect of the strategy for breast and cervical cancers as well as colorectal cancer with FOBT has increased as well as the evidence for other tests and cancers has remained insufficient. My updated recommendation based on the evidence provided through the three articles in the above chart is “Recommended,” which is consistent with the current recommendation of the Task Force.

- Justify your recommendation. Identify whether there were any changes to the recommendations. For example, did you change one of the recommendations from “insufficient evidence” to “recommended”? Explain why or why not based on the evidence. (12 points)

I did not change the recommendation from “recommended” to “strongly recommended” because all three of the articles mentioned that further research and follow up must be done. For example, in the article by MacLaughlin, et al., more research needs to be conducted using women whose screening rates are typically overdue/unknown. The article by Kerrison, et al. mentions that a randomized clinical trial with a larger sample size of women with mobile phone numbers is needed in order to test the hypothesis that text messages to women prior to their breast cancer screening appointment increases attendance rates in deprived areas. The article by Baker, et al. mentions that their study has limitations that may make their findings un-generalizable, including small sample size and an unexpectedly stable population. However, I also did not change the recommendation from “recommended” to “insufficient evidence” because the Task Force has found significant evidence that demonstrates that there is a positive association between the strategy and the screening rates, and also because all three of the articles included in the above chart support the strategy and support the Task Force’s current recommendation. I also didn’t change the recommendation from “recommended” to “not recommended” because in each of the articles, the screening attendance rates for the intervention group were higher than that of the control group that received usual care, therefore demonstrating the positive effect of client reminders on cancer screening.

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

- Briefly describe in text the theory you selected, including each of the constructs, and why. You may reference evidence from your table above or other sources. (20 points)

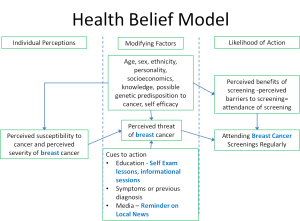

The Health Belief Model (HBM), one of the earliest and most recognized theories about health behavior, was first developed to explain the lack of people working to control their health (NCI, 2005). Cancer screenings are programs that are implemented widely and encouraged for certain demographics of people to prevent or catch cancer before/after it becomes serious. Chronic conditions such as cancer have gradually become more prevalent than infectious diseases in many developed countries such as the United States. They are often much more difficult to treat and can cause many other problems for people who have the disease as well as the affected person’s family and friends. Despite cancer being a disease that is difficult to treat, cancer screening attendance is not optimal. We can use the Health Belief Model to explain what encourages or discourages people from attending screenings.

There are six main constructs to the Health Belief Model (NCI, 2005). They affect each individual’s choices regarding whether to prevent and control disease. In this situation, the constructs influence whether or not an individual attends their breast cancer screenings to prevent disease. Self efficacy is not one of the constructs; however, it is one of the intervention methods because increasing self efficacy has a positive effect on the accuracy of perception of breast cancer screenings.

Constructs

Perceived Susceptibility & Perceived Severity

The first construct is “perceived susceptibility” which in this case is an individual’s beliefs about his/her chances of getting breast cancer. The second is “perceived severity.” This construct identifies whether or not an individual believes breast cancer has serious consequences. Some people who have/had a relative with cancer may have seen that cancer causes severe pain, emotionally and physically, and therefore may perceive breast cancer to be very harmful. Others, on the other hand, may have had a relative that recovered from cancer quickly and therefore may feel that the severity of cancer is not too high. The two constructs of perceived susceptibility and perceived severity describe an individual’s perceptions of the disease, which in this case is breast cancer.

Perceived Barriers

The next three constructs can be thought of as modifying factors to an individual’s perceived threat of the disease. The first of these three is the construct “perceived barriers,” which are an individual’s perceived costs to completing an action (NCI 2005). In this case, examples of perceived barriers to attending cancer screenings are the cost of insurance, the cost of copay, and transportation to the screening.

Perceived Benefits

The next of the modifying factors is “perceived benefits,” which can be defined as an individual’s belief that their actions will decrease the risk/severity of disease, such as an individual’s belief that a cancer screening will accurately/effectively decrease his/her risk/severity of cancer. An individual’s personality, self efficacy, age, family history of cancer, and other factors can contribute to his/her perceived benefits/barriers of attending cancer screening. If an individual perceives the barriers to be greater than the benefits, he/she may be discouraged from the action.

Cue to Action

The last of the modifying factors is “cue to action,” which as it sounds, is factors that prompt/stimulate action. Examples of cues are media campaigns on the benefits of cancer screenings, education about an individual’s risk of cancer, and reminders such as text messages or letters in the mail to attend a cancer screening.

Likelihood of Disease

These five constructs all play a role in the sixth construct which is the perceived likelihood of disease. Depending on how high the perceived likelihood of disease is, the individual is more or less likely to take steps to prevent the disease, such as attend their cancer screenings regularly. The Health Belief Model helps health practitioners to design strategies and programs that alter behavior in a positive manner specifically through understanding and changing the population’s perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived barriers, and perceived benefits (NCI, 2005).

- Draw a diagram to illustrate your conceptual model, making sure to include an indication of the hypothesized direction of the relation (positive or inverse) between the constructs. You may use plus or minus signs, up and down arrows, or another method as long as it is clear. Do not create a logic model. (16 points)

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

- Briefly describe the target population and program setting for your intervention. Think about the course materials and discussion of health disparities. Provide evidence for why your target population is a health disparate group. This can include, but is not limited to, description of greater risk or prevalence of disease or risk factors, being in a minority group or low-resource geographic area. Provide citations as appropriate. (6 points)

The target population for the intervention is African American/Black women from low socioeconomic regions, who are one of the groups that face the greatest burden of disease in regards to cancer (American Cancer Society). The program setting for my intervention is a clinic in a neighborhood with a low socioeconomic status and low available resources. These regions have low rates of cancer prevention and screening. According to the CDC’s breast cancer rates by state, one of the regions with the highest concentration of breast cancer rates is the southeast/middle region of the United States. Therefore, a town within that region will serve as the intervention setting. Specifically the intervention will involve sending patients reminders for breast cancer screenings. African American women have a higher rate of breast cancer mortality than non-Hispanic white women despite having a lower breast cancer incidence rate (American Cancer Society). This may be an indication of lower rates of screening for breast cancer causing the cancer to be caught at a much farther along state.

- Explicitly state the Intervention Methods for the program, the theory from which they are derived, and a brief description of how they align with that theory. Use the Table template below. (12 points)

- Explicitly state the Intervention Strategies for the program and explain which strategy will be used with each method. Enter this information into the table below. (15 points)

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Increase knowledge and awareness of breast cancer and screening and their effects | The first two constructs of the Health Belief Model are perceived susceptibility and perceived severity. Individuals may have an incorrect perception of their need for screening which can cause a disease to go undiagnosed. For example, younger women may believe that they have nothing to worry about regarding breast cancer despite the fact that they are still at risk, even though that risk is lower than for older women. If an individual has an incorrect perception of their risk of breast cancer or the severity of the disease, they may put off screening until it is too late. Education and awareness can be used in order to educate people on the perceived susceptibility of each individual. | Some individuals, through influence of their culture or other reasons, believe mammograms can cause cancer. Beliefs such as these that are incorrect can be changed through educational programs and informational sessions held at clinics and schools that provide education about an individual’s risk of cancer as well as cancer itself. These informational sessions will be the most effective if they are held by trained health professionals from the community who understand the culture. Brochures and flyers placed strategically in highly populated areas will also help to raise awareness. Another tactic to educate people is personal testimonies and media campaigns, for example, through live performances, radio, or television. |

| Increase access to breast cancer screenings

|

Another construct of the Health Belief Model is perceived barriers. For the target population in this intervention, which is African American women in low socioeconomic regions, there may be barriers to them accessing the cancer screenings such as the cost of insurance, the cost of the copay, and transportation to the screening. In order to counteract many of these barriers for the women in this setting, change must be made on a policy level targeting health insurance as well as the built environment such as infrastructure. | For many women in low socioeconomic regions, there may be physical and economic barriers to reaching cancer screenings. These may include costs of transportation, insurance, healthcare, or other costs involving screenings. Policy change must be made in order to make access to cheaper options available and more options for public transportation. |

| Promote self efficacy | Another construct of the Health Belief Model is perceived benefits. An individual may believe that their benefits from attending a cancer screening are lower than the barriers/cost associated with the screening, discouraging them from attending. Besides awareness and education being done to increase knowledge of the benefits, self efficacy can also play a role in educating/demonstrating the importance of cancer screening and can decrease perception of barriers by showing individuals that they can take action themselves on a regular basis. | Self efficacy can be promoted through educational workshops held by health professionals from the community that teach women how to perform self breast exams on themselves. Women can then regularly check themselves and feel more empowered to protect and prevent themselves from disease as well as feel less intimidated by the barriers they associate with cancer screening. In addition, these workshops can teach women about the benefits of screening. |

| Stimulate action | Cue to action is another construct of the Health Belief Model. Sometimes, even if an individual has education and knowledge about the benefits of screening, they may forget about their appointment. When an individual is healthy, steps to prevent disease may not be on their mind and media and other ways may help to keep it fresh on their mind. | Cues to action can be media campaigns on the benefits of cancer screenings, reminders such as text messages or letters in the mail to attend a cancer screening, and flyers and brochures on screenings. |

- Provide the logic model for the program as a schematic. (25 points)

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| For example, funding sources, space, personnel

The funding sources can be government grants, space can be local clinics and possibly schools, and personnel can be nurses, doctors, and other health professionals from the community, either paid by grant money or volunteers. Schools and clinics can be the sites of educational workshops/sessions. The clinics and hospitals can be sites of actual breast cancer screenings. |

This column should include your Intervention Strategies from Table 2.

The strategies include a media campaign that takes advantage of the local news stations, educational/informational seminars, educational workshops teaching women how to conduct self examinations, and policy changes increasing access to breast cancer screenings. It also includes sending individual text messages to each individual patient in the intervention group. |

For example, # of brochures or pamphlets distributed, # of educational sessions, # of lay health outreach workers trained

The number of brochures or pamphlets distributed will be about 5,000 and the number of educational sessions will be about 20 held in different places throughout the city. The number of lay health outreach workers that will be trained will be around 100, about 25 from each of 4 different clinics within the region because the intervention will heavily rely on already trained health professionals from the community. In addition, there would be a segment/reminder on a local news channel reminding women to attend breast cancer screenings. |

This should link to your theoretical model. For example, if you selected Theory of Planned Behavior, you should want to change attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in addition to any other short-term outcomes

The short term outcomes from this will be that the perceived severity and susceptibility of breast cancer and breast cancer screening will be accurate, the perceived benefits of attending the screenings will be higher, the perceived barriers will be lower relatively (or even if they aren’t perceived to be lower, the hope is that the perceived benefits will be higher than the barriers), and that the cue to action will inspire more people to attend their screening. In addition, self efficacy will be increased. |

Your health behavior(s) of interest

Increased breast cancer screening attendance rates. |

The mortality, infectious or chronic disease outcomes associated with the health behavior(s) of interest; may also include quality of life indicators

Lower mortality rates for breast cancer, as well as greater rates of the population with health insurance and access to health care facilities. |

- Explicitly state the causal and intervention hypotheses. You should have an intervention hypothesis linking each item in your activities to one or more short-term outcomes, and a causal hypothesis linking each item in short-term outcomes to at least one intermediate or long-term outcome. (12 points)

Intervention hypothesis example format: [Intervention activities] will lead to increases/decreases/improvements in [health behavior].

Causal hypothesis example format: Increases/Decreases/Improvements in [short-term outcome] will increase/decrease/improve [intermediate or long-term outcome].

Intervention hypothesis:

Media campaigns will increase the awareness of breast cancer screening and its benefits.

Educational/informational seminars and flyers will help increase awareness of the benefits of breast cancer screening and help provide a support network and knowledge of health professionals for women.

Educational workshops will help increase self efficacy for women by allowing them to learn how to self examine themselves, as well as train more health professionals to conduct screenings that are tailored to individuals, also teaching them their specific perceived susceptibility. Increasing patients’ self efficacy will lower perceived barriers by making taking control of prevention much less intimidating.

Individual text messages and letters will remind women of their screening appointments, increasing the short term outcome of cue to action.

Policy changes will make more public transportation accessible, allowing more women to reach their screenings.

Causal hypothesis:

The lack of attendance of women for their breast cancer screening appointments is due to a lack enough screening locations, a lack of trained health professionals to conduct the screenings, a lack of access to screening locations, a lack of awareness of the benefits of attending screenings, and a lack of perceived susceptibility and severity of breast cancer. Increases in breast cancer screening attendance rates will, in the long term, decrease breast cancer rates. Providing the patients with support and self efficacy will lower the long term outcome of breast cancer mortality rates by catching disease earlier on in development.

State the SMART outcome objectives for your program. At minimum you should have a SMART objective for each outcome in your short-term outcomes and your health behavior(s) of interest from your logic model. Your SMART outcome objectives should link back to the theoretical construct/behavior/risk factor you want to change with your intervention strategies in Item 8. (10 points)

Goal 1: Increase accurate perceived severity of breast cancer among women including in this intervention and awareness of .

- Objective 1: At the end of the educational sessions, at 20 weeks, 50% of participants will pass a knowledge test on breast cancer mortality prevention with at least a 70%.

Goal 2: Increase accurate perceived susceptibility to breast cancer in women in this intervention.

- Objective 1: At the end of the educational workshops/trainings, at 15 weeks, health professionals will pass a knowledge test with at least a 70% of what increases an individual’s susceptibility to breast cancer and how to communicate with patients in an effective, personalized way.

Goal 2: Increase the perceived benefits of attending breast cancer screenings among women in this intervention.

- Objective 1: At the end of the 20 weeks of educational sessions and workshops, the number of women reporting in a survey the knowledge of general as well as personal benefits of screening will increase by 25%.

Goal 3: Decrease the perceived barriers of attending breast cancer screenings for women in this intervention.

- Objective 1: At the end of the 20 weeks of educational sessions and workshops, the number of women reporting in a survey that they feel that barriers to screening are higher than benefits will decrease by 25%.

Goal 4: Increase self efficacy.

- Objective 1: At the end of the 20 weeks of educational workshops, there will be a knowledge test that will evaluate whether or not the participants feel comfortable conducting a self exam and whether or not they know how to conduct the self exam.

Goal 5: Increase breast cancer screening attendance rates by patients at clinics included in the intervention through cues to action and education.

- Objective 1: At the end of the 20 weeks of educational sessions and workshops and flyers, the attendance rates of breast cancer screenings will increase by 30%.

Goal 6: Decrease breast cancer mortality rates in the region included in the intervention.

- Objective 1: At 1 year after this intervention, the rates of breast cancer mortality will decrease by 1%.

- Objective 2: At 2 years after this intervention, the rates of breast cancer mortality will have decreased by a total of 2%.

- Objective 3: At 3 years after this intervention, the rates of breast cancer mortality will decrease by 3%.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

- State the major stakeholders of your project, evaluation questions each stakeholder may want answered about the project, and how each group of stakeholders might be affected by the evaluation outcomes? Be sure to consider any individual or group who you list on your Inputs column of your logic model. (16 points)

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Health Professionals-nurses, doctors/Educators | Their role is implementing the intervention. These are the individuals that have to administer screenings as well as hold the educational and informational sessions. In addition, they may be consulted when putting together the media campaigns. These health professionals will also be responsible for sending out reminders to patients of their upcoming breast cancer screening appointments. These health professionals will also take a knowledge test. | How much time and resources will we be investing in this program? What will be our role in the program? How effective will the program be? How will we convey the skills and knowledge to the program participants effectively? Will we be compensated for what we invest in this program? | The health professionals and educators will be able to effectively communicate information about breast cancer screenings and confidently teach women how to self examine themselves, increasing self efficacy. They will also have the drive to continue implementation of a version of the intervention, maintaining funding and participation. | The health professionals lose the desire to participate in future programs and do not gain the ability to effectively communicate the skills and knowledge included in the program goals, either due to a lack of resources or a lack of adequate training. |

| Women in the region of intervention | The women are participants that are served by the program. The role of the women included in the intervention will be attending their breast cancer screening appointments as well as the educational workshops and information sessions, if they can. The women will also receive the reminder letters and text messages. In addition, they will take a survey and knowledge tests. | How will my participation in the intervention affect my risk of breast cancer mortality? What skills will I get out of the intervention? What knowledge will I gain from the program? Will my clinical visits for screening appointments improve or change in any way because of this program? Will my costs for screening change? | Increase in breast cancer screening rates and decrease in breast cancer mortality rates. Increase in awareness and accurate knowledge of the benefits of breast cancer screenings. | Unchanged breast cancer attendance rate and unchanged rates of breast cancer mortality.

|

| Government | The government will help provide the funding for the implementation of this program. The government’s role in this intervention is also that they be responsible for carrying out the policy changes necessary to make public transportation, and therefore screenings, accessible for a larger percentage of the population. In addition, the government will be a source of funding through grants. | Will the funds invested be effectively used? What is the cost benefit for the program? Will the program effectively increase breast cancer screening attendance? | The government will continue to fund more cycles of this intervention and remain open to greater policy change to allow the program to be accessible to a large number of women. | The government will halt or slow their funding for interventions of this nature in the future if this intervention does not prove to be effective in increasing breast cancer screening attendance rates. |

| Healthcare and Insurance providers

Schools, clinics, hospitals, and other sites of screenings/educational sessions |

They will work to make sure the intervention is able to be implemented through funding and resources such as personnel. Healthcare and insurance providers will work together to make screenings more affordable and accessible to people. Schools, clinics, hospitals and other sites will be where the screenings as well as the educational/informational sessions will be held. | What is the cost benefit of the program? How will our profits be affected by the program? How long will our venues be used? How effective are the informational/educational workshops/sessions? How large is the participation in these programs? How effective are these workshops? How sustainable is this program? | If the program effectively increases breast cancer attendance screening rates in a cost effective, timely manner, the schools and other venues will continue allow program sessions to be hosted there. The healthcare and insurance providers will continue to support the program. | The healthcare and insurance providers will not continue to support the program if the intervention is not sustainable and effective. If the program does not prove effective in increasing breast cancer screening attendance rates, some venues such as the schools may refuse to host educational/informational workshops in the future. |

- Provide the outcome evaluation design(s) name and the scientific notation (Xs and Os). Name the major threats to internal validity for your evaluation, briefly describe why they are a threat, and discuss how your study design or other methods (e.g., incentives) will attenuate these threats. (20 points)

The evaluation design is a randomized experiment. Each of the clinics /hospitals chosen from within the region will randomly assigned to either receive the intervention or the control, which is usual care.

R O1 X O2 O3 (intervention group)

R O1 O2 O3(control group)

The women patients and health professionals randomly assigned to the intervention group will receive a survey and knowledge test prior to the intervention. Next, they will undergo the intervention which will include training/workshops, educational sessions, and text message/reminders. Once the 20 weeks of trainings and educational sessions are over, they will be provided the same knowledge test and survey. The post test will be repeated another time months after the intervention. The control group will receive their usual care. Internal validity is whether or not there is a causal relationship between the two variables being observed. In this case, the variables are the intervention and breast cancer screening rates. The first major threat to the internal validity is a geographic location as although these clinics are all located in the same region, there may be differences in infrastructure that may affect the results. Randomization helps decrease this bias however. There may also be some attrition bias as some people may drop out over time and stop going to the educational sessions. In order to decrease this bias, the sessions will be located in the same places over time. Another way to combat this bias will be to make the screenings and the educational sessions more accessible through more availability of transportation. There may also be some testing bias created by administering a pre-test and then two post-tests; however, the post-tests will each be re-worded to avoid better results caused by repetition. In addition, the brochures/flyers the intervention groups will receive will detail the many benefits/incentives of attending the screenings.

- You are putting together a survey to answer these outcome evaluation questions. Use the table to describe the variables you will measure and how. Be sure to include information on the validity and reliability of the instruments. You may see reliability reported as test-retest reliability or internal consistency (AKA: Cronbach’s alpha). Validity may be reported as face or content validity or construct validity (e.g., factor loadings). (20 points)

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| For example, the theoretical constructs from your model in Figure 1, your health behavior of interest | ||||

| Perceived Barriers & Perceived Benefits

_____________ Perceived Susceptibility & Perceived Severity & Cue to Action

_____________ Self Efficacy |

A Questionnaire by Amy Hoke VanZee mentioned in her paper, “Perceived Benefits and Barriers and Mammography Screening Compliance in Women Age 40 and Older”

_____________ A survey in Kirsten M. Frankenfield’s theses paper, “Health Belief Model of Breast Cancer Screening for Female College Students”

_____________ A survey from the same paper by Kirsten M. Frankenfield mentioned above.

|

The questionnaire takes down demographic information and also asks patients about the perceived benefits and barriers to breast cancer screening.

_____________ The survey records information about the perceived susceptibility and perceived severity of breast cancer from college students among other information such as perceived barriers and benefits to screenings and cue to action.

_____________ The survey records information from female college students on their self efficacy regarding obtaining a mammogram. |

Answer the following with either Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, or Strongly Agree: “Having a mammogram or x-ray of the breasts will help me find lumps early,” “Having a mammogram or x-ray of the breasts would cost too much money,” “Having a mammogram or x-ray of the breasts would be embarrassing,” “Having a mammogram or x- ray of the breasts will decrease my chances of dying from breast cancer.”

_____________ Answer the following with either Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, or Strongly Agree: “My physical health makes it more likely that I will get breast cancer,” “Within the next year I will get breast cancer,” “Breast cancer would endanger my significant relationship,” “Breast cancer is a hopeless disease.” _____________ Answer the following with either Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, or Strongly Agree: “I know how to perform a breast self-exam,” “I have performed a breast self-exam in the past month,” “I know how to get a breast exam performed by a physician,” “I have had a breast exam performed by a physician in the past 3 years.”

|

Reliability: According to the paper by Amy Hoke VanZee, the barriers to mammography scale received a Cronbach alpha score of 0.74 and the reliability coefficient for the benefits to the mammography scale received a Cronbach alpha score of 0.76.

_________________ Frankenfield used the scales of another paper and found that the test reliabilities ranged from .59 to .72.

_________________ The paper used an instrument for self efficacy measurement developed by other authors that measured confidence in getting a breast exam. It was found that the instrument had construct validity and a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.87. |

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

- Provide the following data collection forms for monitoring the program process. More than one form may be submitted for a given category, but all forms must be clearly labeled. (18 points)

- Recruitment and enrollment – how will you track who you invite to participate in your intervention and who actually takes part? The first way that we will track who we invite to participate in the intervention vs who actually takes part is to administer a form to the clinics/hospitals included in the intervention. The enrollment forms will be attached to the recruitment letters.

A. This will be the recruitment letter given to the clinics/hospitals/schools within the region.

Dear _____________,

The University of Georgia School of Public Health, in partnership with students in Health Promotion, would like to invite you and your facility to participate in our intervention/study about breast cancer screening attendance rates. We are taking a holistic approach to try to increase breast cancer screening attendance rates in order to decrease the rates of breast cancer mortality in this community in the long term. Your participation would be completely voluntary. If you are interested in partnering with us, please fill out the enrollment form attached to this letter and submit it to {insert mailing address here} or email it to us online at {insert email}. If you have any additional questions regarding the details of the intervention, please do not hesitate to reach out to us at {insert email} or call us at {insert phone number}. Please consider participating in this important study. Thank you for your time.

Sincerely,

{Health Promotion Students}

University of Georgia School of Public Health

B. This will be the recruitment letter given to potential participants/health professionals of the intervention.

Dear Dr./Ms./Mr.,

The University of Georgia School of Public Health, in partnership with students in Health Promotion, would like to invite you to participate in our intervention/study about breast cancer screening attendance rates. We are taking a holistic approach to try to increase breast cancer screening attendance rates in order to decrease the rates of breast cancer mortality in this community in the long term. Your participation would be completely voluntary and you would be able to withdraw from the study at any time you please. Your participation would consist of attending weekly educational sessions/workshops for 20 weeks as well as taking knowledge tests and a survey about facets of breast cancer screening. If you are interested in participating in this study, please fill out the enrollment form attached to this letter and submit it to {insert names of clinics participating} or email it to us online at {insert email}. If you have any additional questions regarding the details of the intervention, please do not hesitate to reach out to us at {insert email} or call us at {insert phone number}. Please consider registering for this important study. Thank you for your time.

Sincerely,

{Health Promotion Students}

University of Georgia School of Public Health

C. This form will be provided to each clinic/hospital/school at the beginning of the intervention as an enrollment form.

Clinic/Hospital/School Name:___________________________________________________________________

County:____________________________________

Date:_________________________

Hosting? (Screenings/educational workshops/informational sessions)______________________________________

Contact Phone Number:_______________________

Contact Email:_________________________________

Number of Health Professionals Participating:________________________________________________

How were participants invited to the intervention?_______________________________________________________

How many participants enrolled?_____________

How many participants refused?_____________

What were reasons for why they refused?_____________________________________________________________

D. This is the enrollment form for the participants of the intervention.

Name:__________________

Date enrolled:_______________

Date of Birth:_________________

Phone Number:_______________________

Email:__________________________________________

Home Address:_______________________________________________________________________________

Clinic/Hospital/School Name:_____________________________________________________________________

Clinic/Hospital/School Address:___________________________________________________________________

E. This is a form about the recruitment/enrollment of clinics/hospitals/schools.

Name of Person Filling out Form:________________________

How many clinics/hospitals/schools were invited to participate in the intervention?____________

How many accepted?___________

What were reasons given by clinics/hospitals/schools for why they didn’t participate?_________________________________

2. Attrition – how will you know if participants complete all of the observations (O’s from your study design) and all of the intervention components (from your Outputs column of your logic model)? Attrition will be recorded by recording the amount of surveys/knowledge tests given to patients and comparing it to the amount of completed surveys/knowledge tests we have at the pretest and at each of the two post tests. In addition, attendance will be taken and recorded at each of the educational sessions.

A. This form will be given to each clinic/hospital to fill out at the pretest and at both of the post tests.

Date:_____________________

Number of Initial Participants:___________

Current Number of Participants:___________

| Attendance Form | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Participant Name | Weeks | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

B. This form will be given to each participant at the beginning of the intervention.

Name:__________________

Age:___________

Date:_______________

Date of Birth:_________________

Phone Number:_______________________

Email:__________________________________________

Home Address:_______________________________________________________________________________

Do you plan on attending the educational sessions and workshops that will be provided? Why? ____________________

C. At each of the post tests, form B and this form (form C) will be provided to the participants of the intervention group.

Approximately how many educational sessions did you attend?_____________________

What was your reason for attending the sessions?_____________________________________________________

If you did not attend any of the sessions, why?_______________________________________________________

If you stopped attending the sessions, why?_________________________________________________________

3. Fidelity of the program – how will you know if the intervention was implemented as you had planned? This should match your Outputs column of your logic model. I will know if the intervention was implemented as planned if the amount of workers, brochures/flyers, and the amount of educational sessions match the outputs column of the logic model (At least 100 workers involved, 5,000 brochures/flyers handed out, and 20 educational sessions (at least 5 of those being workshops)).

A. This form will be filled out by each clinic/hospital performing in the intervention at the end of the second post test.

How many brochures were passed out?_____________

If less than the goal amount of brochures/flyers were passed out, please explain why._____________________________________

How many educational sessions/workshops were held at your facility? And what did they cover?_____________

Were all of the educational sessions/workshops that were scheduled occur? If not, why not?________________________________

How many of your workers were involved with the intervention?______________

What were some reasons why workers did not want to participate in the intervention?____________________________________

Was the curriculum for the educational sessions/workshops clear? Why or Why not? _____________________________________

How high was average attendance at each of the educational sessions/workshops? (Very High, High, Half, Low, or Very Low)_______________________

How engaged were the participants of the intervention? (High, Medium, or Low)_________________________

What were some reasons given by the staff and the participants to explain why engagement was high/medium/low?_______________________________________________________________________________________________

What percentage of participants with scheduled breast cancer screening appointments were sent reminder text messages/letters?________________

Did any participants or professionals mention seeing breast cancer screening in some form on local news?

References

American Cancer Society (2014). Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf.

Baker, D. W., Brown, T., Buchanan, D. R., Weil, J., Balsley K., Ranalli, L., …Wolf, M. S. (2014). Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 174(8):1235–1241. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2352.

Breast Cancer Rates by State. (2014, August 26). Retrieved June 04, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/state.htm

Frankenfield, Kirsten M., “Health Belief Model of Breast Cancer Screening for Female College Students” (2009). Master’s Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. Paper 258.

Hoke VanZee, Amy, “Perceived Benefits and Barriers and Mammography Screening Compliance in Women Age 40 and Older” (1998). Masters Theses. Paper 370.

Kerrison, R. S., Shukla, H., Cunningham, D., Oyebode, O., & Friedman, E. (2015). Text-message reminders increase uptake of routine breast screening appointments: a randomised controlled trial in a hard-to-reach population.British Journal of Cancer, 112(6), 1005–1010. http://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.36

MacLaughlin, K. L., Swanson, K. M., Naessens, J. M., Angstman, K. B. and Chaudhry, R. (2014), Cervical cancer screening: a prospective cohort study of the effects of historical patient compliance and a population-based informatics prompted reminder on screening rates. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 20: 136–143. doi: 10.1111/jep.12098