Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Naumann et al. (2015) | Since 2008, all motorcyclists in North Carolina have been required to wear a helmet when operating their vehicles. This study is one of the first analyses of the effects of this state law. Hospital admissions for motorcyclists with traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and associated injuries were obtained for 2011, and compared with estimated admissions rates if NC had not enacted the helmet law. Economic effects were also estimated. | The study population included all motorcyclists admitted to hospitals with TBIs as the result of a motorcycle crash in the state of North Carolina (n=275). The control population included the estimated number of motorcyclists that would have been admitted to hospitals with TBIs as the result of a motorcycle crash in North Carolina had the state’s helmet law not been implemented (n≈465-501). | The measurements used were number of motorcyclists with TBIs and the estimated medical charges under the helmet law and a hypothetical non-helmet law situation. | Implementation of a helmet law in North Carolina prevented roughly 190-226 admissions of motorcyclists with TBIs. The law also prevented between $25.3 million and $31.0 million in hospital charges.

No test statistics were provided. |

Technically, there was no follow-up time in this study because no time passed between the two measurements. All data was taken from the entire year of 2011. |

| Usha et al. (2013) | Kerala, India implemented a mandatory motorcycle helmet law in 2007. To display the effectiveness of this law in preventing injury amongst motorcyclists, researchers obtained data from people that sustained facial injuries in nonfatal motorcycle accidents at one emergency department for the six months following enactment of the helmet law. | Patients included in this study were those that reported to the Emergency Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Government Dental College in Calicut after sustaining facial injuries in a nonfatal motorcycle accident during the six months following the enactment of the helmet law (n=191). A control group was used, and it included the same type of people in a six month period two years prior to enactment of the helmet law (n=289). | The most important variables in this study were percentage of patients using helmets at the time of their accidents both pre- and post-law, and amount/type of injuries in helmeted and non-helmeted individuals. | Helmet usage increased by 32% in the six months after Kerala enacted the helmet law.

Incidence of facial fractures:

|

Follow-up time included the 6 months following enactment of the mandatory motorcycle helmet law – data was collected as patients presented to the hospital throughout that period of time. |

| Olsen et al. (2016) | Less than have of states in the US have universal helmet laws- just as many have partial helmet laws, where only certain members of the population (typically restricted by age) are required to wear helmets when operating a motorcycle. This study used data from 11 states (five with universal helmet laws and six with partial helmet laws) to determine the effectiveness of both types of helmet laws on helmet usage, number of injuries resulting from motorcycle crashes, and medical charges resulting from these motorcycle crash-related injuries. | This study included motorcycle crashes in the 11 states (n=73,759).

28,207 of these crashes were from partial law states, and the other 45,552 were from universal law states. |

Variables included helmet use rates (one subcategory here included use rates in those under 21), emergency department and inpatient charges, fatality rates, and the rates of three types of injuries: head injuries, facial injuries, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). | Helmet Use (General): Partial states: 42% Universal states: 88%Helmet Use (Under 21): Partial states: 44% Universal states: 81%There were significantly less head, facial, and traumatic brain injuries in universal law states than partial law states [p-values all <0.01]. Mean and median hospital charges were lower in universal law states than partial law states [p<0.01]. |

There were no specific follow-up points, as data was collected continuously from 2005-2008. |

In 2013, the Community Preventative Services Task Force recommended universal motorcycle helmet laws after a systematic review of the evidence available at that time. Universal helmet laws are explicitly recommended over both partial helmet laws and no helmet laws. In the time that has passed since this recommendation, there has been sufficient evidence to instead strongly recommend universal helmet laws as a strategy that increases helmet usage, thus lowering injuries and fatalities among motorcyclists.

The new studies that were reviewed provided data from multiple states in the United States and one state in India. Though the findings were not exactly novel, this data indicated that the implementation of universal helmet laws increases helmet use rates amongst motorcyclists, lowers injury rates in crashes, and decreases the financial burden that results from crash injuries. This not only applies to implementation in states with no existing helmet laws, but also states with existing partial helmet laws. These partial laws typically only require motorcyclists under the age of 18, 19, or 21 to wear helmets, and currently exist in 28 states (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 2016). As is evidenced in studies from 2013 onwards and previous studies that were involved in CPSTF’s 2013 recommendation, partial helmet laws do not adequately encourage helmet usage and thus result in unnecessary injuries, fatalities, and costs amongst motorcyclists. In 2012, Michigan repealed its universal helmet law in favor of a partial helmet law. After this repeal, rates of helmet non-usage among motorcyclists increased from 7% to 29%. This resulted in increased crash fatalities, longer hospital stays, and increased medical costs for injuries (Chapman et al. 2014). Though this article was not included in the above review because it was not a study of the implementation strategy but rather a review of a repeal of this strategy, it very clearly demonstrates how subpar helmet laws do not provide enough protection for motorcyclists.

There is little to no evidence that opposes the implementation of universal helmet laws. Now that it is very clearly known that universal laws are more protective than partial laws, and that repealing universal laws in favor of partial laws results in more fatalities and injuries amongst motorcyclists, it should be strongly recommended that universal helmet laws are implemented nationwide

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is used to explain why people participate (or do not participate) in preventative measures against harm. The model intends to motivate practices involved in good health and address the reasons why people might not follow these practices. In this model, six main constructs are thought to influence people’s behaviors: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cue to action, and self-efficacy (NCI, 2005). Though the intervention here is creating a universal motorcycle helmet law, these constructs must also be addressed in order to achieve a high rate of helmet usage.

Constructs Used in Motorcycle Helmet Promotion

- Perceived susceptibility:

- Individuals must believe that it is reasonably likely that they would be susceptible to injury or other consequences if they do not wear helmets when operating a motorcycle. A 2004 study of motorcycle helmet use in adolescents in Italy found that adolescents who had not previously been in an accident while riding a motorcycle were less likely to wear helmets regularly (Bianco et al., 2005)- suggesting an “it won’t happen to me” attitude towards motorcycle crashes. Adolescent and adult riders alike need to be adequately educated on the frequency of motorcycle crashes and subsequent injuries, perhaps in mandatory helmet education programs that can be implemented into the process of obtaining a license to operate a motorcycle.

- Perceived severity:

- Individuals must believe that the consequences of not wearing a helmet when riding a motorcycle can be severe. This construct goes hand-in-hand with perceived susceptibility, and both should be used together as key points in a helmet education program. Without delving into scare tactics, riders need to be aware of the physical and financial consequences of not wearing a helmet, especially in the event of a crash. As mentioned in the three main studies above, non-helmeted riders tend to experience more severe injuries and more financial burden after a motorcycle crash. Additionally, under a universal helmet law, riders that are non-compliant would face consequences such as monetary fines or license suspensions.

- Perceived benefits:

- Individuals must believe that there is a benefit to taking action and wearing a helmet when operating a motorcycle. This construct also ties in closely with the previous two because it details the positive effects of wearing a helmet rather than the negative effects of not wearing a helmet.

- Perceived barriers:

- Individuals must not believe that the material and/or psychological costs of taking action effectively prohibit them from taking action. This construct is seen most obviously in lesser-developed countries, where many people do not wear adequately protective motorcycle helmets simply because they cannot afford them. Additional perceived barriers tend to include lack of access for passengers, attractiveness, restricted field of vision, and discomfort (Dennis et al., 2013); these are likely to be the more frequently perceived barriers in more developed countries where helmet affordability is less of an issue.

- Cues to action:

- Individuals need cues to action in order to change their behavior. These cues can include a universal helmet law, active and effective enforcement of the law, mandatory education programs, public service announcements on radio or television, better designed helmets, etc.

- Self-efficacy:

- Individuals must be confident in their ability to successfully don a helmet and take action in their own safety. For this construct to be fulfilled, riders must know how to properly wear a helmet (and they must feel confident that they are doing it correctly). Riders can also encourage fellow riders to wear helmets, providing verbal reinforcements to their peers.

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

While Florida had a universal motorcycle helmet law at one time, it was repealed in July 2000 in favor of a partial helmet law (Muller, 2004). This partial law exempts anyone that is at least 21 years of age from wearing a motorcycle helmet, provided that they have at least $10,000 in health insurance. Though this law is not starkly different from various other partial laws across the United States, Florida in particular was selected for its alarming rate of motorcyclist death. 456 people on motorcycles were killed in 2012, accounting for nearly 10% of all motorcyclist deaths across all fifty states (despite Florida’s motorcycle registration only accounting for 6-7% of total motorcycles in the United States). Over half of these riders were not wearing helmets (NHTSA, 2014). The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that around 37% of non-helmeted riders killed in crashes would not have been killed had they been wearing helmets. This translates to roughly 90 lives that could have been saved in Florida in 2012, had the riders simply been wearing a helmet. This disproportionate amount of motorcyclist deaths in Florida is more attributable to the repeal of the helmet law than any other potential modifying factor(s) (Muller, 2004), making Florida one of the best possible candidates for re-implementation of a universal helmet law.

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Increase the preventative behavior of helmet wearing, implement cues to action | The health behavior model construct of cues to action is the basis for the primary component of this intervention. Cues to action move people to change their behavior, and making helmets a legal requirement when operating a motorcycle would certainly encourage compliance. People will be motivated to wear helmets in order to avoid legal consequences, such as fines or license suspension. | The primary strategy in this intervention will be to implement a universal helmet law in the state of Florida. To do so, a comprehensive legislation will be written and presented to state legislature. This will not be an easy task, as the legislation will need strong governmental support in order to be passed. The legislation will address the definition(s) of compliance (i.e. what types of helmets are/are not acceptable), which agencies will be responsible for enforcing the helmet law, and consequences for non-compliance. In order to gain governmental support, we will present key government role players with current and past data on Florida’s motorcycle crash injury and fatality rates, as well as emphasizing the spike in these rates that occurred following repeal of the old universal helmet law. The benefits of a universal helmet program from both public health and economic standpoints will be stressed, and a reasonable potential timeline for implementation will be presented. |

| Improve self-efficacy, educate people so that their perceived threat and severity of injury is accurate | Mandatory helmet education would tie the two health behavior model concepts of cues to action and self-efficacy together quite nicely. By learning some of the statistics related to motorcycle helmet usage and injuries/fatalities/costs after crashes, riders will have an accurate perceived threat and severity of injury and thus be able to make an educated choice when deciding whether or not to wear a helmet. Further, educating riders on correct helmet usage will instill in them confidence that they know how to adequately protect themselves when operating a motorcycle. | As part of the universal helmet law described above, all motorcyclists will be required to complete a mandatory 1-hour motorcycle safety education program. Though all protective gear will be included in the program, helmets will be its main focus. Riders will be educated on helmet usage and shown statistics similar to those that were presented to legislators. Riders will be shown what specific safety features to look for when choosing a helmet, after which they will receive hands-on instruction concerning how to properly don and adjust a helmet. To make this program easily accessible and enforceable, it will be integrated into the licensing process. To receive a license to operate a motorcycle, one must complete this program during their licensing appointment. The program must be repeated at each license renewal. |

| Implement sufficient cues to action to encourage behavioral change | A mass media campaign is one of the best examples of a cue to action because it is a straightforward way of encouraging people to take a positive health action. This campaign will be visible to motorcyclists and non-motorcyclists alike, making sure that the public is aware that motorcycle helmet usage is a critical public health issue. | The mass media part of this campaign will include television and radio commercials informing viewers and listeners of the new helmet law and of the consequences that can follow non-compliance. Commercials prior to implementation of the law can inform riders that they need to take action before it it implemented, and commercials following implementation of the law can remind riders that they need to be wearing their helmet when riding their motorcycle, lest they face health or legal consequences. The roadside sign campaign will help to remind motorcyclists on the road that helmet usage is required by law. Roadside signs will be placed on major highways throughout Florida, and will be similar to Georgia’s “click it or ticket” signs that remind drivers that seatbelt usage is required by law there. |

| Reduce perceived barriers to change | Creating a helmet rebate program would address the health behavior model’s construct of perceived barriers to change. Many motorcycle riders, particularly those who choose motorcycles over cars because they are less expensive, may view helmets as an expense that they cannot afford. On Motorcycle-Superstore.com, a popular online motorcycle supply store, most helmets are over $100. Though cheaper options do exist, people may have limited access to these helmets and are forced to choose either an expensive helmet or no helmet at all. | To decrease perceived barriers to change, a helmet rebate program will be implemented in Florida. This program is similar to a program implemented years ago in Victoria, Australia that provided rebates on bicycle helmets to encourage helmet use (McDermott, 1995). Motorcyclists purchasing new helmets will be eligible for a partial rebate on their helmet after submitting proof of purchase of a helmet that meets all regulations and requirements detailed in the new helmet law. If riders in need of helmets can also provide adequate proof of financial need, they may be eligible for a larger (and potentially full) rebate depending on their level of need. Funding for this rebate program could be provided from revenue that comes from traffic citations and tickets. |

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | X | Long-term Outcomes |

| Funding to enact universal helmet law, legislators willing to pursue passage of the law, funding for development of educational program, personnel to administer educational program, classrooms to hold educational sessions, funding to implement mass media campaign (which will include billboards, roadside signs, television commercials, and radio commercials), funding for helmet rebate program | Implementation of universal helmet law that will require all motorcyclists in Florida to wear an approved helmet when operating a motorcycle.

Mandatory educational sessions that will involve teaching motorcyclists the risks of not wearing a helmet, the benefits of wearing a helmet, and how to properly wear a helmet. Mass media campaign that includes roadside signs, television commercials, and radio commercials. Prior to implementation of the law, these signs/commercials will inform riders of the new law and the date on which it will take effect. After implementation of the law, these signs/commercials will remind riders that they are legally required to wear a helmet and that they will face serious safety and legal consequences if they do not comply. A helmet rebate program will be implemented to help with those who may have trouble affording an approved helmet. Participants must provide proof of financial hardship and rebates will be provided on a sliding scale so that participants will pay only what they can afford for their helmet. |

~560,000 educational sessions (one for each registered motorcyclist in Florida); ~1,000 roadside signs throughout Florida roadways; 67 DMV workers trained to administer education program (one per county) | Change attitudes towards helmet wearing, increase the preventative behavior of helmet wearing, educate people so that their perceived threat and severity of injury is accurate, improve self-efficacy, implement sufficient cues to action | column removed as per recommendation | Decreased mortality rates from motorcycle crashes, decreased injury rates and severity from motorcycle crashes, decreased spending on hospital bills/legal fees related to motorcycle crashes

|

Intervention hypotheses:

Implementation of a universal helmet law will result in increased rates of helmet usage in Florida.

Helmet education will improve self-efficacy amongst motorcycle riders, along with improving motorcyclists’ attitudes towards helmets, thus making them more inclined to wear them. Helmet education will make sure riders have an accurate perceived sense of threat and severity of injury. Helmet education will also increase proper helmet use by making sure motorcyclists know how to correctly put on and adjust their helmets.

Television and radio commercials will increase helmet usage prior to law implementation by telling riders of the law, and after implementation by continuing to remind motorcyclists of their importance (from both legal and safety standpoints).

Roadside signs will increase helmet usage by reminding riders on the road that they risk being ticketed for non-compliance.

Implementing a helmet rebate program will increase helmet usage among poorer groups of motorcyclists.

Causal hypotheses:

Increased rates of helmet usage that result from the universal helmet law, education, mass-media campaigns, and the rebate program will lead to decreased mortality and injury rates, decreased injury severity, and less financial burdens following motorcycle crashes.

Goal: Increase rates of observed helmet usage amongst motorcyclists.

Objective: Despite the majority of motorcyclists reporting that they wear helmets, observed helmet usage in Florida is less than 50% (Turner, Hagelin, Chu, 2004). Prior to repeal of Florida’s helmet law, observed helmet usage was close to 100%, so one year after re-implementation, we would like to see observed helmet usage rates of at least 95%.

Goal: Improve attitudes towards wearing helmets amongst motorcyclists.

Objective: Roughly 68% of motorcyclists in Florida believe they should be required to wear helmets (AAA, 2016). One year after implementation, we would like to see this increase to at least 78%.

Goal: Improve self-efficacy and knowledge amongst motorcyclists.

Objective: Pre-implementation data for this goal was challenging to find, but ideally, we would like to have at least 90% of motorcyclists feel confident in their knowledge of helmet usage, be confident that they can afford an approved helmet, and have a realistic grasp on the benefits of wearing helmets in terms of lives saved and injuries prevented. After implementation, this can be quantified by a brief quiz/survey that follows the mandatory education program. Since Florida motorcyclists must renew their license every 4-6 years, depending on the type of license they hold (DMV, n.d.), it is reasonable to expect the majority of Florida motorcyclists to have renewed their license and thus participated in the educational program 5 years following implementation. Thus, we will ideally see at least 90% of motorcyclists feel confident in the above tasks within 5 years of implementation.

Goal: Implement sufficient cues to action.

Objective: Again, no data was found addressing this goal. However, post-implementation, the effectiveness and overall reach of the mass media campaign can be evaluated by a survey of Florida motorcyclists. Ideally, we would like 100% of motorcyclists to have seen or heard a television/radio ad or roadside signs between the weeks prior to law implementation and the year following it. (Further questions to evaluate the effectiveness of the campaign could include questions similar to these: Did you know about the universal helmet law prior to its implementation? Where did you first hear about it? Check all of the following ads/announcements/signs that you have seen.) We would also like to see a majority (>50%) of riders stating that the campaign did encourage them to wear a helmet.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Motorcyclists | Subjects of intervention | What type of helmet do I need to wear? Will a helmet actually increase my safety? What are the legal penalties if I am caught not wearing a helmet? | Decreased risk of injury or death and less financial burden as a result of a motorcycle crash, increased trust in helmet-wearing as a preventative safety behavior, decreased traffic citations | Continued high risk of injury, death, and increased costs after a motorcycle crash, stable or increased traffic citations |

| National Highway Traffic Safety Administration | Creators of mass-media campaign and education program | How many signs/commercials are enough to be effective? What is the cost? What are the most effective placements or timings of ads/signs? What are the most effective things to present in ads? How long should the ad campaign continue? How will we know if the ad campaign and signs are effective? | Insight for future ad campaigns, data on effectiveness of different types of signs/ads, potential investors into future campaigns | Financial loss, decreased chance of implementing similar ad campaigns in the future, insight for how to improve future ad campaigns |

| Healthcare organizations and consumers | Involved in costs associated with motorcycle crash-related injuries | How will my costs change as a result of the new helmet law? | Decreased costs, decreased length of care in hospitals | Stable or increased costs, stable or increased length of care in hospitals |

| Legislators | Creators and implementors of law | Will my constituents support me/this law? Will the law be too challenging to implement? What is the timeframe from drafting a legislation to getting it passed and implementing it? | Gain of support from certain constituents, gained expertise on helmet laws for implementation in other states, boost reputation | Loss of support from certain constituents, hurt reputation, insight for how to improve future legislation |

Study Design for Outcome Evaluation

A one-group quasi-experimental study design will be used to evaluate the outcome of the law implementation. Since the entire target population is going to be subject to this implementation, pre-intervention data will be used as pre-test “control” data.

O1 X O2 O3

X = treatment (law implementation)

O1 = pre-test helmet usage rate measurement

O2 = 6 months post-test helmet usage rate measurement

O3 = 1 year post-test helmet usage rate measurement

Since this intervention will apply to the entire target population and not a sample subset, no randomization will be necessary. Helmet usage rates will be measured prior to implementation of the helmet law, and again after 6 months and 1 year have passed.

Helmet usage rates will be measured via direct observation in each county in Florida. This will involve posting multiple observers at main roads and highways throughout each county for a period of one week (to account for differences in traffic patterns that occur day-to-day). Each time a motorcyclist is observed, whether or not he or she is wearing a helmet will be recorded. The usage rates for each county will be determined from this data, and a weighted average for the entire state will be calculated based on each county’s number of registered motorcyclists.

This study design will present some threats to internal validity. Firstly, experimental mortality (persons dying or otherwise leaving the observed population throughout the study) will inevitably result in the observed population not being the same after law implementation as it was before. However, the extremely large population size (~560,000) and relatively short follow-up time (6 & 12 months) virtually eliminates any significant impact this will have on results. On an individual basis, a maturation effect could be observed, where people start wearing helmets not because of a legal obligation to do so but rather they “grow out” of reckless behavior. This, along with other confounding variables that could threaten internal validity, can be potentially be accounted for in a follow-up survey of a random sample motorcyclists. Motorcyclists could be asked if they started wearing a helmet regularly after not having previously done so, and asked to list the reason(s) for that behavioral change. This may help determine approximately what percentage motorcyclists who began wearing helmets did so due to the law implementation.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Increased rates of helmet usage | Direct observation (Streff et al., 1993) | Subjects were directly observed in order to determine whether or not they were wearing a motorcycle helmet | This will be a simple yes/no- is the observed motorcycle rider wearing a helmet? | Inter-observer reliability of at least 85% for each set of observers |

| Improved attitudes towards helmet wearing | SMTSL questionnaire to measure attitudes (Tuan et al., 2005) | Questionnaires were administered and measured attitudes towards a behavior and compared them with motivation to perform that behavior | On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being strongly disagree, and 5 being strongly agree, how do you feel about the following statements?

|

Cronbach alpha reliability ranged from 0.7 to 0.87 and was found to be generally satsifactory.

Motivation to learn/change has moderate correlation with positive attitudes towards the goal behavior (r=0.41). |

| Improved self-efficacy and knowledge | General self-efficacy scale (Schwarzer et al., 1997) | Scale used to measure anticipated difficulty in behavioral change, rate confidence levels in learned behaviors and facts | Select yes or no to indicate whether or not you agree with the following statements:

|

Obtained correlations of self-efficacy with outcome behaviors were moderate and significant.

Internal consistencies ranged between α = 0.75 and 0.90, indicating reliability and discriminant validity. |

| Implement sufficient cues to action | Questionnaire and scale about effectiveness of cues to action (Gallo, Staskin, 1997) | Survey included questions about whether and how often cues to action were seen, what prompted subject to perform target behaviors, how often did subjects perform target behavior

5-point Lickert scale was also used to rank effectiveness of cues to action |

In the past 12 months, have you seen any signs or advertisements encouraging you to wear a motorcycle helmet? If so, was it a roadside sign, television commercial, radio commercial, or other?

On a scale of 1-5 with 1 being not effective at all and 5 being very effective, how would you rank the signs or advertisements that you saw in encouraging you to wear a motorcycle helmet?

|

Overall reliability coefficient = 0.90 (ranged from 0.85 to 0.98)

Content validity = 100%

|

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

- Provide the following data collection forms for monitoring the program process. More than one form may be submitted for a given category, but all forms must be clearly labeled. (18 points)

- Recruitment and enrollment – how will you track who you invite to participate in your intervention and who actually takes part?

- Attrition – how will you know if participants complete all of the observations (O’s from your study design) and all of the intervention components (from your Outputs column of your logic model)?

- Fidelity of the program – how will you know if the intervention was implemented as you had planned? This should match your Outputs column of your logic model.

Recruitment and Enrollment

For much of this intervention, recruitment and enrollment is unnecessary because data will be taken either from direct observation or from the brief survey/questionnaire that follows the mandatory education program. The survey will not be optional, because this would likely encourage participants to skip it due to convenience, but participants will be informed that results of the survey will be kept anonymous and they will have the option to give or deny consent for their results to be used.

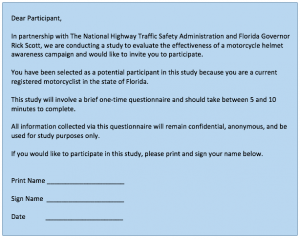

For the other parts of this intervention, especially where evaluation of the mass media campaign is concerned, potential participants will receive an enrollment form prior to completing the relevant survey/questionnaire. This form and the survey that follows will be offered to every motorcyclist that renews his or her registration during a one-month period that occurs one year after implementation of the mass media campaign. The form is as follows:

Records of who does/does not participate in the survey will be kept in a database, but will remain confidential and only be utilized for bookkeeping purposes, as there is no follow-up requirement for the study.

Attrition

For the purposes of this study, follow-up with participants will not be necessary. The data collected will not require follow-up data collections, since it will be compared to pre-intervention data.

Fidelity of the Program

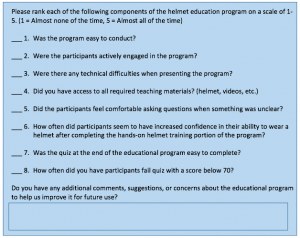

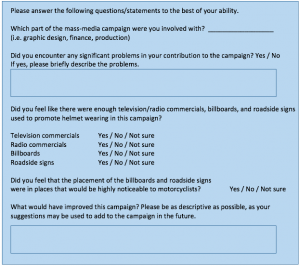

The program’s fidelity will be assessed in multiple ways. Surveys will be presented to the DMV staff members that conduct the mandatory educational program to assess its perceived effectiveness and ease of implementation. Surveys will also be presented to those involved with creating and distributing elements of the mass-media campaign to assess similar characteristics. The two surveys are as follows:

In order to ensure that the content of the educational program meets the established standards, educators will also be asked to provide an outline of the course that they teach. If variations are observed, educators can be re-trained so that the course they are providing meets standards for all participants.

REFERENCES:

McDermott, F. T. (1995). Bicyclist head injury prevention by helmets and mandatory wearing legislation in Victoria, Australia. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 77, 38-44. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

Schwarzer, R., Bäßler, J., Kwiatek, P., Schröder, K., & Zhang, J. X. (1997). The Assessment of Optimistic Self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese Versions of the General Self-efficacy Scale. Applied Psychology,46(1), 69-88. Retrieved June 2, 2016.