Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

Table 1. Literature Review

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Stubbs et al., 2014 | HPV vaccinations were offered to girls who attended specific middle schools in Guilford County that had temporary school located clinics which provided the vaccinations free of charge. Schools that hosted these clinics were referred to as ‘host schools’, while schools that did not host them were referred to as ‘satellite schools’. Host schools had four one-day clinics and offered different doses of the vaccine (one, two, and three dose). Students who attended ‘satellite schools’ could get the HPV vaccine from a ‘host school’ if they wanted to and for the study was the comparison group. Students from both types of schools were provided with information and consent forms and had to have a parent with them in order to receive the vaccine in addition to their signed consent forms. | The intervention was offered to middle school girls and in Guilford County (N=7916). There was a total of six host schools and fifteen satellite schools with the majority of schools being urban schools (67%). The median age of girls to receive the HPV vaccination was 12 years and the median grade level was the seventh grade. A total of 171 middle schools girls were given the vaccine. | The main outcome of interest for this study was the total number of girls to receive at least one dose of HPV vaccine. In addition to this, they also wanted to know how many girls received all three doses of HPV and also wanted to see if there was a difference among vaccinations between host and satellite schools. | Of the 171 middle school girls who got vaccinated they received; one dose (n=12), two doses(n=22), three doses(n=137). Higher vaccination rates were seen in girls who attended host schools than girls who attended satellite schools. (OR=6.56, 95% CI= 3.99-10.78). |

8 months

October 2009-June 2010 |

| King et al., 2006 | Influenza vaccinations were offered in elementary schools in Maryland, Texas, Minnesota and Washington state. Schools were grouped into clusters based on geographic, ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics. From each cluster one school was chosen as the intervention school where the live attenuated influenza vaccine was provided and the rest of the schools in the cluster were control schools. Children who were 5 years or older were offered the influenza vaccine intranasally with parents consent. | Eleven clusters were identified for this study. A total of 28 schools participated in the study; intervention schools (n=11) and controls schools (n=17). The total student population was greater in control schools (n=9451) than intervention schools (n=5840). The ethnic distribution among both intervention and control schools was very similar with the majority of students being white; intervention=70% and control=71%. The average age of children who received the vaccination was 7.9 years. | The objective of the study was to see the effect school-based vaccination programs had on the households of school attending children. Influenza-like symptoms, medications, hospital visits and leave of work were all measured before and after vaccination was given. The study also wanted to assess the number of days students missed school and also looked at school attendance. | 2,717 students out of 5,840 students received the influenza vaccination. Children and adults who were in control schools reported more influenza symptoms and received more outpatient care than children and adults in intervention schools (p<0.001) Children and adults in intervention schools reported using less medications than children and adults in control schools (p<0.0001) More absences were reported among children who attended control schools (6.63/100) than children in intervention schools (4.34/100). |

Seven days after vaccination was provided, participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire that included questions about medications, medical visits, and symptoms. |

| Daley et al., 2013 | A group randomized study was conducted among Denver public schools where vaccination clinics were held for students who were in 6th to 8th grade. Schools were divided into interventions schools where the clinics were held and control group where they did not hold vaccinations clinics All the vaccines that are recommended for adolescents were available at the clinic. | There was a total of 7 intervention schools and 7 control groups. The median percent of student body being a racial/ethnic minority was greater in the intervention group (n=82) than in the control group (n=65). The median number of enrolled students was greater in the control group (n=350) than in the intervention group (n=289). In the intervention schools, there was a student body of 3,144 students. | The objective of the study was to see how much a school-located vaccination program would costs and see how much of the costs would be reimbursed from health care providers. The study also assessed how the intervention affected vaccination rates.Vaccine administration costs, reimbursement costs, and vaccination outcomes were measured. | 466 students out of 3,144 students received vaccines. The influenza vaccine was administered the most (n=403) and measles-mumps-rubella was administered was least (n=18). $23.98 was the estimated cost to administer one vaccine. Percent of total costs reimbursed which combined vaccine purchase and administration costs was lower among those who had private insurance (56%) and higher in those who had SCHIP insurance (79%). Students in intervention schools were more likely to receive vaccinations (Tdap, HPV, MC4 ) than students in control schools. Ex. intervention vs. control in sixth graders (RR=1.30, 95% CI= 1.08, 1.57) Intervention vs. control in seventh and eighth graders (RR=1.88, 95% CI=1.21, 2.92). |

2 years

2009-randomization 2009-2010-pilot study 2010-2011 academic year-actual study reimbursement data was collected 120 days after last clinic *study did not indicate when clinics were held and when parents were informed of program |

After reviewing three studies about vaccination programs in schools and children care centers, the recommendation for vaccination programs in schools remains as ‘recommended’, however there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for vaccination programs in child care centers. The previous recommendations were based on a systematic review that was published in 2000 and in the past sixteen years a lot has changed in regards to vaccination policies and behaviors. There are changes from the previous recommendations set by the Community Preventive Services Task Force.

There are a few reasons why I chose to keep the current intervention strategy as ‘recommend’ rather than update to ‘strongly recommend’. There is evidence to support that vaccination programs lead to higher immunization rates, but there is still not enough evidence in regards to better health outcomes. In one study that assessed influenza vaccination programs in schools, they found children who had received the influenza vaccine were less likely to spread influenza to their household members, less likely to use medications, had fewer hospital visits and were less likely to miss school (King et al., 2006). However in a study that assessed a HPV vaccinations program for middle school girls, there was no follow up period and participants health outcomes were not assessed so there was no way of knowing how effective the HPV vaccinations were (Stubbs et al., 2014). All three studies found that there were higher rates of immunizations in schools that provided vaccination clinics than schools that did not provide clinics. While having vaccination clinics at schools provides easier access to vaccines, one study found that there are high administrative costs (Daley et al., 2013). They found giving one vaccine can cost up to $22 and reimbursement rates vary depending on the type of insurance plan people have (Daley et al., 2013). Vaccination plans can lead to better health outcomes, but they can be costly so identifying ways to lower these costs can be very beneficial.

From this literature review, there were many studies that were conducted in school settings, but none were conducted in child care facilities like day cares. While child care facilities are similar to school settings, one can not assume the interventions applied in school settings will have the same effect. Conducting more studies in child care facilities, and implementing interventions that have been used in schools could show the similarities or differences between the two settings. Until there is enough evidence, recommendations for schools and child care centers should be separated.

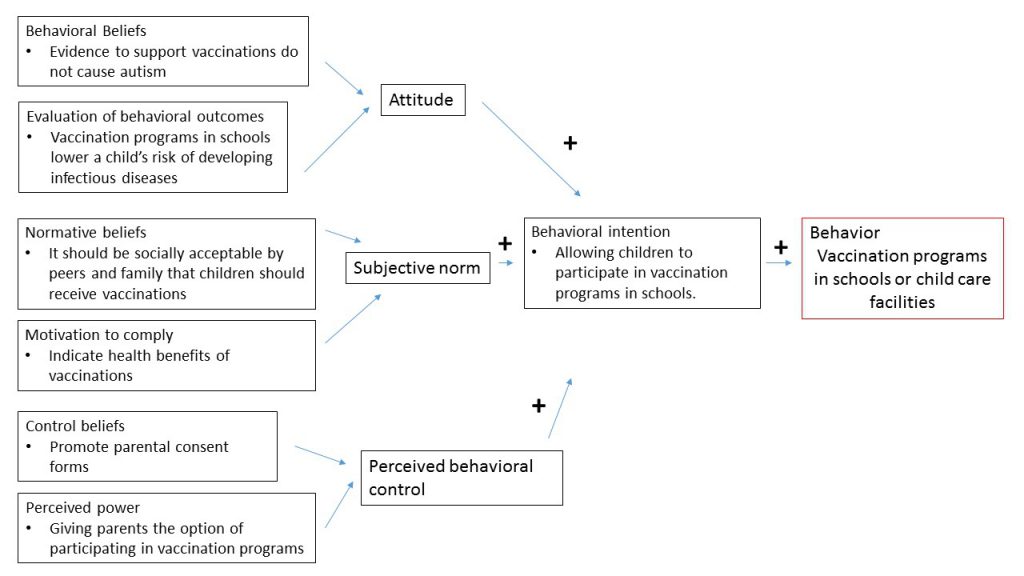

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

In recent years, American society’s beliefs about vaccinations have dramatically changed. For many people, they have started to believe vaccinations cause autism. This can attributed to the high prevalence of autism among young children. With anti-vaccination beliefs on the rise, getting people, especially parents of young children, to change their beliefs is really important. One way of doing so is by basing our intervention on a theoretical framework. For this intervention, I will be using the Theory of Planned Behavior which ‘explores the relationship between behavior and beliefs, attitudes and intentions’ through constructs such as behavior intention, attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control (Glanz 2005). Even with strong scientific evidence that supports how autism is not linked to autism, people’s behaviors and opinions have been changed due to influences by the media and their surrounding social environment. Changing parent’s behaviors on vaccinations can increase immunization rates and lower their risk of diseases. Emphasizing how beneficial vaccinations and showing how they are not the cause of autism is necessary. Also informing parents the ramifications of not vaccinating their children, could potentially change their minds as well.

Constructs

- Behavioral intention is defined as a person’s ‘likelihood of performing the intended behavior’ (Glanz 2005). For this intervention strategy, it refers to how likely parents allow their children to receive or participate in vaccinations programs at schools or child care facilities . Finding the differences in why parents allow or do not allow their children to receive vaccinations could help change the intentions of parents that do not allow their child to receive vaccinations. Studies found that children were more likely to receive vaccines if the school offered vaccination clinics than schools that did not (Daley et al., 2013, King et al., 2006, Stubbs et al., 2014). Finding out if reasons such as more access to vaccines or more awareness is leading to higher immunization rates could also influence whether parents allow their children to participate in these programs.

- Attitude is a person’s opinion of the intended behavior.There are many factors that can affect a person’s attitude toward a behavior. For example, parents of children who are autistic or are associated with families with autistic children may be more against vaccinations than a parent to a child who does not have autism. Also people who come from different cultures may view vaccinations as a bad behavior due to their upbringings. Changing parents attitude of vaccinations is an important part of this intervention.

- Subjective norm is the person’s perception of how other people view the intended behavior. For this situation, this can refer to how peers and families view the act of vaccination. Those who have support from them would more likely to allow their children to receive vaccines.

4. Perceived behavioral control is how much control a person has in performing the intended behavior (Glanz 2005). For the studies where vaccination clinics were offered in schools, parents were required to fill out a consent form in order for a child to receive the vaccines (Daley et al., 2013 , Stubbs et al., 2014).. This behavior could make the parent feel in control since they have the option of not allowing their child to receive the vaccine. This in turn could influence their attitude and behavior intention. Giving parents multiple options is a key component in this intervention.

Figure 1. Diagram of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

Target population

For this program, the target population will be parents of school children between the ages of 5 and 17. Many vaccination programs require parental consent in order to receive vaccines and is one of the reasons why children do not receive them. Among this population there will be a number of socioeconomic status, cultural, and educational differences that can influence their beliefs and participation in vaccination programs in schools. An article looking at why parents refused to give their children vaccines found religious reasons, personal beliefs, philosophical and safety concerns as to why they would not vaccinate their child (Mckee et al., 2016). Understanding these differences among the target population can help form an intervention that addresses all of those concerns.

The transmission of diseases in schools can be fast and children at these schools are at extremely high risk of developing and spreading them. School children, especially young children, are less likely to practice habits such as hand washing or covering their mouth when they sneeze or cough which can spread the disease and put their classmates at risk of developing the disease. By having parents who do not vaccinate their children, they put many people at risk of many preventable diseases. One study found children who were under 18 were had a higher attack rates of influenza during a 2009 influenza pandemic (Ridenhour et al., 2011). If these children have been vaccinated, those attacks rates may have been lower.

Program setting

The program setting will be at elementary, middle and high schools and child care facilities where immunization rates are low. Interventions would be implemented in schools in low income neighborhoods where people have limited access to health care. The intervention program will also be implemented in an affluent (private) schools. A study found high income whites were more likely to utilize exemptions when it comes to vaccines (Yang et al, 2016). Seeing if there is a difference between socioeconomic status as well as type of education could help tailor the program.

Table 2. Proposal of Intervention Methods and Strategies

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Changing parents attitudes toward vaccinations to be more positive | ATTITUDE

In the theory of planned behavior, a person’s attitude is one factor that can influence the likelihood of a person conducting an intended behavior. By changing the attitudes of parents who chose not to vaccinate their children, they may be more likely to allow their children to participate in the vaccination programs in schools. |

HEALTH EDUCATION

Information about the vaccination programs will be provided through pamphlets and will be delivered through the mail. Parents will also receive an email/newsletter that will include information about the program as well as multiple links to articles and studies that provide evidence to support the benefits of vaccinations. These materials will take into account people’s different cultural and personal beliefs that supports it benefits. |

| Increasing perceived behavioral control | PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL When it comes a children, parents like to feel they are in control and responsible for their child’s well-being. Making sure a parent feels like they made the decision to vaccinate their child is very important. Emphasizing parental consent could make parents more likely to participate in the vaccination programs. |

HEALTH COMMUNICATION

Offering information sessions where program staff can explain the program and its benefits and and also provides parents with the to ask questions or their address concerns. It could also be possible to hold multiple sessions that address different concerts such as lack of knowledge or anti-vaccination. This would would be associated with health education and pamphlets and information packets can be distributed at these information sessions. |

| Making childhood vaccinations an socially acceptable task | SUBJECTIVE NORM

For many societies, cultures and religions it may socially unacceptable to receive vaccinations. This is the final factor that can influence a person’s behavioral intention. By talking to leaders of specific groups and informing them of how important vaccinating children are, they could deem it as an acceptable ask.

|

HEALTH COMMUNICATION

With their permission, going to churches and temples to promote the benefits of vaccinating children could be beneficial. Also communicating the what programs intentions are and finding out reasons why they are hesitant to vaccinate could help tailor the program for their needs and concerns. |

Table 3. Logic Model

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| Funding could be provided by local state or even federal agencies Interventions would take place at schools (elementary, middle, and high) or child care facilities.To ensure a participant’s privacy, vaccinations would be administered in multiple classrooms.Medical equipment such as syringes, bandages, appropriate waste disposal of used needles, gloves, cleaning supplies would be needed. Program coordinators who would administer information sessions and distribute pamphlets and recruit parents to participate.Volunteers to help at clinics. Nurses or appropriate health administrators to give the vaccines.If possible, have a doctor or PA on site during the clinics. For extra precautions, have EMS on site as well in case of an emergency. |

Educating parents on the benefits of vaccinations and disproving assumptions they my have previously had through educational sessions and providing materials (health education and health communication).

Meeting with leaders of local communities and religious groups to dispel any negative notions they may have on vaccinating children. |

(would have to base this information on the specific school and see what immunization rates are and how many exemptions there are) Estimating about 200 pamphlets4 sessions; two session for general information about program and about vaccinations being offered.One session for parents who have personal or religious constraints where they can talk to health professionals and address their concerns.One makeup session for parents who are unable to attend any of the previous 3 sessions. Pamphlets and information about intervention program will be emailed to all parents that are on file at the schools. Train 20 health outreach workers for each school Number of parental consents |

One of the objectives of this program is to change the attitudes of parents who chose not vaccinate their children to be more positive. Another objective is to persuade the community to view vaccinations as a socially acceptable task/behavior.Final objective will be to make parents feel they had control over vaccinating their children. |

Making sure participants follow through with all vaccinations (ex. Getting all 3 doses of HPV or getting influenza vaccine yearly) Referrals from parents who previously opposed to vaccinating children. |

Reduce the transmission of preventable diseases (ex. Measles, influenza).

|

Causal hypothesis

Parents of children may choose not to vaccinate their children for a number of reasons. They make lack the knowledge of how vital vaccinations can be and the how easy it is for an unvaccinated child to infect others. Others may have prior knowledge of vaccinations, but may not be up to date or they may support invalid information. For many parents, they could also have a fear of physical or even social problems that may arise after vaccinating their child. There are also instances where parents have limited access or health care/services.

- Improving parents attitude toward vaccinations will increase their likelihood of participating in vaccination programs in schools and child care facilities.

- Decreasing/removing social or religious stigmas against vaccinating children will increase immunization rates in schools and child care facilities.

- Increasing/promoting perceived behavioral control among parents of school children will increase follow up in vaccinations that require multiple doses.

Intervention hypothesis

Information sessions about the vaccination program being conducted in the schools will lead to an increase in the number of parental consents that are collected. Multiple sessions will be held and will cater to the communities specific needs and interests. Trained staff and professionals will administer the information sessions and will provide information about the importance of vaccinating school children through slides and pamphlets. During these sessions parents will be able to ask questions and address any concerns they may have.

Meeting with leaders of communities and religious groups will lead to improvements in the way the community views childhood vaccinations. Program coordinators can offer supplemental material and even provide lectures to the community . They can work with the community to address any stigmas and find ways to reduce them.

Requiring parental consent in order to participate in the clinic will lead to greater perceived behavioral control among parents of school children. Making sure parents have the option of participating in the clinics will make them feel like they have more control over the situation.

SMART Objectives

- Change parents attitude of vaccinations to be more positive

- Outcome objective: By the end of May 2017, the number of parents whose attitudes about child vaccinations changed from negative to positive will increase by 35%.

- No social stigma against vaccinating children.

- Outcome objective: The number of parents who view childhood vaccinations as a socially acceptable task will increase by 15% by the end of May 2017.

- Greater perceived behavioral control among parents of school children.

- Outcome objective: There will be a 40% increase in the number of parental consents collected from the first clinic to the fourth clinic by the end of May 2017 for students who have had no prior vaccinations.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

Table 4. Role of Stakeholders in the Intervention program

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Parents of school children | Give permission for children to participate in the intervention | What are the risks/complications that can arise from vaccinating my child? Will the program cost us, if so how much? What are the consequences for not vaccinating my child? |

If program is successful, parents will continue to vaccinate their child as they get older.

Also, they will promote the intervention program to their peers, family and communities. |

If program is unsuccessful, parents will be not promote the intervention program and will continue to have negative attitudes toward vaccinations. |

| School children | Who the intervention is being provided to | How many shots will I be required to get? | School children will continue to get vaccinations as they get older. | School children will not get vaccinations. |

| School officials | Oversee all the details of the program and can serve as a middleman between program officials and parents | How do we deliver the program objectives to the parents of the students? How do we address parents who oppose of the intervention program? |

If successful, school officials may be open to experimenting with other intervention programs that pertain to school children. Also, schools will continue to implement the program in the future. |

School officials will not be likely to participate in future intervention programs if this one is unsuccessful. |

| Politicians from local and state governments

Program staff and volunteers |

Provide funding for the program

Administer the intervention program |

How much money is required to implement this vaccination program? Will this program be easy to replicate in other schools and at a low cost?How many participants will there be by the end of the program?How do we convey our goals and objectives to the community?How to make program run smoothly with little problems and complications?What to do if complications arise? |

If program is successful, politicians can make laws to implement these programs in other schools. Also researchers from this program can get more funding to expand their program and conduct more research about vaccinating school children and parental influenceIf program is successful, they can offer it at other schools and it could become a national program. |

If program is costly and ineffective, politicians will most likely allocate funding to other related programs.

If program is unsuccessful, program staff may have a harder time advancing their research and promoting the intervention.

Will get less funding and support for the program.

|

Study Design

Outcome evaluation design: Quasi experimental study design with a non-random comparison group

Scientific notation

O X O (parents who allow their child to be vaccinated)

O X O (parent who do not allow their child to be vaccinated)

Studies would be conducted each of the following locations;

- Child care facility

- Elementary school (k-5)

- Middle school (6-8)

- High school (9-12)

Schools and child care facility will be chosen at random from one specific county.

Threats to Internal Validity

Bias and confounding are potential threats to the internal validity of the evaluation.

Selection bias may occur when choosing schools to participate in the program. Schools in the same county can vary depending on location as well as the communities that inhabit the area. There might be more of one race in the area and socioeconomic classes can vary depending on the region. This could affect the results of the program and in turn this type of study not generalizable to other schools in different counties. In order to reduce selection bias, schools will be randomly selected.

Information bias may occur depending on where the programs are being held. Staff may have to approach young children differently than they would older children. Having a consistent protocol that is sufficient at all locations is crucial.

While this study will take into account confounding factors like socioeconomic status and race, there may be other factors that are not as apparent and may have an confounding effect. Controlling for these factors during data analysis will help show the true relationship between the intervention program and outcome of interest.

Table 5. Assessing the Reliability and Validity of the Short- term outcomes

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Change parents attitudes about vaccinating children | Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines survey (PACV) to measure vaccine hesitancy

Opel et al. 2013 |

PACV is a survey that is used to identify vaccine hesitant parents. It is a 15 question paper survey that encompassess 3 domans; behavior, safety and efficacy, and general attitudes. | Score for PACV is a scale 0 to 100

With 100 meaning high vaccine hesitancy “Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy? |

Predictive validity Parents with higher PACV scores had children who had higher percentage of days underimmunized. Test-rest reliability “mean PACV score for the test-retest respondents was 23.8 at baseline and 21.9 at 8 weeks” |

| Making childhood vaccinations a socially acceptable tasks among communities* | Mailed Survey that included questions about mother’s attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control toward the HPV vaccination for their daughter.

Askelson et al. 2010 |

Survey was used to measure the constructs of the theory of planned behavior, mothers experience with STIs, mothers opinions on child’s risk of HPV and vaccine itself | Attitude

“ Vaccinating “is necessary,” “is a good idea,” and “is beneficial” Likert scale question “The people in my life whose opinions I value would want me to vaccinate my daughter.” “It is mostly up to me whether or not my daughter gets vaccinated against HPV.” Likert scale question “My daughter is or will be at risk for HPV” |

Reliability AttitudeCronbach’s alpha = 0.96 Subjective normCronbach’s alpha = 0.88Perceived behavioral control Cronbach’s alpha = 0.38 Validity AttitudeEx. vaccinating is a good ideaFactor loading=0.98 Subjective normEx. most people think i should vaccinate my daughter.Factor loading=0.94 |

| Greater parental perceived behavioral control* | Online survey, that included questions about health status, sexual health, intention to get HPV vaccination, how they use the Internet to assess health concerns

Survey was emailed to staff and students of a university Britt et al. 2014 |

Survey was conducted to see the effect the interaction between perceived behavioral control and the other constructs of the Theory of Planned behavior had on the intended behavior

(getting HPV vaccination) as well as the association perceived behavior control has with “potential recipients retrieving, understanding, and using online information with regard to the vaccine” |

Survey Questions: Behavioral Intent“I intend to get/complete the HPV vaccine in the next year,” Attitude“Getting/completing the HPV vaccination over the next year would be … ” Likert Scale questions: Subjective Norm’Most people who are important to me think that I should get the HPV vaccination” Perceived behavioral control“It is mostly up to me if get/complete the HPV vaccination in the next year.” |

Reliability Attitude:Cronbach’s alpha = .93 Subjective norm: Cronbach’s alpha = .91 Perceived behavior control: Cronbach’s alpha = .90 |

*surveys were not administered in school settings, and if they were to used for this program they would modified.

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Recruitment/Enrollment Forms

Information Session Invitation

Email will sent to all the parents of children in the school. For parents whose email is not a file materials will be mailed.

Dear Parents,

Your school has been selected to participate in a childhood vaccination program. This program is focused on increasing immunization rates among children by promoting the benefits of vaccinations. During the school year, multiple vaccination clinics will be held at the school. Information session will be held to describe the program as well as include discussions on the importance of the vaccinations provided in the United States. You will have the opportunity to ask questions and address your concerns at the sessions. After attending the session, you as the parent will have the option of allowing your child/children to participate in the clinics.

Please indicate whether you plan to attend the information session or not by using the following link.

www.linktoinvitationforinformationsession.com (will have yes/no, maybe options to mutiple session times and dates)

| What the link will lead to: RSVP to information session

If you indicated yes, please select times that would be convenient for you to attend a session. Session Date Time 1. 2. 3. 4. |

Attached is information about the program as well as information about what vaccinations that will be offered during the clinics.

Thank you for your time and we look forward to seeing you at one of our information sessions. If you have any questions, please contact us by email or by phone.

Sincerely,

Program Coordinator

Vaccination Clinic Form

After parents attend information they will receive a secondary email to ask whether they chose to participate in vaccination clinic or not.

Dear Parents,

Our records indicate you have attended an information session.

If you intend on participating in the vaccinations clinic please RSVP by using the link below. Details regarding the clinics are listed below.

RSVP link to clinic

For those who have chosen not to participate, if you could take a few minutes and fill out the linked feedback form to let us know why you made your decision and things we could do differently that would be greatly appreciated.

Link to feedback form

Vaccination clinics will be held after school and appointment times will be emailed. Fill out the attached forms which include medical history as well as which vaccines your child intends on getting and bring them during your appointment. Also, if your child has been previously vaccinated, please bring a copy of their immunization records.

Thank you again for your time and participation. Let us know if you have any questions.

Sincerely,

Program coordinator

Attrition Forms

Sign in sheet at information session

| Parent name | Contact Information (phone and/or email address) | Did you receive the email regarding this information session? | Did you receive a pamphlet? |

Sign in sheet at vaccination clinic

| Parent name | Child name | Contact Information (phone and/or email address) | Did you attend an information session? |

Fidelity Forms

| Parent name | RSVP to session | Attended Session | RSVP to clinic | Attended Clinic |

Feedback form given to all parents

Dear Participant,

If you attended both information session and the vaccination clinic, please answer questions for both sections. If you only attended one, only answer questions to that specific section.

Information Session

Was the session informative? Yes No

Were you able to address your concerns? Yes No

Were program staff able to answer your questions? Yes No

Prior to session, were you skeptical of vaccinating your child? Yes No

Did the session influence your decision to vaccinate your child? Yes No

List changes that could improve the session.

_____________________________________

Vaccination clinic

Why did you chose to vaccinate your child? ______________________.

Did you child have prior vaccinations? Yes No

Would you recommend this program to other families? Yes No

If there is any changes you would recommend for future clinics, please write below?

__________________________

Forms to be filled out by program staff and/or coordinators

Form used to track timing of sessions

| Time Start | Time End | |

| Session #1 | ||

| Session #2 | ||

| Session #3 | ||

| Session #4 |

Please check the topics that were covered during each session.

| Topics | Session # 1 | Session #2 | Session #3 | Session #4 |

| Why vaccinate child? | ||||

| Consequences of not vaccinating child | ||||

| What vaccinations are recommended? | ||||

| Pros to vaccinations | ||||

| Autism and vaccines | ||||

| Questions from audience |

For each session please indicate which topic was discussed the most and which topic was discussed the least.

| Session | Most covered topic | Least covered topic |

| #1 | ||

| #2 | ||

| #3 | ||

| #4 |

Feedback form from program staff

Which topics did you find necessary/useful? _______________

Which topics would you recommend shortening or removing from presentation?__________

Did the sessions run on-time, overtime, or under-time? Circle one

Were the presentations too long or too short?________

Did the presenter do a good job presenting the information? Yes or No

If no, please specify why. ________

What are some changes you recommend for the program? ________________

References

Daley, M. F., Kempe, A., Pyrzanowski, J., Vogt, T. M., Dickinson, L. M., Kile, D., . . . Shlay, J. C. (2014). School-Located Vaccination of Adolescents With Insurance Billing: Cost, Reimbursement, and Vaccination Outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3), 282-288. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.011

Britt, R. K., Hatten, K. N., & Chappuis, S. O. (2014). Perceived behavioral control, intention to get vaccinated, and usage of online information about the human papillomavirus vaccine. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 52-65. doi:10.1080/21642850.2013.869175

Glanz, K. (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda? Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Cancer Institute.

Mckee, C., & Bohannon, K. (2016). Exploring the Reasons Behind Parental Refusal of Vaccines. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 21(2), 104-109. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.104

Opel, D. J., Taylor, J. A., Zhou, C., Catz, S., Myaing, M., & Mangione-Smith, R. (2013). The Relationship Between Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines Survey Scores and Future Child Immunization Status. JAMA Pediatrics JAMA Pediatr, 167(11), 1065. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2483

Ridenhour, B. J., Braun, A., Teyrasse, T., & Goldsman, D. (2011). Controlling the Spread of Disease in Schools. PLoS ONE, 6(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029640

Stubbs, B. W., Panozzo, C. A., Moss, J. L., Reiter, P. L., Whitesell, D. H., & Brewer, N. T. (2014). Evaluation of an Intervention Providing HPV Vaccine in Schools. Am J Hlth Behav American Journal of Health Behavior, 38(1), 92-102. doi:10.5993/ajhb.38.1.10

Yang, Y. T., Delamater, P. L., Leslie, T. F., & Mello, M. M. (2016). Sociodemographic Predictors of Vaccination Exemptions on the Basis of Personal Belief in California. Am J Public Health American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 172-177. doi:10.2105/ajph.2015.302926